France's tight presidential race hinges on volatile voters

- Published

Emmanuel Macron has the edge in the latest poll but the race is too tight to call

The end of the first round of the French presidential election is in sight and the candidates have almost run out of time to appeal to the voters. But the voters, it seems, have not run out of surprises for the candidates.

The latest opinion poll for French TV suggests the race remains tight as Sunday's vote approaches.

Independent centrist Emmanuel Macron - the man who came from nowhere to lead his own, new, political movement into the campaign is still ahead of Marine Le Pen of the National Front. But only just.

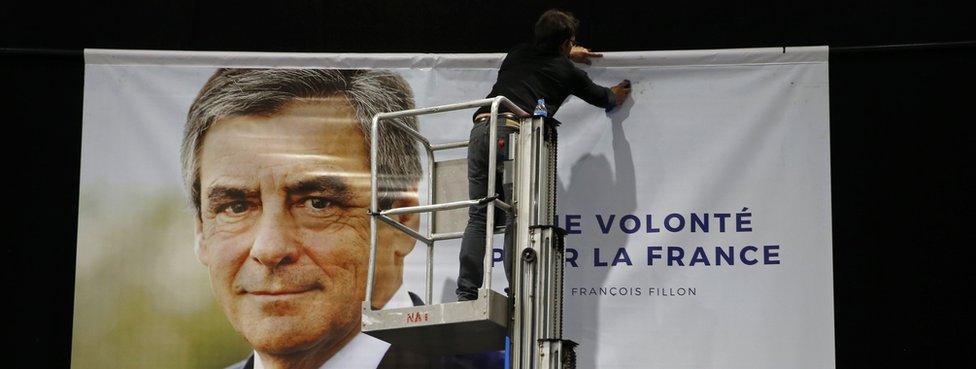

A little further back comes François Fillon, the traditional conservative whose run for the presidency has been tainted by allegations of financial corruption, and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the veteran leftist enjoying an extraordinary resurgence.

But the most striking feature of the late opinion polls isn't the tightening of the race, as the two front-runners both drop a couple of points in the rankings.

It is the sheer volatility of the electorate.

A quarter of those who intend to vote say they may change their minds about who they vote for between now and Sunday. When you consider the huge ideological and cultural differences between, say, Macron and Mélenchon or Fillon and Le Pen that's a remarkable statistic.

The four front-runners are (L-R): François Fillon, Marine Le Pen, Emmanuel Macron and Jean-Luc Mélenchon

The candidates have one final chance to take advantage of that volatile mood - a television event on Thursday night which is more likely to test the voters' stamina rather than fray the nerves.

National Front leader Marine Le Pen is widely expected to qualify for the second round run-off

The format is not confrontational but involves a series of interviews of around 15 minutes which will include an opportunity for each candidate to rebut charges made against them by the others. It all threatens to lack drama but it is also a genuine last chance for the voters to judge the politicians who aspire to lead them.

French elections, though, are not decided on television. At least not entirely.

Public meetings still matter enormously here, and in the north-western city of Nantes there is plenty of energy in the campaign - even in the last few exhausted days of the first round.

Both Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Emmanuel Macron managed to fill the 7,000 seater Zenith Centre on the edge of the city on consecutive days.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon appeared in seven places at once

Mr Macron came in person while Mr Mélenchon appeared in a hologram projected from Dijon, which also appeared at the same time as far away as the city of Le Port, on the Indian Ocean island of La Réunion.

That anecdotal evidence of a high level of engagement sits oddly with national polling that suggests fewer people intend to vote in the first round of 2017 than voted at the same stage of the election in 2012.

But at the Macron rally I met one voter whose views helped to explain the underlying volatility of the vote.

When I asked him why he supported Macron he corrected me.

"I'm telling you that Macron is someone to whom I've listened, someone I want to see as president of France now but I am not a political supporter of his," he told me.

Centre-right candidate François Fillon has been hit by a "fake jobs" inquiry but is still in the race

"I am a voter. My choice has been made. I don't consider myself a supporter but as far as I am concerned it can't be anyone else as president of France."

That rather nuanced decision, that Emmanuel Macron is the best of the current slate of candidates although not necessarily a fixed political choice for the future, reflects a mood of readiness among French voters to pick a candidate who meets the circumstances of the moment but who certainly cannot count on a lifetime of political loyalty.

The best bet for the second round is that it will see Marine Le Pen face off against either Emmanuel Macron, Jean-Luc Mélenchon or François Fillon, with the centrist at the moment the likeliest of those three to win through.

But there is that final examination on TV still to come and there is still that underlying volatility in the vote. A maddeningly unpredictable race remains unpredictable to the end.

- Published24 April 2017

- Published3 May 2017