Five reasons why Macron won the French election

- Published

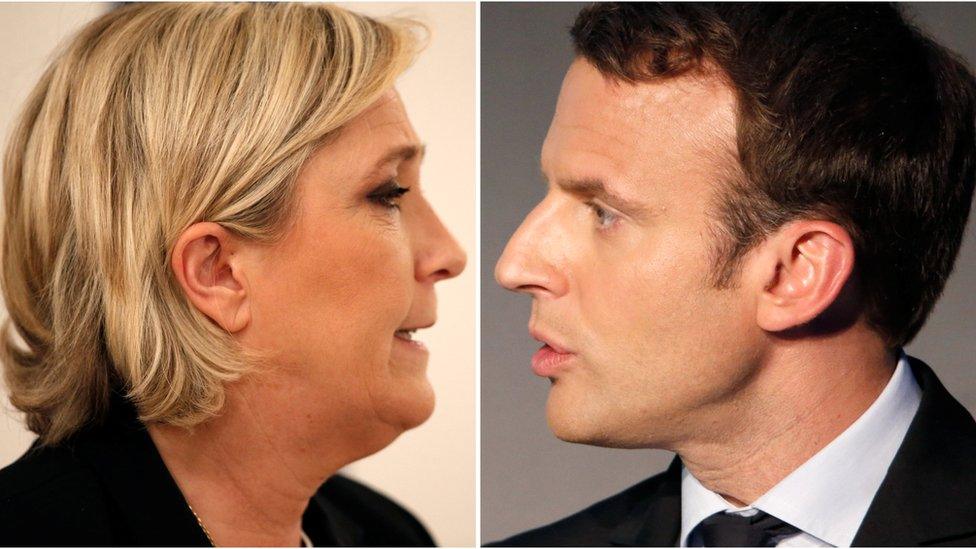

How did a 39-year-old with a new party who has never before been elected win the French presidency?

Emmanuel Macron has triggered a political earthquake in French politics.

A year ago, he was a member of the government of one of the most unpopular French presidents in history.

Now, at 39, he has won France's presidential election, defeating first the mainstream centre left and centre right and now the far right as well.

He got lucky

No doubt about it, Mr Macron was carried to victory in part by the winds of fortune.

A public scandal knocked out the initial frontrunner, centre-right candidate François Fillon; and Socialist candidate Benoît Hamon, already on the left fringe of the party, suffered a very public drubbing as traditional voters looked elsewhere.

A "fake jobs" scandal put paid to the hopes of the early election frontrunner, François Fillon

"He was very lucky, because he was facing a situation that was completely unexpected," says Marc-Olivier Padis, of Paris-based think tank Terra Nova.

He was canny

Luck doesn't tell the whole story.

Mr Macron could have gone for the Socialist ticket, but he realised after years in power and dismal public approval ratings the party's voice would always struggle to be heard.

"He was able to foresee there was an opportunity when nobody could," says Mr Padis.

Instead, he looked at political movements that have sprung up elsewhere in Europe - Podemos in Spain, Italy's Five-Star Movement - and saw that there was no equivalent game-changing political force in France.

In April 2016, he established his "people-powered" En Marche! (On the move) movement and four months later he stood down from President François Hollande's government.

He tried something new in France

Having established En Marche, he took his cue from Barack Obama's grassroots 2008 US election campaign, says Paris-based freelance journalist Emily Schultheis.

His first major undertaking was the Grande Marche (Big March), when he mobilised his growing ranks of energised but inexperienced En Marche activists.

"The campaign used algorithms from a political firm they worked with - who by the way had volunteered for the Obama campaign in 2008 - to identify districts and neighbourhoods that were most representative of France as a whole," Ms Schultheis says.

"They sent out people to knock on 300,000 doors."

The volunteers didn't just hand out flyers - they carried out 25,000 in-depth interviews of about 15 minutes with voters across the country. That information was entered into a large database which helped inform campaign priorities and policies.

"It was a massive focus group for Macron in gauging the temperature of the country but also made sure that people had contact with his movement early on, making sure that volunteers knew how to go door to door. It was a training exercise that really laid the groundwork for what he did this year," Ms Schultheis explains.

And he capitalised on it.

He had a positive message

Mr Macron's political persona appears beset with contradictions.

The "newcomer" who was President Hollande's protege and then economy minister; the ex-investment banker running a grassroots movement; the centrist with a radical programme to slash the public sector.

It was perfect ammunition for run-off rival Marine Le Pen, who said he was the candidate of the elite, not the novice he said he was.

Protester versus pop music - observers said Le Pen rallies couldn't match the positivity on show at Macron gatherings

But he dodged attempts to label him as another François Hollande, creating a profile that resonated among people desperate for something new.

"There is a very prevalent pessimistic mood in France - in a way, too pessimistic - and he comes with a very optimistic, positive message," says Marc-Olivier Padis.

"He's young, full of energy, and he's not explaining what he'll do for France but how people will get opportunities. He's the only one to have this kind of message."

He was up against Marine Le Pen

Up against his more optimistic tone, Marine Le Pen's message came across as negative - anti-immigration, anti-EU, anti-system.

Macron campaign rallies featured brightly lit arenas blaring with pop music, says Emily Schultheis, while Marine Le Pen's mass meetings involved protesters throwing bottles and flares, a heavy police presence, dark audience stands and an "angrier" undercurrent.

Emmanuel Macron's rallies came across as youthful and fresh, while his rival's message appeared more negative

The big TV debate on 3 May was an angry affair, with a string of insults hurled by both sides.

She was a "grand priestess of fear", a snake-oil merchant from the same extremist background as her father. He was a Socialist puppet, a dangerous tool of global finance who would do whatever Germany's Angela Merkel asked.

But many were alarmed by the prospect of a potentially destabilising and divisive far-right presidency and saw him as the last obstacle in her way.

Marine Le Pen may have run a highly effective campaign, but her poll ratings have been on the slide for months. She was ahead in the polls last year, nudging 30%, and yet in just two weeks she has been beaten twice by Emmanuel Macron.

Insults that marked fierce debate

The issues dividing Le Pen and Macron

- Published3 May 2017

- Published24 April 2017

- Published5 May 2017

- Published2 May 2017