French election: Five things we have learned

- Published

It was on the cards but still a shock: the two parties that have run France for nearly 60 years have lost power.

So what has the French presidential election told us that we did not already know?

1) You do not have to be mainstream to win

Marine Le Pen's far-right National Front has only two MPs and Emmanuel Macron's En Marche! (On the move) only emerged as a political movement in April 2016.

And yet one of these two politicians will be the president of France and between them they attracted almost half the vote.

Emmanuel Macron has never before been elected and now is favourite for the presidency

It is a new French revolution that leaves the centre-right Republicans and the Socialist left on the sidelines.

Yes, Mr Macron has served as economy minister in the outgoing Socialist government and was previously the president's protege. But he has never before been elected to a public position, and had to resign from the cabinet as his Socialist colleagues increasingly disowned him and his ideas.

2) The left is in ruins

We knew Socialist President François Hollande was unpopular but the party's candidate, Benoît Hamon, fell short even of his poll ratings, attracting just 6.35% of the vote.

And yet five years ago it was all so different, with electoral dominance in the National Assembly and Senate as well as the Elysée palace.

Not since 1969 has the left fared so poorly in France.

Benoît Hamon fared worse than any other Socialist since the 1960s

The seeds of this disaster were sown by the party's own public primary vote for choosing a candidate. A rebel in the party, Mr Hamon won the January vote convincingly, defeating the former prime minister, Manuel Valls.

But because he was a rebel he never had the complete backing of most of the cabinet. Mr Valls even sided with Emmanuel Macron. Voters deserted the party, largely for Mr Macron or far-left firebrand Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

3) Marine Le Pen: Winning votes but unlikely to win

Never before has the National Front (FN) attracted so many voters.

More than 7.6 million French voters backed Marine Le Pen. The last time her party came anywhere close to that number was in regional elections in 2015, with 6.8 million votes.

But the opinion polls do not augur well for her, even though arguably everything was in place for an optimal outcome.

Polls suggest Marine Le Pen is on course for less than 40% of the vote in the second round

The Le Pen team have fought for years to "detoxify" the FN brand; for years she was leading the opinion polls, her party won regional and European elections and the two mainstream parties were at a low ebb.

And yet she still lost ground to Emmanuel Macron as the vote approached.

A Harris Interactive poll suggests only 13% of voters believe she is likely to win on 7 May. Is that because her party is seen as a voice of protest, incapable of taking power?

4) Opinion polls are not always wrong

Recent experience from the Brexit referendum in the UK in June 2016 and the Donald Trump presidential victory in the US has told us to be wary of opinion polls and maybe not completely trust them.

People do not always tell pollsters what they really think and some have called into question the methodology used.

What does this mean for Brexit?

But the French election may have restored some faith in the polling organisations, which accurately predicted the decline in support for Marine Le Pen and the rise of Emmanuel Macron. It was only in the days before the vote that the polls showed him pulling ahead, and that was the result that emerged.

They also captured the rise of Jean-Luc Mélenchon - whose popularity swelled after his well-received performance in televised debates.

5) Scandals do not win elections

The centre right were favourites to win. Their candidate, François Fillon, was chosen in a popular vote and things were looking good.

But then came the bombshell allegations that his wife was paid public money for work she did not do and that he had a liking for expensive suits and watches.

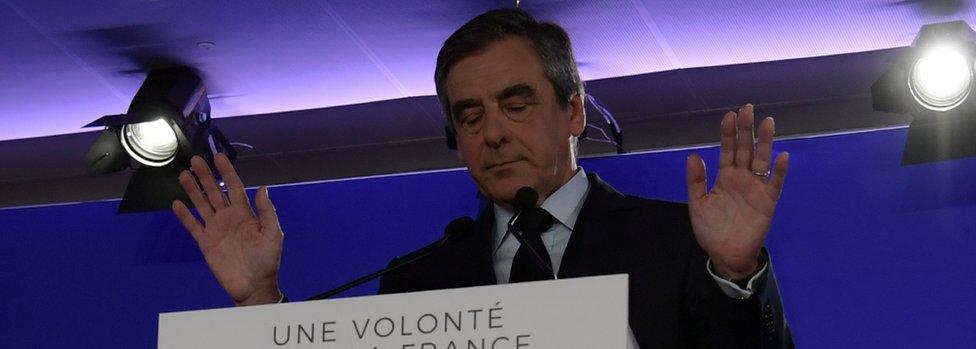

So maybe it was not such a good idea: François Fillon speaks to supporters on 24 April

The Republicans were caught in a slow-motion car crash but because Mr Fillon had won the primary there was no Plan B. And the only possible alternatives looked little better.

For a start, Mr Fillon refused to go. But veteran Alain Juppé was deemed no better because he had been banned from politics for a decade in an earlier party-funding scandal. And ex-President Nicolas Sarkozy has had his own problems with France's judiciary too.

In the end securing almost 20% of the vote was an achievement, but the Republicans never really stood a chance.

- Published3 May 2017