What does Marine Le Pen do now?

- Published

Marine Le Pen may have lost the election but she was filmed dancing away with her supporters shortly afterwards

"It's the people who decide," Marine Le Pen told me during the final days of the run-off campaign.

The people have now decided that they don't want her as their president. Ms Le Pen lost this election comprehensively. But at her campaign headquarters, she and her supporters chose to define success in a different way. The National Front is a movement which measures its progress over decades.

The party began in 1972 as a fringe, extremist group; for years, it was ignored or boycotted by much of the rest of the country. Its founder Jean-Marie Le Pen influenced the national debate, but was incapable of winning power.

In the 2002 presidential run-off, Mr Le Pen's progress was blocked by a so-called Republican Front - the decision by all mainstream parties to stick together and back Mr Le Pen's opponent, President Jacques Chirac.

Fifteen years on, Marine Le Pen has fractured the front, which once united against her father. In winning more than 30% of the run-off vote, she has taken a significant step towards her goal of making her movement respectable and electable.

Read more

In 2002, Jean-Marie Le Pen's opponents refused to appear on stage with him - for fear of legitimising him as a politician. In 2017, Marine Le Pen took part in debates, and came across as an accepted member of the political class.

Her run-off endorsement by a small party candidate - Nicolas Dupont-Aignan - gave her further legitimacy. But all this only took her so far in this election.

A new name?

Marine Le Pen may now try to broaden her party's approach. In her concession speech, she announced plans to form a new political movement, in alliance with Mr Dupont-Aignan and others.

She'll even re-name her party, on the assumption that the National Front's name is an obstacle to winning over more voters.

Ms Le Pen also insisted that hers was now the main opposition force in the country. That may be true in the very short term. France's mainstream right-wing and left-wing parties are still trying to work out how to recover from their respective first round defeats in this election.

But the far right politician faces serious problems ahead. Her widely criticised performance during the run-off debate calls into question her ability to win over a greater share of the electorate in the future.

Investigations into alleged financial misconduct relating to the way she runs her European parliamentary office may continue to cause her problems.

What's more, Marine Le Pen's party only has two MPs in the French National Assembly (out of a total membership of 577).

She'll have a chance to improve this in parliamentary elections in June. But it is a meagre base from which to build a true opposition force.

Does Ms Le Pen's niece want the National Front crown?

One of the party's two sitting MPs is her own niece, 27-year-old Marion Marechal-Le Pen.

Ms Marechal-Le Pen is increasingly popular within the party, and takes a more hardline position than her aunt. It's conceivable that the younger Le Pen may seek to make a future challenge for the leadership (for a movement which has its roots in the idea of a Republican France, the National Front continues to display quasi-dynastic/monarchical tendencies).

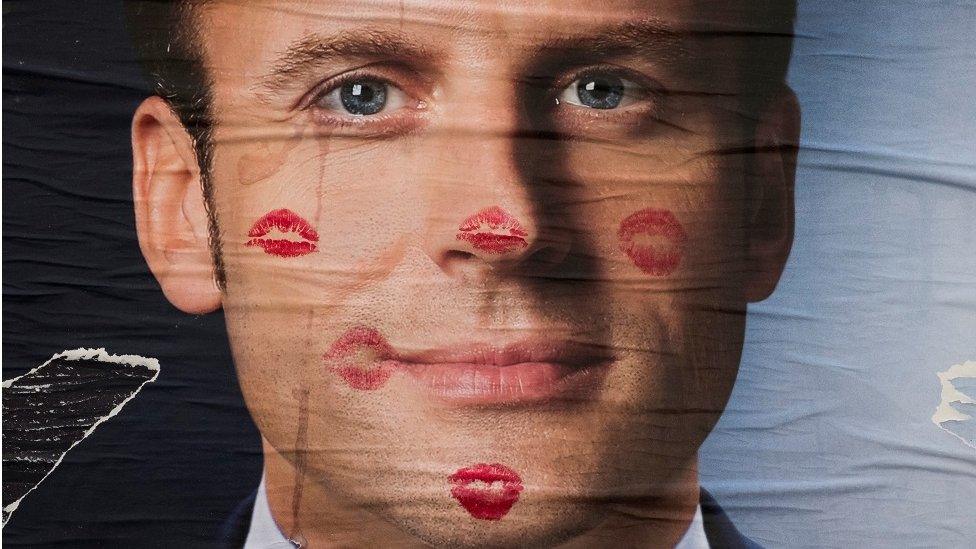

At the party's campaign headquarters on election night, supporters carried blue-coloured roses, Marine Le Pen's favoured symbol.

The heavily defeated candidate even danced, external to I Love Rock and Roll (incidentally demonstrating that whatever presentational skills she possesses do not immediately transfer to the disco floor).

It may have been a strange way for a beaten presidential hopeful to spend the night, but this party has long term plans. Supporters will save their blue roses for 2022.

- Published8 May 2017

- Published7 May 2017

- Published7 May 2017

- Published4 May 2017

- Published7 May 2017

- Published7 May 2017

- Published4 May 2017

- Published3 May 2017