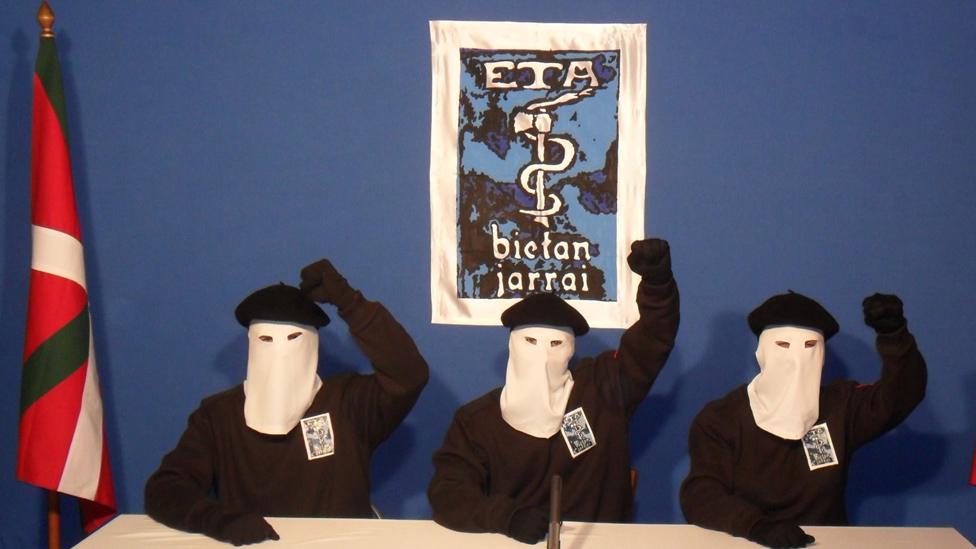

Eta: Basque separatists begin weapons handover

- Published

French police have begun opening the weapons caches listed by Eta

Basque militant group Eta has begun handing over its remaining weapons, ending the last insurgency in Western Europe.

At a ceremony in the southern French city of Bayonne, an inventory of weapons, and their locations, was passed to the judicial authorities.

French Interior Minister Matthias Fekl hailed the move as a "major step".

Eta killed more than 800 people in some 40 years of violence as it sought to carve out an independent country straddling Spain and France.

It declared a ceasefire in 2011 but did not disarm.

Mr Fekl said the inventory included eight sites, and a police operation was under way to secure them.

The caches contain 120 firearms, three tonnes of explosives and several thousand rounds of ammunition, according to a spokesman for the group which mediated between Eta and the French authorities.

What is Eta?

The group was set up more than 50 years ago in the era of Spanish dictator General Franco.

Its goal was to create an independent Basque state out of territory in south-west France and northern Spain.

Its first known killing was in 1968, when a secret police chief was shot dead in the Basque city of San Sebastian.

France and Spain refuse to negotiate with Eta, which is on the EU blacklist of terrorist organisations.

It has taken years to convince Eta members to disarm without getting anything in return, says the BBC's Lyse Doucet, in Bayonne.

She says she has been told about 100 hardline fighters still oppose the move.

Eta killed hundreds of people over 40 years

How can we be sure Eta has really given up its weapons?

French police have begun checking the list of sites handed over on Saturday.

There is also the International Verification Commission (IVC), set up in 2011 to monitor Eta's progress towards disarmament.

It is not recognised by the French and Spanish governments, but it does have the backing of the regional Basque government in Spain.

In 2014, the IVC reported that Eta had taken some of its weapons out of action, but the Spanish government dismissed the move as "theatrical".

The Spanish government does not believe Eta will hand over all its weapons, Reuters quoted a government source as saying.

How did we get here?

Slowly, and with many false starts.

Eta's first ceasefire was in 1998, but collapsed the following year.

In 2006, it made another pledge to lay down arms that, too, proved to be illusory. In December of that year, it bombed an airport car park in Madrid, killing two people.

Four years later, in 2010, Eta announced it would not carry out further attacks and in January 2011, it declared a permanent and "internationally verifiable" ceasefire but refused to disarm.

In recent years, police in France and Spain have put Eta under severe pressure, arresting hundreds of militants, including leadership figures, and seizing many of its weapons.

Eta's political wing, Herri Batasuna, was banned by the Spanish government, which argued that the two groups were inextricably linked.

'A moment we have been waiting for' - the BBC's Lyse Doucet in Bayonne

A simple ceremony in a city hall ended Eta's bloody campaign for independence. In an elegant high-ceilinged room, five people sat around a plain square table as early-morning light filtered through heavy drapes.

Bayonne Mayor Jean-Rene Etchegaray welcomed them to a "moment we have all been waiting for". After a few short speeches, French Basque environmentalist Txetx Etcheverry approached the table with a bulky black file, with a dozen blue folders. From where I sat, I could see it included photographs as well as text.

The dossier was handed to international witnesses including Italian Archbishop Matteo Zuppi and the Reverend Harold Good, who played a role in the Northern Ireland peace process. French security forces discreetly secured the area and the Spanish government raised no objections to the ceremony going ahead.

Ram Manikkalingam of the IVC called it a "new model of disarmament and verification which emerged from Basque society".

- Published7 April 2017

- Published16 May 2019

- Published17 March 2017

- Published8 April 2017

- Published17 December 2016

- Published21 February 2014

- Published6 September 2010