Turkey referendum: The ultranationalists who could sway Erdogan vote

- Published

Meral Aksener is long known for her strong stance against Kurdish militants

"They all talk about Mr Erdogan. What if I am the country's next president?" Meral Aksener asks.

A former interior minister and a high-profile name in Turkish politics for over two decades, 60-year-old Ms Aksener has now emerged as one of the leading figures of the No campaign in Turkey's upcoming referendum and a possible challenger to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

In Turkey's closely-contested 16 April referendum, voters will decide whether to change the constitution to establish a presidential system and grant the president further executive powers.

Meral Aksener's far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) may be the smallest party in parliament but it may also hold the key to the president's ambitions.

Meral Aksener attracts large numbers to her rallies but several have been banned or cancelled

"In the parliamentary system you have checks and balances. Here you have no such thing," says Ms Aksener of the proposed changes.

"This is out-dated. This is a monstrosity. Anyone who has such powers would go crazy. I definitely would if it was me."

What will a Yes-vote mean?

Role of prime minister would be scrapped and president made head of Turkey's executive as well as head of state

President would be allowed to retain ties to a political party - not currently the case

President would have new powers to appoint ministers, prepare budget and enact certain laws by decree

President alone would have power to dismiss parliament and to announce state of emergency

New post of vice president would be created

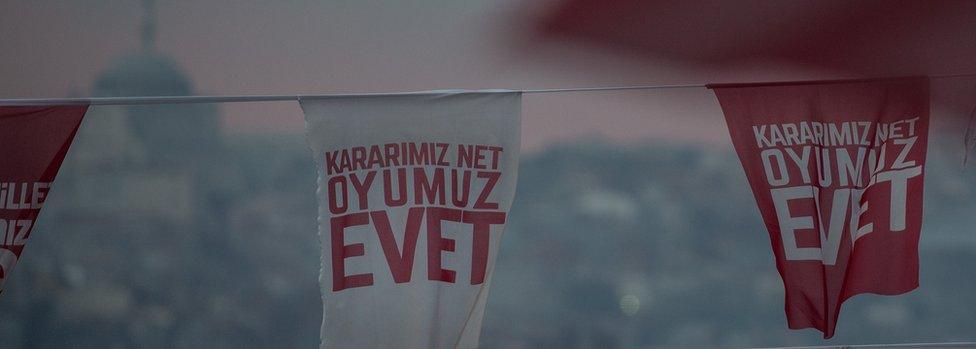

A big Yes campaign is in full swing in Turkey: here flags with the word Yes (Evet) are shown in front of an Istanbul skyline

The ultranationalists may have received only 12% of the vote at the last general election, but it was their unexpected support for Mr Erdogan and his ruling AK party that paved the way for the referendum.

The MHP has since split. While the leadership campaigns for a Yes vote, others in the MHP back the No campaign, and many of their voters are undecided.

Tensions have spilled over in party ranks and Meral Aksener herself has been ejected from the MHP for challenging the leadership but still has grassroots support.

Several of her rallies have been banned or cancelled and another leading opposition figure, Sinan Ogan, came under attack when a man knocked down the lectern from which he was giving a speech.

It was Mr Ogan, not the attacker, who was thrown out of the party.

Both he and Ms Aksener are adamant that they could sway around 80% of nationalist voters towards a No vote.

But MHP deputy chairman Erkan Akcay disagrees. "Within 10-15 years the whole of Europe will see how successful this presidential model is and will try to adapt accordingly," he argues.

Recent polls suggest the race could be very tight.

That, according to Meral Aksener, is why a row blew up between Turkey and several European countries.

First President Erdogan accused the German government of "reverting to Nazi practices" when Turkish ministers were prevented from addressing campaign rallies.

Then Dutch riot police clashed with Turkish protesters in Rotterdam, as police escorted a Turkish minister out of the country.

Ms Aksener argues that the government provoked tensions abroad because attempts to antagonise the secular opposition in Turkey had failed.

"The government decided to build a mosque in Taksim Square (in central Istanbul). They expected a riot. Nothing happened. The headscarf ban in the army was lifted. Nothing happened. So they escalated a tension with first Germany, and then the Netherlands."

"In foreign policy, you should think before you speak. If you make foreign politics a tool for domestic politics, our country loses in the end. The nation has seen through this. I do not think the latest crisis will drive a Yes vote."

President Erdogan's presence is dominant across Turkish media as he pushes for a Yes vote

As the date of the referendum approaches, Turks are holding their breath. Few votes in Turkey have been quite so unpredictable in recent years.

The government-led Yes campaign is trying to win over undecided voters with big advertising drive billboards and national media.

President Erdogan appears on TV every day, drumming up support for a constitutional change that he says is necessary for the country's stability.

The No campaign, meanwhile, is struggling to get its message across, complaining of an unbalanced media and of rallies being banned by local authorities. Nearly a dozen pro-Kurdish opposition MPs have been jailed.

Meral Aksener does not even want to consider defeat. "No matter what it costs me, I will be working towards a No."

- Published27 March 2017

- Published16 April 2017