UK faces tough divorce from the EU

- Published

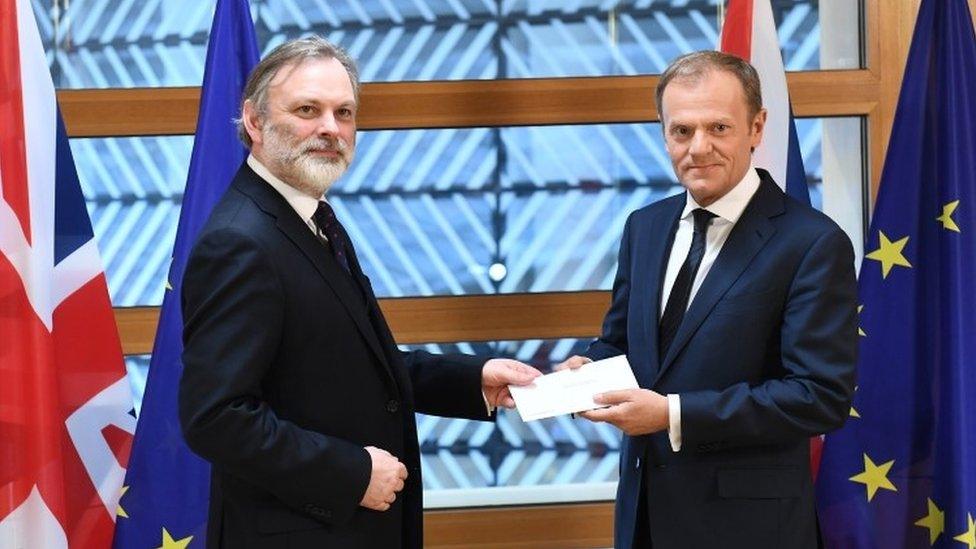

It is clear that the UK will face a tough divorce from the European Union after European Council President Donald Tusk characterised the forthcoming talks as "difficult, complex" and possibly "confrontational".

From the outset it is clear that the EU side will control the agenda.

That was underlined again on Friday in an early skirmish over procedure. Theresa May wanted divorce talks to run in parallel with negotiations about a future trading relationship. That won't happen.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel had been quick to rule that out and was given swift backing by the French president Francois Hollande. That was reinforced again on Friday with the leak of the European Council's negotiating guidelines.

Why is this so important?

Europe's leaders want to ensure that Britain agrees to the principles governing the terms of Brexit as a condition for talks continuing. As Mr Tusk said, the UK cannot just walk away without paying debts.

Angela Merkel insists the principles of Brexit should be negotiated before a trade deal with the UK can be considered

On the EU side there is another calculation: it will be easier to ensure unity among the 27 member states on the terms of the divorce, rather than on trade, when different national interests could come into play.

Preserving unity is a fundamental concern and Mr Tusk insisted that the EU "will act as one".

By insisting that the principles of the divorce bill be settled first, the leaders of the 27 are also stopping Mrs May using payments as a bargaining chip over the future trading relationship.

There were, however, some hints at flexibility, with Mr Tusk saying that the EU would monitor the negotiations and determine when "sufficient progress had been achieved to allow talks to proceed to the next phase of a future relationship".

Of course, it is the EU that will decide what progress has been made but those negotiations on trade could begin as early as the autumn.

For the EU there are four priorities in the talks: settling the divorce bill which some in Brussels have estimated at €60bn (£50bn), establishing the future status of EU citizens living in the UK, keeping open Northern Ireland's borders and agreeing which laws companies will operate under post-Brexit.

But EU leaders have opened the door to holding trade talks before Brexit has been completed and some in the UK will see that as a promising gesture.

The negotiating guidelines allow for a transition period before a future trading agreement is in place. In Brussels there is an expectation that some kind of transition period will be needed after the divorce talks have been completed.

A trade deal can only be formally concluded once the UK has ended its membership.

EU leaders are expected to finalise the union's negotiating position on 29 April

The EU sees that transitional period as being "limited" and will insist that the UK continues to abide by Union rules during this period. That could prove very controversial because it means there is a very real prospect that, come the next UK general election in 2020, some payments to the EU are still being made with a continuing role for the European Court.

There are differences among Europe's leaders over how constructive they are willing to be in the talks. Some want to demonstrate that leaving the EU is not easy, that divorce must hurt.

The French believe there must be an element of pain to deter others, although the prospect of other countries leaving is currently very remote. Mr Tusk's perspective is that the process of leaving is "punitive" enough without further punishment being necessary.

Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson said on Friday that in calls he had made over the past two days there had been "lots of goodwill' from European Union ministers.

Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson has emphasised the "goodwill" shown by other EU members

The wider reaction is that the UK, by triggering Article 50, has stepped into the unknown and taken a huge risk. "A highly indebted Britain has most to lose from uncertainty," was one assessment.

The mood in the European press has been generally gloomy, seeing departure as an act of self-harm, of Britain being tied up in Kafkaesque procedures, of British citizens being worse off by €5,000 (£4,300) a year.

Some papers focused on the UK's future isolation, repeating what passes for accepted wisdom in Brussels that in a global world countries are better off in larger blocs. Among some commentators there was the scarcely veiled hope that at some stage the UK will return to the European fold, tail between legs.

The British strategy is to be constructive towards the EU project and to deliver on the "sincere co-operation" it has promised Angela Merkel.

It has accepted that some payments will have to be made to meet existing obligations, that EU citizens will have to retain rights during the negotiating period and that there may be some limited role for the EU's courts in settling trade disputes.

Theresa May will have to balance her room for manoeuvre with the demands of her own party

The UK has some cards: it can offer help with security and intelligence but, by tying that assistance to the future trading relationship, it prompted German MPs to cry "blackmail". Mr Johnson responded by saying that Britain's commitment to EU defence was "unconditional".

But it is clear that every time the UK tries to play its cards there will be voices, particularly from the European Parliament, in full complaint. Mrs May and her team will have to handle the parliament with great skill, as it will have a say on any eventual deal.

Europe will be on alert for any attempt by Britain to divide and rule the remaining 27 EU countries. Mrs Merkel has set out the German interest: despite intensive lobbying from German car manufacturers it is the unity and integrity of the European Union that will be the priority - the EU must not be damaged or weakened by these negotiations.

These guidelines will be fleshed out into a more comprehensive negotiating document that will be presented to Europe's leaders at the end of April.

Mrs May knows compromises will have to be made to avoid the talks breaking down, but her room for manoeuvre is limited by sections of her own party who are determined to ensure a clean break with the EU.

- Published31 March 2017

- Published29 April 2017

- Published29 March 2017

- Published30 March 2017

- Published30 March 2017