Barcelona attacks: What could they mean for Catalan independence?

- Published

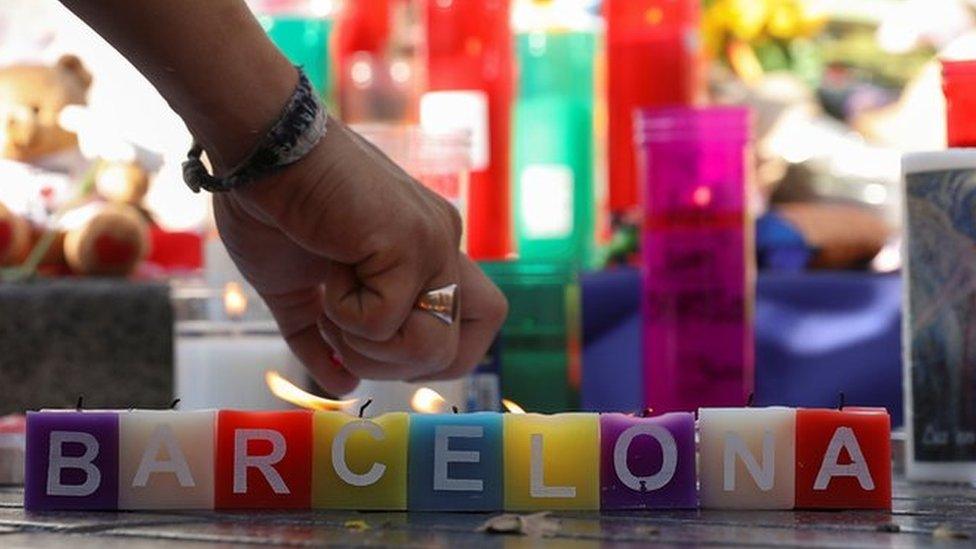

King Felipe VI joined a minute's silence in Plaça de Catalunya

Ten years ago this month, a foreign news event occurred that ultimately had a major impact on relations between Catalonia and the rest of Spain.

The credit crunch, which began when French bank BNP Paribas froze funds over US subprime mortgage sector fears, eventually plunged Spain into recession.

Old grievances among Catalans were revived, as secessionists argued that their wealthy region was being milked by incompetent governments in Madrid.

Now a very different kind of outside factor, jihadist violence, has returned to Spain, which last saw such carnage in the Madrid train bombings of 2004.

This time Catalonia was attacked, less than two months before its unrecognised referendum on independence.

While there is no suggestion Barcelona was targeted for any reason other than being Barcelona, could the attack become the wild card that gives the sovereignty game back to Madrid?

Because they clapped the king of Spain on Plaça de Catalunya?

Probably not.

When King Felipe and Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy joined Catalan President Carles Puigdemont and Barcelona Mayor Ada Colau at a rally on the city's central square, they were simply there to mourn.

"How could the king and the prime minister not travel to Barcelona?" says Manuel Arias-Maldonado, political science professor at Málaga University. "They had to go."

Signs reading "Long live Spain" and "Long live Barcelona" on the Ramblas

For Adrià Alsina Leal, professor of journalism and communications at the Central University of Catalonia and a Catalan independence activist, "solidarity is welcome from wherever it comes".

"It's only normal that they came," he says, noting the sense of "correctness and politeness" at the event. "I wouldn't attach any other significance to that."

"It could even be argued that circumstances have forced Puigdemont and Rajoy to show, albeit reluctantly, some unity of purpose," Prof Arias-Maldonado suggests.

"There are, of course, minor details: Puigdemont's references to the 'Catalan character' in his speech, Rajoy's call to co-operate and leave behind what separates in the face of greater challenges."

How long will the correctness last?

The tacit truce between Madrid and the secessionists may rapidly unravel after Sunday, when Catalonia's three days of official mourning end.

Activists have suspended campaigning for that period, and I saw no sign of campaigning along Las Ramblas, beyond the occasional estelada (the unofficial lone-star flag of independence) in some of the shops.

But secessionists are indignant at how some of Spain's biggest newspapers have used the attack against their cause.

For instance, an editorial in El País, external essentially argued that an attack of this magnitude should act as a reality check for Catalans and persuade them to set aside thoughts of independence.

"Using an editorial to sort of shame Catalan independence supporters like that was probably a bit over the top," says Prof Leal.

However, the real battle for hearts and minds may be fought on social media.

Some secessionists, Prof Arias-Maldonado points out, are already praising the response of Catalan "state-like structures" as confirmation that Catalonia is ready for independence.

"Some are even advancing the idea that these things would not happen in a free Catalonia," he says.

Adrià Alsina Leal is a long-time independence campaigner

Prof Leal insists that he and fellow members of the Catalan National Assembly (ANC), a non-party grassroots movement advocating the referendum and a Yes vote, are showing dignified restraint during the period of mourning.

However, when the campaign restarts, it will be visibly in tune with its democratic values.

On the other hand, he says: "We definitely need to go in a very micro-targeted way to all those people who might still be wondering whether to vote Yes or No or whether to vote at all."

Why is everyone talking about the Catalan police?

Among the most extraordinary sights of the past few days was the outpouring of real love for Catalonia's police. People applauded the Mossos in the street for their work in securing the region and tracking down the jihadists.

In a blistering polemic entitled Seven Hours Of Independence, external, Catalan writer Bernat Dedéu argues that the first response of Catalonia's police and emergency services proved the region had "acted as an authentic power".

Armed police are a familiar sight in Barcelona now

He also makes the point that Spain has denied Catalan police direct access to European police databases, while granting it to police in the Basque region (however, change was already on the cards last month).

Nonetheless, the Catalan authorities' handling of security before the attack is not above criticism.

Barcelona's town hall rejected installing vehicle barriers at Las Ramblas, despite a recommendation from the Spanish interior ministry after the Berlin Christmas market attack, Prof Arias-Maldonado points out.

He also notes that the explosion at a house in Alcanar just before the attack was "misinterpreted as a drug-dealing event".

"It is unclear why this happened and why this event was not followed by a tightening of the security," he says.

"Still, perception is king and if public perception says that the Catalan police handled it well, it might help the secessionist case."

How strong is the appetite for secession?

"It is hard to say," says the political scientist from Málaga University.

"According to polls, secessionists are now around 41% of Catalans - numbers have been going down for some time. Around 49% are against it.

"These data come from the Catalan public polling body, external. How will the terrorist attack affect this situation? Who knows? But my bet is - not very much and if it does, it will reinforce the unionist side.

"Ultimately I don't think the essence of the independence debate is going to change, because the underlying situation has not changed," says Prof Leal.

A pro-independence campaign meeting in Barcelona, September 2015

When I put it to him that support for the cause of independence appears to be ebbing, he is sceptical about the polls and argues that the base is still strong.

"I don't know anybody who was a supporter of independence who has stopped being a supporter of independence," he says.

He speaks with the same passion I remember in November 2014, when we met during the heady week of Catalonia's referendum dry run.

Nearly two million people voted, defying Madrid's attempts to ban it, and 80% chose independence (according to Catalan figures).

But one thing has definitely changed since then: Spain's economy is recovering.

That, for Prime Minister Rajoy, master of the long game, may yet be his best card.

For more on Barcelona after the attack, follow Patrick at @patrickgjackson, external

- Published21 August 2023

- Published9 November 2014

- Published20 August 2017

- Published18 August 2017

- Published27 August 2017

- Published27 August 2017

- Published18 August 2017

- Published18 August 2017

- Published18 August 2017

- Published18 August 2017