France election: Southern voters not writing off anyone

- Published

Locals in southern France say the election outcome is too close to call

To find out what French voters make of their forthcoming presidential election, I am following the route of the Tour de France and this week I have reached the south of the country.

In the bar of the betting shop at Salon-de-Provence, Michel is all smiles. A lucky flutter has left him €16 (£13.40) better off than when he first walked through the door. But when I ask him if he would care to place a bet on the outcome of the election, he stuffs the money firmly into his trouser pocket.

"These elections are the most rotten I've ever seen," he says.

"I don't know how to call this one. If I had to place a bet though I'd probably go for Macron. No wait. Maybe Marine. Marine Le Pen. I don't know. I really can't tell you."

Jean, who is not on a winning streak this morning, is hunched moodily over his coffee cup.

He tells me he will not waste a cent on the elections but when I push him he suggests that he might back "that outsider bloke from the hard left. The one who speaks well - Jean-Luc Mélenchon".

He is, though, keen to make me understand that he is not taken in by any of "that rubbish Mélenchon spouts forth".

The political analysts would agree with Michel and Jean that this election is just too close to call.

The four main candidates - centrist Emmanuel Macron, the far-right leader Marine Le Pen, the far-left's Jean-Luc Mélenchon and the right-wing Republican party's François Fillon, are all bunched fairly tightly together with only a few points to separate them.

The election result is unlikely to be found in Nostradamus's prophecies

If you are determined to forecast the result, then Salon-de-Provence is a good place to try - it was after all the home of the 16th Century doctor and astrologer Nostradamus who wrote his famous The Prophecies here.

His fans believe he predicted everything from the Great Fire of London to the two world wars and even the election of Donald Trump.

The curators at the Nostradamus Museum laugh when I tell them I have come to discover the result of the forthcoming elections.

"Nostradamus was a doctor," Lisa Laborie Barriere reminds me.

"He was not writing insights into the future but rather he was writing about possible things that could happen from the symptoms of society. But they are not precise so I'm afraid you won't find a clue to the election results here."

The far-left camp has been trying to win over people in Salon-de-Provence

In a hall on the outskirts of the town, Zembout Mehdi, a Mélenchon activist, is holding a public election debate and trying to win people over to his far-left camp.

He is certain Mélenchon will be in the second round and laughs when I say the polls suggest it will be Le Pen and Macron.

"You can't believe the polls," he sneers.

"They are controlled by French billionaires - the same guys who own the 24-hour news channels and they are all Macron supporters - so of course their polls favour their candidate over ours."

At the local bowling alley, Frederique and her friends are in fierce competition.

"Don't write off anyone too soon," one of them warns me as he prepares to throw.

"If I had to make a bet, I'd put money on Fillon bouncing back," he grins at me over his shoulder, "although I won't be voting for him."

Anna has worked at the fish market for 70 years and believes security is what matters most

In Marseille's Vieux Port at the early morning fish market, no-one is in jovial mood.

Earlier this week police announced they had foiled a terror plot here and had arrested two young men in France's second biggest city.

"Terror has become part of our daily life," says Dominique as she pours water over her sea bream. "Security will influence lots of people's votes because of not feeling safe.

"I'm not going to say how I will vote but lots of people here will vote National Front (FN) because they've had enough. We're obliged to vote FN because things have been left to drift too far," she adds.

"Security is what counts most, my darling," says 85-year-old Anna, raking through the prawns in her tray.

Soldiers have been patrolling streets since the attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices in 2015

Silently, slowly, small patrols of khaki-clad soldiers patrol Marseille's old harbour, gloved hands on their weapons, eyes hidden behind dark glasses.

The day after the attacks on the offices of the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo in January 2015, 10,000 soldiers were deployed across France to public areas such as stations and tourist sites as part of Operation Sentinelle.

Squadron Sergeant Matthieu admits he did not join the army to take part in domestic deployments but insists that he is proud to be part of this operation.

"We are on national territory protecting our national citizens. It's hardly an easy mission. You know what's been happening with terror attacks in France. It's true we could be a target ourselves so we have to be extra vigilant."

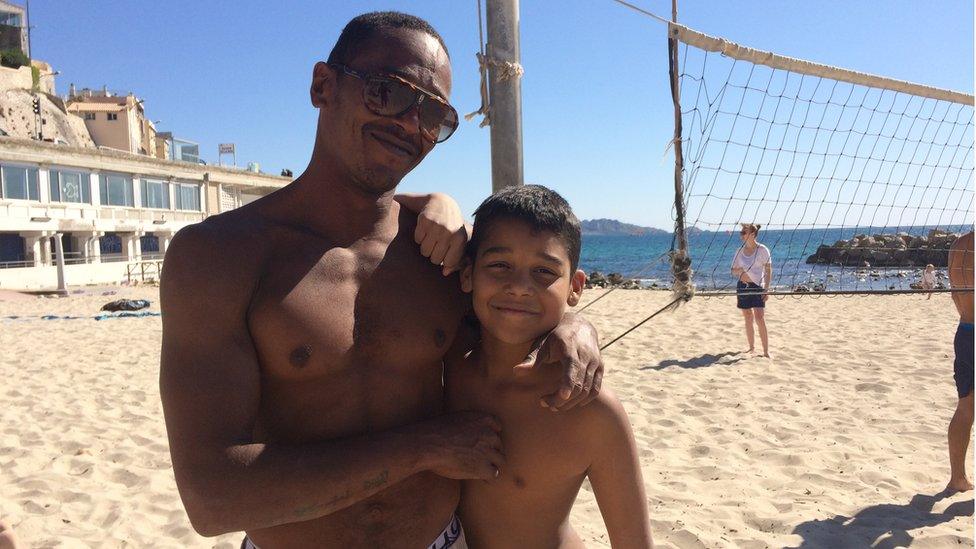

Jean-Claude believes the politician who is most vocal on security will have the best chance of winning

At the Prophete beach, the spring sun is battling against the still wintry wind to entice locals. Jean-Claude has come to play volleyball with his friends and young nephew.

"I'm worried about security," he admits stepping away from the court.

"I've just become a dad and it really frightens me now. I am sure the person who will win most votes in this election will be the person who's talked most about security."

In her office behind the Town Hall, deputy mayor Caroline Pozmentier-Sportich, the elected official in charge of public security, warns that the government needs to devolve some power to local authorities if cities and towns outside Paris are to remain safe.

"You have people in France who are identified as possible terrorists and the mayor of the city doesn't know who they are," she says. "It's very important now to give to the mayor and local police the power to fight with the state against terrorism."

Back at the beach, the biting wind is chasing the sun-seekers from the sand.

"For the first time in my life," says Marie, wrapping a fleece around her shoulders, "I'm scared. Really frightened. I think something really bad could happen here."

She pushes her sandy feet into plastic shoes and shivers.

"And I still don't know for whom I will be voting on Sunday."

You can listen to Emma Jane Kirby's full radio reports as she tours France on BBC Radio 4's PM programme.

- Published11 April 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published24 April 2017

- Published3 May 2017

- Published21 January 2017