Europe migrants: Tracing perilous Balkan route to Germany

- Published

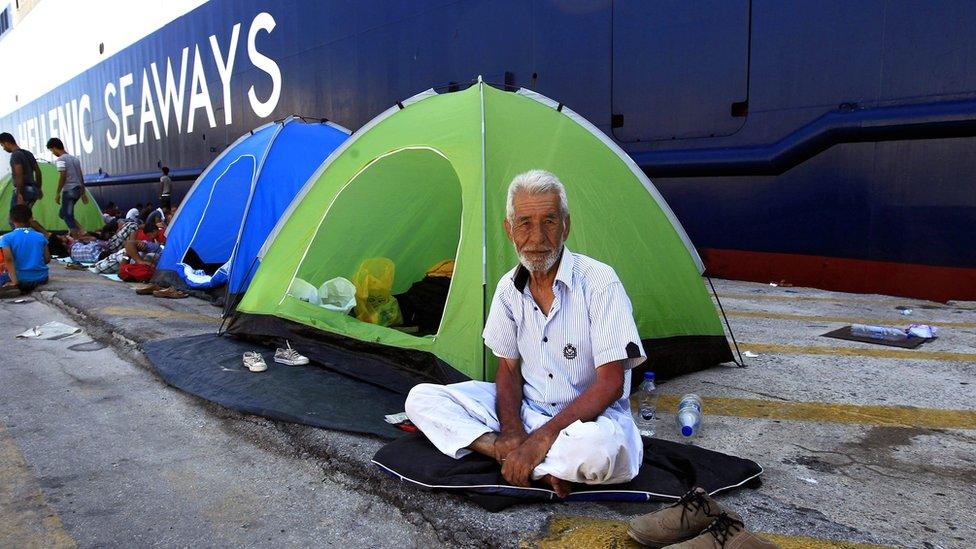

As soon as migrants arrive in Greece, they head for the border with Macedonia

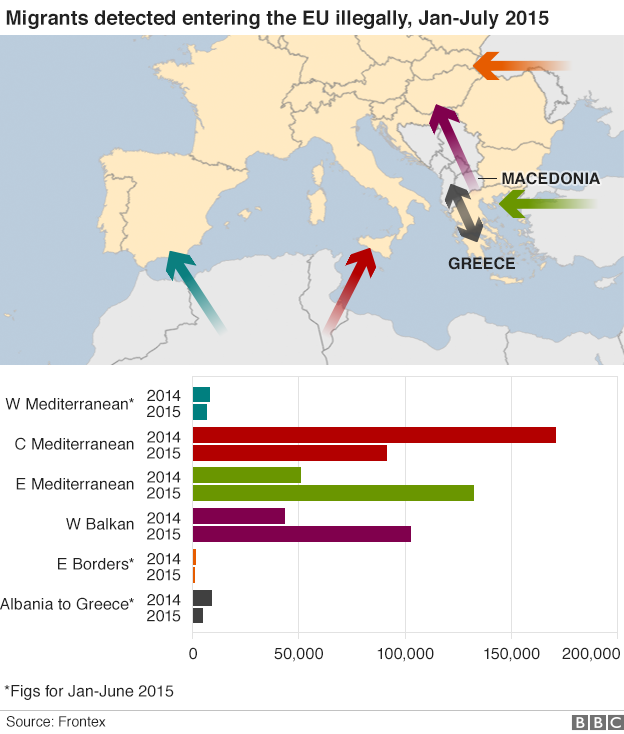

For many thousands of migrants heading to Europe from the Middle East, the long route to a new life now lies through Greece and the Western Balkans with the ultimate destination in Germany and other northern EU countries.

It is a journey fraught with risk, braving the Aegean Sea, Balkan people smugglers and the long path over land through Europe.

BBC correspondents have traced that journey, describing what happens along the route.

Have you made the journey from the Middle East to northern Europe? Let us know about your experiences. Email haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external with your stories.

Dinghy to Greece then fighting for a Macedonia train - by Chris Buckler, Lesbos

Crossing into Europe often means crossing water for the refugees and migrants searching for a new life.

Between Turkey and Greece that can be a short trip, but it is also a dangerous one, particularly for people who have no experience with boats. And many don't.

Before dawn on Turkey's beaches it has become a regular sight to witness people struggling in the darkness with dinghies designed for tourists not travellers.

The migrants use inflatable dinghies to cross from Turkey to the Greek islands in the Aegean

Some are picked up by coastguard ships and there have been others lost to the sea.

The relief is obvious for those who make it to the shores of islands like Kos and Lesbos, but for most that journey is just the beginning.

They then have to register for documents that will allow them to travel on to other parts of Europe and get off the island.

'Hashim' from Syria told the BBC about his journey from Turkey to Serbia, and how he aimed to reach Germany

There are ships to Athens but many families want to go to elsewhere, and that means a long journey north out of the Greek capital, not just through EU countries but also the Balkans.

Macedonia has struggled to cope with the influx of people from Greece, at one stage shutting borders and declaring a state of emergency.

There is now an improvised system for allowing migrants into Macedonia, as the BBC's James Reynolds reports from the Greece-Macedonia border

Macedonia's Gevgelija railway station just across the border has been the most obvious bottleneck.

The migrants need to register at the police station there to get papers, which will allow them 72 hours to cross the country. There have been long queues resulting in further frustrating waits before they get the chance to board a train out of Gevgelija.

Besides, there are regularly too many people for the carriages, leaving the police with the unenviable task of deciding who will be allowed to board and who will have to sleep another night on the platform.

The tracks from here lead towards Macedonia's border with Serbia, another Balkan state on the increasingly well-trodden path through Europe.

Respite in Serbia - by Guy Delauney, Belgrade

The migrants' welcome has been much warmer in Serbia than in Macedonia.

The authorities here have been preparing for an influx for months - and were ready with a temporary reception centre in the border town of Mitrovac as well as a more permanent facility in nearby Presevo.

These were places where people could enjoy food, water and shelter - as well as receive documents granting them leave to stay in the country.

Theoretically, they then have 72 hours to get to one of Serbia's five residential centres for asylum-seekers - but most just use the time to make their way to the border with Hungary, where they hope to cross into the European Union and the borderless Schengen Area.

Western Balkans route

181,500

migrants have arrived in Greece by boat so far in 2015

3,000

expected to enter Macedonia daily

-

90,000 have passed through Serbia since January

-

80,000 asylum applications expected in Austria in 2015

-

800,000 asylum applications expected in Germany in 2015

Many first come to Belgrade, where they change buses, receive cash at money transfer offices or just take a break from a long and often dangerous journey. The square next to the main bus station has been an unofficial refugee centre for months.

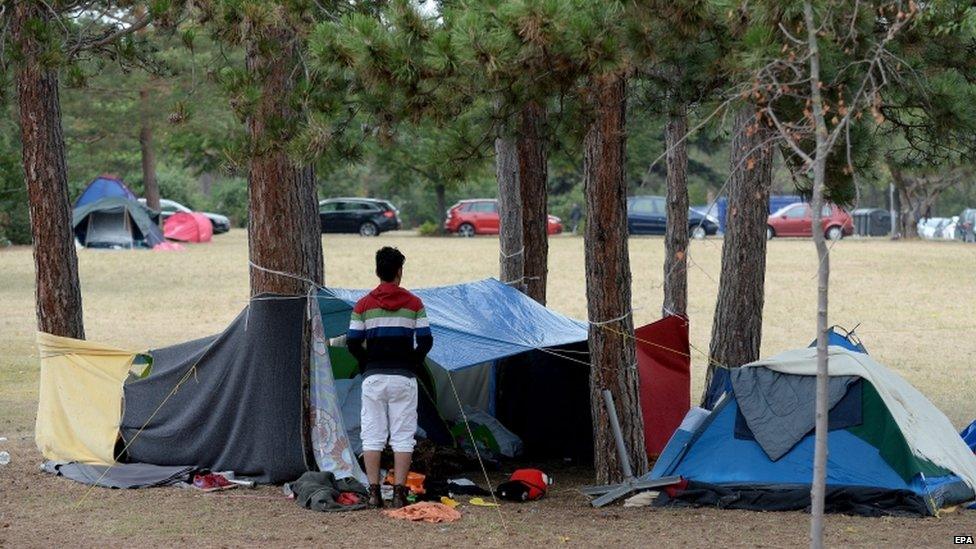

Small groups of well-dressed young men with rucksacks and women with headscarves were also relaxing in the central Tasmajdan park on Monday.

Many are sleeping in a square near Belgrade's bus station

Some were drying out their shoes in the sun, after a soaking on the Greek-Macedonian border.

Serbia's refugee commissariat has registered 90,000 people with temporary "leave to stay" papers so far this year. But only around 500 have entered the country's asylum-seeking process.

For the rest, a new life in such countries as Germany, Sweden or Norway is the dream.

Bypassing Hungary's new border fence - by Nick Thorpe, Roszke

There's a mood of exhausted chaos at the roadside, where more than 100 Afghans, Syrians and Iraqis stretch out on the dry grass.

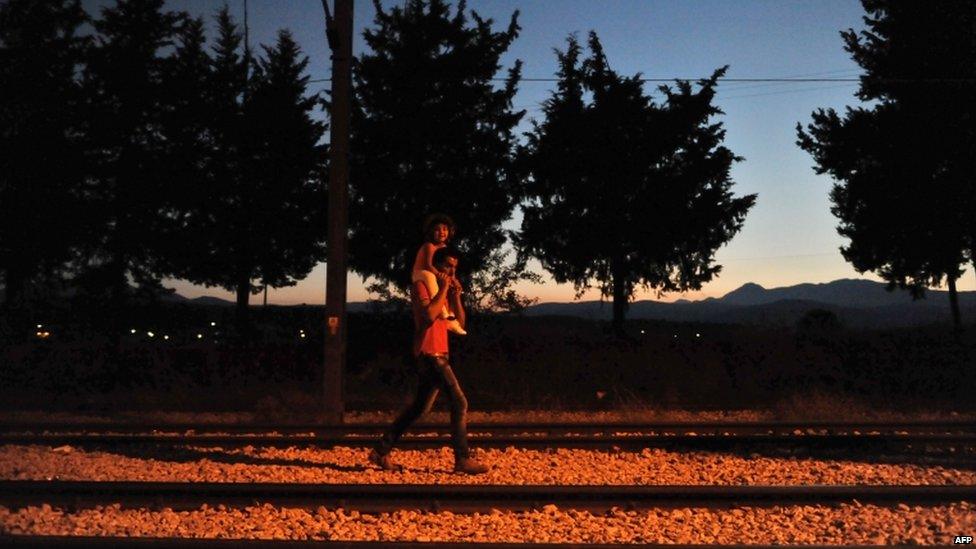

Nick Thorpe reports from a train track used by refugees crossing the Serbia-Hungary border

Hungarian police stand guard, their smart blue uniforms and red caps in sharp contrast with the rags of the refugees.

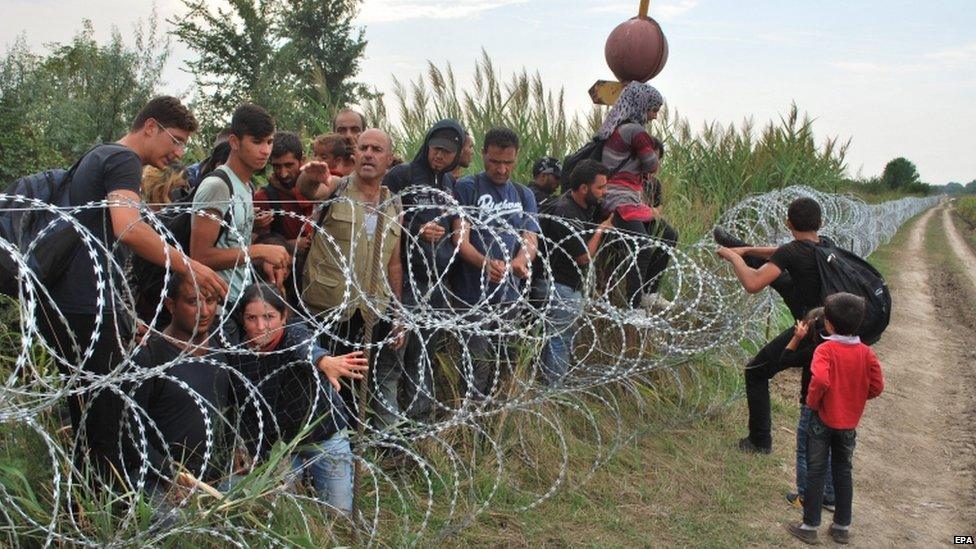

A police bus arrives and people line up to be taken to their first refugee processing centre nearby. Just across an open field, Hungary's new "wire barrier" glistens in the sunlight against the tall stalks of maize.

Hungary's government has so far erected 110 km (68 miles) of the 175 km fence

It consists for now of coils of razor wire - the real fence comes later - and some migrants have just pushed it down or thrown blankets or sleeping bags over it, to lessen the danger of injury.

But at this point on the border, most take the easier option, simply walking down a rarely-used railway line, which cuts a path through the fence. There, more policemen stand to welcome them in English - serious, but not unfriendly: "Carry on down the track - one kilometre."

A bizarre contrast has emerged in Hungary's handling of the refugee crisis. While the government rages against "illegal migrants", police on the border continue to work under procedures in full harmony with their country's obligations under the 1951 UN Refugee Convention.

"Hungary police good. Serbia police good. Turkey and Iran police bad," explains a Syrian man in broken English.

Budapest has three major stations - Keleti, Nyugati and Deli - (East, West and South) are almost overrun with asylum seekers.

Some of the migrants do as they are told, travelling between refugee camps with documents that expire within 48 hours.

But most look for trains, buses, taxis, or car-drivers who will take them to Austria or Germany.

Read more: Hungary's double-sided response to migrant crisis

Austria struggles with new arrivals - by Bethany Bell, Vienna

Many of the migrants arriving in Austria hope to travel on to Germany and elsewhere in northern Europe. Officials in the German state of Bavaria say about 1,400 migrants have crossed the border every day - most of them from Austria.

But, increasingly, people are claiming asylum in Austria - a country of 8.5 million people. Since May, an average of 2,000 people have claimed asylum here every week, according to interior ministry spokesman Karl-Heinz Grundboeck.

In the first six months of this year, more than 28,000 people requested asylum - more than the total for the whole of 2014 - he told the BBC. That number is expected to rise to 80,000 by the end of the year.

Many migrants travel by train through Austria

More than half the migrants come to Austria through neighbouring Hungary and the Balkans, by train, lorry or van.

Groups of migrants, often with children, are becoming a common sight at Austrian railway stations.

Human rights groups have condemned conditions at the Traiskirchen asylum processing camp

In recent days, there has been a spate of accidents in eastern Austria involving vans carrying migrants. Several people have been seriously injured. Some of the drivers were arrested on trafficking charges; others escaped.

Austria's main asylum processing centre at Traiskirchen, south of Vienna, has been overcrowded for weeks.

Hundreds of people, including children, have been forced to sleep outside, as the Austrian federal government and the provinces and municipalities wrangle over where they should be housed.

Amnesty International recently condemned the conditions at Traiskirchen as "shameful", particularly for a rich country like Austria.

Influx threatens to overwhelm German authorities - by Jenny Hill, Berlin

To an onlooker, Germany's system appears dangerously chaotic; when I visited Berlin's reception centre hundreds of refugees stood for hours in intense midsummer heat waiting to be registered.

A volunteer doctor running a makeshift surgery in a nearby tent told me the authorities had been surprised by this sudden influx of people.

Put simply, here's what's supposed to happen to arrivals.

First they register with one of the German states, which provide some money - thought to be around €140 a month (£101;$160) - and temporary accommodation while their asylum applications are processed, That takes, on average, seven months.

If successful, the refugee is then found permanent accommodation by the state.

Jenny Hill visited a reception centre for migrants in Berlin last week

But every state has its own procedures and its own problems. Most are struggling to house the high number of people arriving every day. Refugees are living in tents, converted warehouses, hotels.

I met a Syrian man who pointed to his little girl and told me they had slept on the street for the last few days.

Almost every day the German government reiterates two demands - for other EU member states, the UK included, to take more refugees and for the EU to agree a co-ordinated response to the crisis.

Although attacks on asylum-seeker accommodation are rising, the numbers are relatively low and an extraordinary number of people here are giving up their time or their possessions to help the new arrivals.

Germany's interior minister estimated last week that 800,000 people would seek asylum here this year. He told the BBC he was worried the prevailing attitude of welcome might change. Without the efforts of volunteers, it might struggle to cope.

Have you made the journey to Germany or elsewhere in Europe? Let us know about your experiences. Email haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external with your stories.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also contact us in the following ways:

WhatsApp: +44 7525 900971

Send pictures/video to yourpics@bbc.co.uk, external

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Send an SMS or MMS to 61124 or +44 7624 800 100

- Published3 March 2016

- Published24 August 2015

- Published25 August 2015

- Published18 August 2015