French election: Why EU should not count its chickens on Macron

- Published

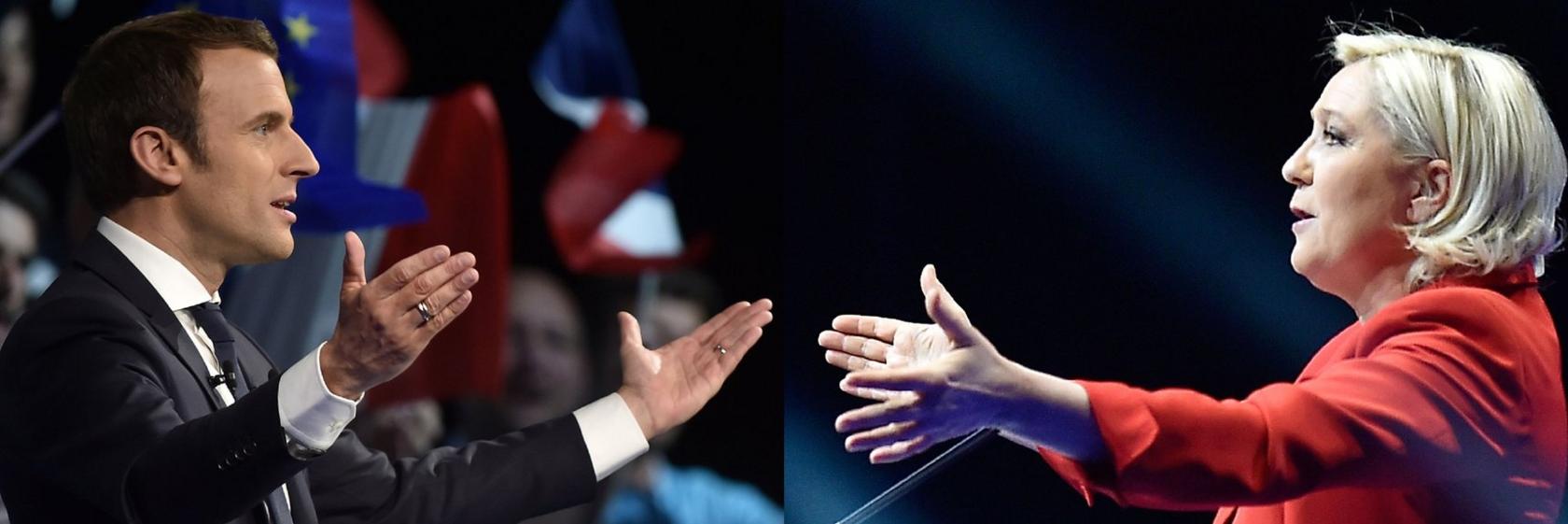

Emmanuel Macron is a passionate Europhile

The relief in Brussels is palpable. It believes it is (almost) back from the brink.

A passionate Europhile, Emmanuel Macron's presidential campaign is as much blue and yellow as it is the "tricolour" of France.

The EU, he believes, should to be at the heart of French politics, with more integration in finance, defence and migration.

He wants to breathe life into the now-spluttering Franco-German motor; to take a lead role with Germany to - in his eyes - Make Europe Great Again.

Angela Merkel and the European Commission's Jean-Claude Juncker can hardly conceal their delight. Both were quick to get on the phone to congratulate Mr Macron on his strong showing in Sunday's vote.

By this autumn fervent Eurocrats hope to look back fondly to a string of electoral defeats for populist Eurosceptics in Austria, the Netherlands, France, and then Germany.

But they shouldn't count their chickens.

Euroscepticism is widespread in France, whether or not Marine Le Pen becomes president.

Marine Le Pen tapped into anti-EU feeling

In the post-industrial north-east of France, with its hopelessly high unemployment, and in the resentful south-east with its struggling small businesses, globalisation and the EU are seen as joint public enemy number one.

The nostalgic nationalism peddled by Ms Le Pen is a source of comfort and hope.

"In the name of the people" is her campaign slogan. Woman of the people is her image.

Read more:

She was the only presidential candidate amongst 11 to hold their Sunday night election party outside Paris, basing herself in the troubled town of Hénin-Beaumont where she first made a political name for herself as a local councillor.

Sharpening her political claws against Emmanuel Macron, she is now keen to portray him as an arrogant elite-educated former banker, best friend of Brussels and the French bourgeoisie.

And if Ms Le Pen beats the odds and garners France's top political job, that would spell the end of the European project as we know it.

She wants France out of the euro - which so many French blame for high prices and uncompetitiveness.

And she dreams of the EU's demise, favouring a looser union of European nations over what she calls Brussels-domination.

The two will now go head-to-head in the second round

Post-Brexit Britain would then be high up on her list of preferred European partners.

But before that could happen, current Brexit negotiations and future trade talks would be left hanging as the EU slowly imploded.

There would be chaos across EU countries which would affect Britain too.

A President Macron, when it comes to Brexit, would likely play hardball.

He would help to keep the EU united in negotiations, making it harder for the UK to pick off individual countries, attempting to pressure or entice them to make a sweeter Brexit deal.

But EU passion aside, Mr Macron is not wedded to ideology. He is a newcomer to politics who claims to be neither right- nor left-wing.

During his meeting with Theresa May in February he said post-Brexit economic, defence and security co-operation with Britain must remain close.

As a former (if not long-standing) Minister of the Economy in France, he is unlikely to turn up his nose at a good trade deal with the UK.

- Published24 April 2017

- Published24 April 2017

- Published24 April 2017

- Published24 April 2017

- Published25 April 2017