Turkey protesters stage long march against Erdogan

- Published

The marchers wear white T-shirts emblazoned with the Turkish word for justice

At 08:00, the motorway tarmac was radiating heat. There was no shade from the 30C heat, just the exhaust fumes of passing cars.

Not the most pleasant route for a walk. But spirits were high.

"Adalet!" chanted the thousands gathered - "Justice!"

Their white T-shirts emblazoned with the word rapidly became soaked with sweat on day 19 of a 450km (280-mile) march from Ankara to Istanbul.

The movement began when Enis Berberoglu, an opposition MP from the Republican People's Party (CHP), was arrested for allegedly leaking documents purporting to show the Turkish government arming jihadists in Syria, which he denies.

But it has become a wider uprising against what participants see as an erosion of democracy under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Challenging Erdogan's purge

"We are not happy in our country, we don't have any hope," said Leyla, a 70-year-old grandmother, as she joined the march for the first day.

What is wrong with Turkey, I asked?

"Recep Tayyip Erdogan. That's all."

The protesters intend to reach their destination of Istanbul on Sunday

The marchers are fighting Turkey's erosion of democracy, though it is the nationwide purge of the past year that has united them.

The failed coup last July saw rogue soldiers bombing government buildings and driving tanks into civilians, killing more than 260.

Since then, over 50,000 people have been arrested and 140,000 dismissed or suspended.

Opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu began the march on 15 June and his stance has galvanised supporters

There is a widespread feeling that the government has seized the chance to crush all opponents, not just alleged coup supporters.

Among the marchers was Ulas Bayraktar, a former political science professor at Mersin University in southern Turkey. In April, he was fired by a government decree.

He was one of 1,100 academics who had signed a petition calling on the government to cease armed conflict in Kurdish-dominated areas - and paid the price for dissent.

Fired academic Ulas Bayraktar says he has nothing more to lose by marching against President Erdogan

"I see this as a call for justice but also for democracy, for peace," he said. "I lost my job for this demand so it's normal that I'm here. I want to be hopeful because we are approaching the bottom of the sea. And if your feet touch the bottom, you can rise up very quickly."

The march was launched by the CHP leader, Kemal Kilicdaroglu.

Long criticised as weak, the sprightly 68-year-old has suddenly hit his stride, even being compared to Gandhi for the Salt March against British colonial rule in the 1930s. Doctors check him after each day of walking and he alternates pairs of trainers to ease the pain.

"We want to make Turkey civilised," he told the BBC during a midday break from the sun.

"We need justice, not MPs, journalists and academics in prison. There's no independent judiciary. We'll continue our fight until we get democracy and the authoritarian regime collapses."

Marchers are sustained by watermelon and meatballs at the end of the day

President Erdogan has lambasted the march for "supporting terrorist groups", with Mr Kilicdaroglu hitting back that it shows "the mindset of a dictator".

But, mindful that intervening could provoke a backlash, the government has allowed it to go ahead and police and soldiers provide protection.

The march is due to culminate on Sunday near the prison in Istanbul where the MP, Enis Berberoglu, is being detained, but organisers say they want to build on it in the months ahead.

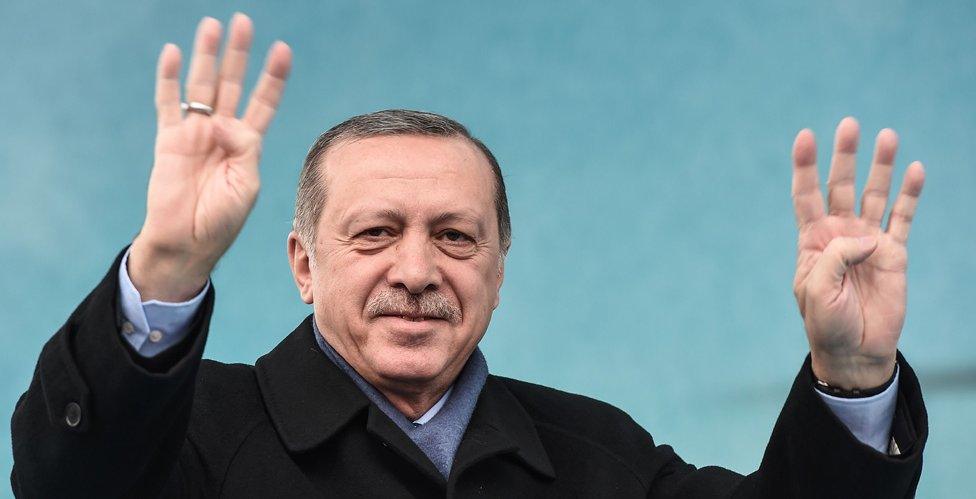

Four-fingered salutes and blisters

Along the way, most passing vehicles hooted their support. But other drivers chanted the Erdogan campaign song.

President Erdogan gives the four-finger Islamist salute - the "rabaa" - which came from Muslim Brotherhood protests in Egypt in 2013

As we neared the town of Izmit, 100km from Istanbul, garage workers gathered to make a four-finger Islamist gesture promoted by the president.

"This is not a way to seek justice," said one, Hakan Murat. "It can be found in courts, not by inciting people on the streets. The CHP is sheltering terrorists, while we're dying for our nation. It makes us angry."

As the daytime heat subsided, the crowd prepared to walk again, treating blisters and rejuvenated by watermelon and meatballs.

Opposition's glimmer of optimism

A kilometre-long Turkish flag was unfurled along the motorway, held aloft by participants for the final stretch of the day.

Protests here have come and gone over the years and the opposition is notoriously fractured. But this simple movement has gained momentum, with a feeling that the marchers have finally found a positive and peaceful way to challenge an increasingly authoritarian government.

Along the motorways and hills of the route between Ankara and Istanbul, a glimmer of optimism has been kindled.

For the organisers and the marchers, the task now is to build on it if they are to pave an alternative road ahead for Turkey.