Europe migrant crisis: Italy threatens to close ports as ministers meet

- Published

About 650 migrants were rescued and brought to the Italian port of Catania on Saturday

Germany, France and Italy's interior ministers are to meet for crisis talks as Italy warns the influx of migrants into the country is unsustainable.

Italy has threatened to close its ports and impound rescue ships run by aid agencies carrying people from Libya.

It needs more support as people cross the Mediterranean from Africa in large numbers, the UN's refugee agency said.

More than 500,000 migrants have passed through Italian ports since 2014, and numbers are on the rise again.

Why is Italy under so much pressure?

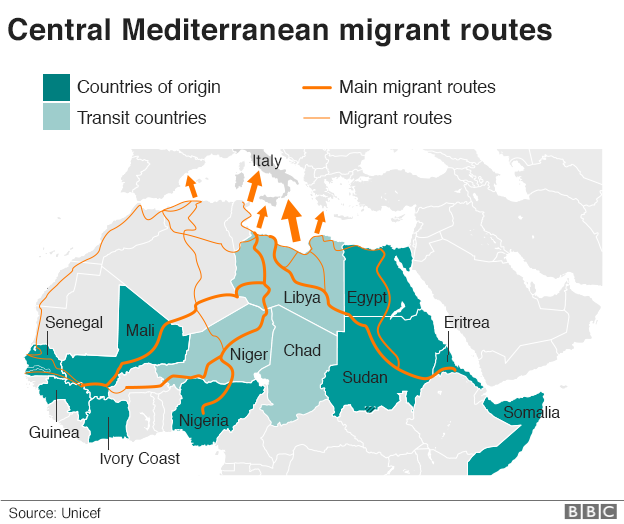

Italy is the main destination for migrants attempting to reach Europe by sea, due to its proximity to Libya.

According to the UN, 83,650 people have reached Italy by sea since the beginning of the year - a 20% increase on the same period in 2016.

Numbers have been rising steeply, with about 12,600 migrants and refugees arriving last weekend alone.

Most migrants make the journey across the Mediterranean in rickety boats, and the UN estimates that 2,030 migrants have died or gone missing since the start of the year.

Libya is a gateway to Europe for migrants from across sub-Saharan Africa as well as the Arabian peninsula, Egypt, Syria and Bangladesh. Many are fleeing war, poverty or persecution.

The UN's refugee agency, the UNHCR, said that among the arrivals in Italy there was an alarmingly high rate of unaccompanied children or victims of sexual or gender-based violence.

Can Rome block rescue ships?

The Italian coastguard takes the lead in co-ordinating rescue operations but many of the vessels run by non-profit groups sail under the flags of other nations, including EU countries like Germany and Malta.

On Wednesday, Italy threatened to stop vessels from other countries from bringing migrants to its ports.

Prime Minister Paolo Gentiloni has accused other European nations of "looking the other way".

Speaking on Sunday, Interior Minister Marco Minniti said: "If the only ports refugees are taken to are Italian, something is not working."

"We are under enormous pressure," he added.

This video from May shows the coastguard rescuing a migrant clinging to a ship's rudder

It is not clear if blocking rescue ships would be legal.

The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea dictates that any ship learning of distress at sea must assist regardless of circumstances, and that the country responsible for operations in that area has primary responsibility for taking them from the ship.

Are other EU countries helping?

Under a solidarity plan agreed in 2015, EU countries were meant to relocate 160,000 asylum seekers between them, to help relieve pressure on Italy and Greece.

The UK and Ireland were exempt from the plan, while Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary voted against accepting mandatory quotas.

So far, only about 20,900 of the 160,000 refugees have been relocated.

The Czech Republic has accepted only 12 of the 2,000 it had been designated, while Hungary and Poland have taken in none.

The EU has begun legal action against the three countries for ignoring "repeated calls" to take their share.

Some EU countries have taken large numbers of migrants separately, including Germany, which had an influx of more than 800,000 migrants in 2015.

Most of them were refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, who arrived in Germany by land via the Balkan migration route.

What do the UN and EU say?

"What is happening in front of our eyes in Italy is an unfolding tragedy," the UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi said.

"This cannot be an Italian problem alone," he added.

On Thursday, the EU's migration commissioner, Dimitris Avramopoulos, promised more financial support for Italy, and urged member states to demonstrate greater solidarity.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published19 April 2017

- Published23 April 2017

- Published29 November 2016