Facing jail: Spanish 'stolen baby' who searched for her mother

- Published

Ascension Lopez says she has found documents indicating that her adoption was illegal

"Even if I go to jail, I will remain freer than those who are prisoners of their own lies," says Ascensión López, who faces five months in prison for slandering a nun. "They cannot take away what I know in my mind."

Lopez is too poor to pay €40,000 (£35,000; $46,000) in damages after a court ruled she had wrongly accused the nun of taking her from her biological mother and handing her to ageing adoptive parents in 1962.

If the government does not pardon her, the 55-year-old will be the first person to be jailed over Spain's enormous baby-snatching racket stemming from the Franco era.

Protesters have presented a 30,000-strong petition to Spain's justice ministry calling for her to be let off.

"I have a bone-wasting disease, I have not been able to work for three years and my two children are unemployed and have no contact with their father," a tearful López told the BBC.

Ascension's story

According to López, her adoptive father, a senior figure in Gen Francisco Franco's regime in Almeria whose marriage was barren, bought her for 250,000 pesetas (about €50,000, £44,000 , $57,000 in today's money) via his niece, Dolores Baena, a nun working in a Seville hospital at the time. Her father was 67, and her new mother around 60. Dolores became her cousin.

When she was eight, she came home from school to find local dignitaries in her parents' bedroom. Before her lay her father's body. He had suffered a stroke and died.

"I went to my room to cry, and a member of the family came to see me and asked why I was crying for that man who had nothing to do with me, but had only bought me when I was a new-born."

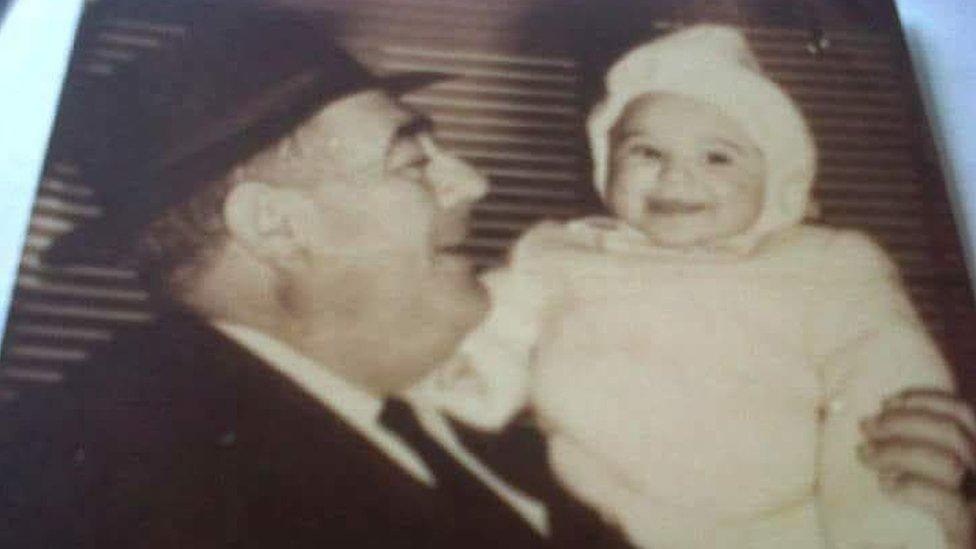

Ascension's adoptive father died when she was eight

Asking for information from her mother and relatives, López began to suspect there was something not quite right about her adoption, long before the issue of babies being stolen from poor or politically suspect parents became a public issue in Spain.

Mystery of Ascensión's three names

For a start, she had different names on the various bits of paperwork that confirmed her identity.

On the first sheet from the Seville hospital nursery where she was kept for a few days, she was called Consuelo.

As a small child, her name was María Dolores - "I was always Loli at home" - but her first identity card named her officially as María Ascensión.

"Whatever happened to my mother, I am very clear that my identity was stolen."

Ascensión López believes she was bought by a senior figure in Gen Francisco Franco's regime

López asked the nun, her cousin, if she could help her trace her background.

"She told me that, try as she might, I would never find my biological parents. When I was 15 she took me to an orphanage in Almeria and showed me all the babies there. 'If we hadn't done what we did for you, you'd have been left alone, like these children with no family'."

Cousins in court

López's investigation has uncovered an adoption sheet signed by Sister Dolores, but the Seville authorities cannot find any document in which her biological mother surrendered her child.

As an activist and president of SOS Stolen Babies Almería, representing other possible victims of the stolen baby scandal that stretches over half a century from the 1930s to the 1990s, López spoke of her case in the media, naming Sister Dolores as the person who "organised" her illegal adoption.

The nun sued her cousin for defamation, winning a 2015 trial. López was ordered to pay a €3,000 fine, plus €40,000 in damages to Sister Dolores and costs.

No documents have been found indicating that Ascensión López was given up by her birth mother

During the trial, Sister Dolores declared: "There was nobody behind the adoption; it was all legal and nobody charged any money."

The judge said Ascensión López had utterly failed to prove that her adoption had been illegally carried out by her cousin and had falsely accused her.

Sister Dolores did not reply to requests by the BBC to comment for this article.

López admits she may have been "careless" in her wording when accusing the nun, but feels let down by the legal system. "I was judged as a daughter, as a mother and as a woman; my whole life was put on trial."

What happened to Spain's stolen babies?

Estimates of the number of cases of stolen babies in Spain range from 30,000 to 300,000.

Manoli Pagador told the BBC in 2011 how her baby son was taken away from her in 1971

Almost all of thousands of cases reported to the courts have led nowhere. But later this year, Eduardo Vela, an 82-year-old Madrid gynaecologist, is due to become the first person to go on trial accused of baby snatching.

López, who cared for her adoptive mother before she died in 1990, says that she too has fallen into bad health and economic ruin. She suffers from a rare bone condition and an inherited blood disorder.

"They have erased my memories. I look at my son and wonder who he looks like. I look at my daughter and wonder if she could have the same disease as me because it's genetically transmitted.

"I just wonder what happened and how did I end up here?"

Timeline of a scandal

2008: Investigating judge Baltasar Garzón writes that 30,000 children were stolen from families considered politically suspect by the Franco regime after the 1936-39 civil war

Thousands of possible victims come forward and new associations are formed demanding justice and help in finding lost relatives in an estimated 200,000 cases

Some 2,000 reported cases of alleged stolen children have been reported but prosecutors have closed all but a handful of investigations

2013: Maria Gomez Valbuena, an 87-year-old nun facing two charges of kidnapping and falsifying documents, dies before going on trial

May 2017: UK MEP Jade Kirton-Darling announces that Spain's Catholic Church and health ministry have promised to open their archives to help those possibly affected by child snatching in the country's hospitals.

- Published18 October 2011