French election 2017: Why is it important?

- Published

The old model of French politics has been shattered by the first-round result

France's voters have rejected the two big political parties that have governed for decades and are now at a crossroads as they choose a president.

Will they go for a pro-European liberal who has never before been elected, or a far-right challenger to the establishment, who has vowed to take on globalisation and France's relationship with the EU?

After the Brexit vote in the UK and the election of US President Donald Trump, France is the latest country to deal a blow to politics as usual.

What is new about this election?

The Socialists and the centre right have run France since the 1950s, but the old model has been shattered.

An unpopular and divided ruling Socialist party and a Republican candidate in the crosshairs of judicial inquiry have cleared the way for a president who has never been elected to the French National Assembly.

Marine Le Pen's party already has a strong showing in the European parliament

Whoever wins, centrist Emmanuel Macron or populist Marine Le Pen, France will have a president with an agenda for change.

The far right already runs eight towns and has 20 MEPs in the European Parliament - but is widely shunned by the political mainstream.

Mr Macron's En Marche! (On the Move!) movement is an unknown quantity. Set up in April 2016 when he was economy minister, it has never before contested an election. And until now, nor has he.

What is at stake?

Voters will be making a decision on France's future direction and on its place at the heart of the European Union.

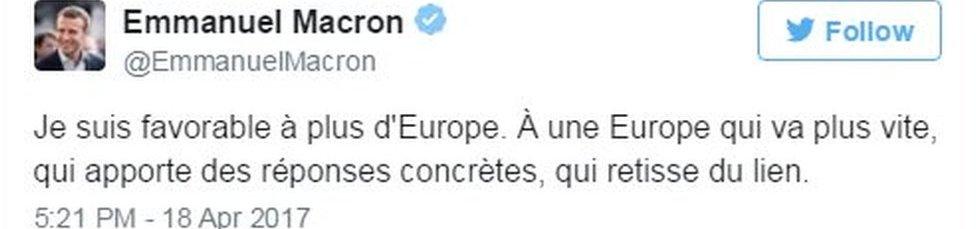

If they opt for Emmanuel Macron, they will be backing a candidate who seeks EU reform as well as deeper European integration, in the form of a eurozone budget and eurozone finance ministers.

"I'm in favour of more Europe. In a Europe that goes faster, delivers concrete responses and re-establishes the connection"

If instead they choose Marine Le Pen she promises quite the opposite. She wants a Europe of nations to replace the EU.

"I give myself six months to negotiate with the EU the return of sovereignty. Then it will be the French who decide," she tweeted.

The assumption is that she would fail and a referendum would take place initially on France's membership of the euro.

A poll in March suggested that, external seven out of 10 French voters were opposed to France pulling out of the EU, but Emmanuel Macron was the only candidate standing on a pro-EU platform in the first round of the presidential election.

Who will win?

All opinion polls suggest Mr Macron is heading for a big victory, polling about 60% in the second round - though his lead has narrowed in the last days before voting.

He's won once, can he do it again?

He defeated Marine Le Pen in the first round and few commentators believe she will turn the tables on 7 May.

Her best hope may be in voters failing to turn out in large numbers on the day.

A day after reaching the second round, Ms Le Pen stepped down as leader of the National Front, which she has led since 2011, to concentrate on the presidential race.

The move is an apparent bid to broaden her appeal by creating artificial distance between her run for power and her party's hard-line policies.

Will a new president spell the end of old politics?

Quite possibly not. Because Emmanuel Macron has no MPs, and Marine Le Pen has only two.

So to have any power to push through their proposals the next president will need their party to perform well in legislative elections on 11 and 18 June.

Barely was Mr Macron's first-round success known before he announced plans for a majority in the New Assembly, made up of "new faces and new talents". Half of his candidates will be women - but his problem will be that none will be household names.

So for both the shadow of cohabitation looms, in which parliament is under the control of another party. It raises the prospect of governing with the help of politicians from other parties.

What are the battleground issues?

One of the overriding issues facing French voters is unemployment, which stands at almost 10% and is the eighth highest among the 28 EU member states. One in four under-25s is unemployed.

The French economy has made a slow recovery from the 2008 financial crisis and all the leading candidates say deep changes are needed.

Economic challenges facing next president

Marine Le Pen wants the pension age cut to 60 and to "renationalise French debt", which she argues is largely held by foreigners.

Emmanuel Macron wants to cut 120,000 public-sector jobs, reduce public spending by €60bn (£50bn; $65bn), plough billions into investment and reduce unemployment to below 7%.

What about security?

The election is taking place amid a state of emergency, and the first round took place three days after a policeman was shot dead on the Champs Elysées in the heart of Paris.

More than 230 people have died in terror attacks since January 2015 and officials fear more of the hundreds of young French Muslims who travelled to Syria and Iraq may return to commit new atrocities.

Dozens of people were killed in the Nice lorry attack on Bastille Day in 2016

Intelligence services believe attackers are deliberately pursuing a Le Pen victory, says the BBC's Hugh Schofield in Paris - because that could tip the country into chaos.

The former FN leader wants to suspend the EU's open-border agreement on France's frontiers and expel foreigners who are on the watch lists of intelligence services.

What makes the National Front far-right?

Ms Le Pen is fighting to appeal to the centre and left of French politics after working to move the party away from the image of her father, who has been repeatedly convicted for hate speech and describing the Holocaust as a "detail of history".

Why people are voting for Marine Le Pen

But she still has a far-right platform. She wants to allocate public services to French citizens ahead of foreigners. She also wants "automatic" expulsion of illegal immigrants and a moratorium on all legal immigration before cutting it to 10,000 per year.

She courted controversy again in the weeks running up to the election by suggesting that the French state was not responsible for rounding up Jews to send them to Nazi death camps during World War Two.

And the FN's links with Holocaust denial were highlighted once again when the man who replaced Ms Le Pen as its leader was himself forced out after only three days when he was accused of historical remarks underplaying Nazi atrocities.

The FN also has close ties with other European parties such as Austria's far-right Freedom Party - parties that mainstream right-wing parties want nothing to do with.

- Published24 April 2017

- Published24 April 2017

- Published24 April 2017

- Published24 April 2017

- Published25 April 2017