German election: Why this is a turning point

- Published

Angela Merkel may have won but her position at the head of the CDU is weakened

Angela Merkel has won four more years as chancellor and will continue to command the stage in Germany. But this is her party's worst performance with her as leader and overnight Germany's political scene has changed.

The third biggest force in Germany is the nationalist and populist right of Alternative for Germany, or AfD.

So what does this shake-up mean for Germany?

What has changed?

On the surface, very little. But in reality everything has. Germany is at a turning point.

Angela Merkel has secured a fourth term, but she knows she has presided over the CDU's worst electoral performance since 1949.

For the first time since the 1950s, Germany will have six parties in the Bundestag, and the two giants of the political centre are at their lowest ebb.

Election marks shift in German politics

Mrs Merkel's main challenger, Martin Schulz, dubbed her "the biggest loser", even though it was his centre-left SPD that registered its worst ever showing and, barring a dramatic change of mind, will form the opposition.

Nationalists take national stage

The real winners of this election are the nationalist, right-wing AfD and the pro-business FDP, who have returned to parliament after four years in the wilderness and are likely to return to government.

Within an hour of AfD's success becoming clear, joint leader Alexander Gauland promised to "hunt down the government, Mrs Merkel, and get our country and people back". They will be a loud, confident opposition party with the chancellor in their sights.

Alice Weidel of AfD promised party supporters to push for a committee to investigate Mrs Merkel's decision to allow migrants into Germany

With more than 90 seats in the Bundestag and 13% of the popular vote they will make life very uncomfortable for her government. They argue the chancellor has broken a number of laws with her refugee policy and say a committee should investigate her.

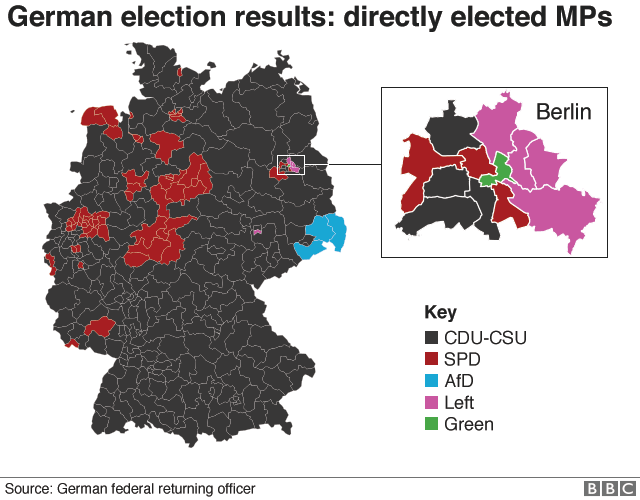

Take apart the right-wing party's results and you will see a big east-west split. AfD are the second biggest party in the east of the country with over 20% of the vote. In the eastern state of Saxony they were even neck and neck with the CDU on just under 30%.

Amongst men in the east they were the most popular party, three points ahead of the CDU.

Their showing in the west was around 11%.

AfD attracted a million voters from the CDU and 470,000 from the SPD, as well as over a million new voters.

So why did people vote AfD?

They simply addressed the concerns of voters worried about the influx of migrants and refugees. A fascinating survey of AfD voters, external on Sunday showed:

99% felt the party had a better understanding that people did not feel safe any more

99% agreed with AfD's policy to reduce the influx of Islam in Germany

96% backed their plan to restrict severely the arrival of migrants and refugees

85% felt they were the only party they could register their protest with

The AfD's campaign featured a poster saying "Burkas? We like bikinis"

If this election was just about the economy, the two parties that have steered Germany through the past four years would have sailed through.

Germany's economy is doing very nicely, thank you. GDP is growing, unemployment is low and the government receives more in tax than it spends.

But this was the first federal vote since the Merkel government opened Germany's doors to an influx of migrants and refugees in 2015, letting in over around 1.3 million people.

The conservative chancellor promised Germans they would manage, and they did. Asylum applications have fallen dramatically in the past year and Mrs Merkel has taken a tougher line on deportations.

But the issues of asylum, integration and deportation of failed asylum seekers hovered over the entire campaign to such an extent that immigration monopolised the only TV debate between the two challengers for chancellor, Mrs Merkel and Martin Schulz.

And AfD were the party that benefited most, even though they were not in the studio. Their poll numbers went up as the campaign progressed.

Rarely has the general atmosphere in the country been so toxic and confrontational during an election campaign, Focus magazine observed.

How right-wing are AfD?

One very revealing number from the survey of AfD voters was that 55% believed the party did not distance itself sufficiently from far-right positions. In other words, more than half the party's voters felt they were too extreme but voted for them anyway.

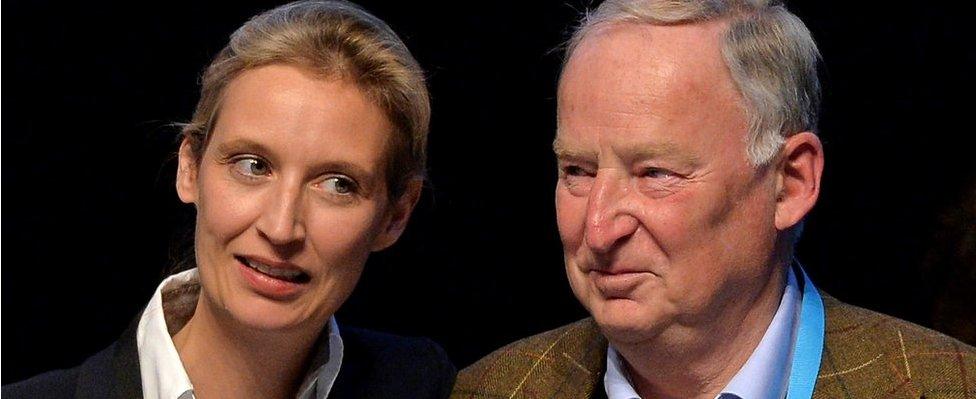

Alice Weidel (L) and Alexander Gauland (R) have both been caught up in remarks condemned as far-right

They espouse anti-immigrant and anti-Islam policies and several of their leading figures have made remarks widely condemned as extremist. Their programme calls for a ban on minarets and considers Islam incompatible with German culture. "Islam does not belong to Germany," the party believes.

Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel warned voters ahead of the poll against having "real Nazis in the German Reichstag for the first time since the end of World War Two". Germany's Central Council of Jews said its worst fears had come true.

What they have said:

Joint leader Alexander Gauland has called for Germans to reclaim their history: "We have the right to be proud of the achievements of the German soldiers in two world wars." He has also said integration commissioner Aydan Özoguz should be "dumped" back to her parents' country of origin, Turkey. Last year he said he would not want a black German footballer as a neighbour

A 2013 email from lead candidate Alice Weidel was unearthed during the campaign in which she made derogatory remarks about Arabs as well as Roma and Sinti (Gypsies). Ms Weidel rejected the report as "fake news"

Another candidate, Frauke Petry, suggested in 2016 that migrants should be shot at "if necessary", to stop them entering Germany illegally

More on AfD:

Will 'Jamaica' run Germany now?

A so-called Jamaica coalition may be the only option open to Angela Merkel, now that Martin Schulz has ruled out a "grand coalition" of the two old giants. She wants to talk to the SPD, but he wants to lead the opposition and not leave the job to AfD.

Jamaica appears to be the answer for Angela Merkel's coalition negotiations

So that leaves Jamaica, named after the colours of the parties involved: the black of the CDU, the yellow of the liberal FDP, and the Greens.

It is an unlikely pairing and there is little precedent for it. A prototype has just begun work in the northern state of Schleswig-Holstein, but there are genuine differences between the liberals and Greens.

The Greens want to phase out 20 coal-fired power plants and the FDP disagree. But Mr Schulz thinks it could work: "I think this might be what the country needs," he said late on Sunday. "The parties on the right and left as part of this opposition - this will lead to the debates we need to be having."

And what if the Jamaica talks fall flat? Germany could be staring at early elections because the idea of a minority government has never existed on a federal level and Angela Merkel has appeared to rule it out.

Faces to watch

Christian Lindner's FDP hopes to return to government, despite four years spent outside the Bundestag

If the FDP returns to power, watch out for its leader, Christian Lindner, a charismatic 38-year-old who has tried to focus on education and a "digital first" campaign. Party colleague Alexander Graf Lambsdorff will also be eyeing a top job.

Katrin Göring-Eckardt of the Greens will be focusing on climate change in coalition talks

The left-leaning Green Party is led by centrists Katrin Göring-Eckardt and Cem Özdemir. He has called for Angela Merkel to be much tougher with Turkey, while she has held positions in the Protestant Church.

The Greens will be looking for guarantees from the chancellor on environmental protection and the Paris climate change pact. "The social question is going to be at the heart of these debates about the future, and if the SPD is not interested in governing, we will be the party to carry this debate, especially in coalition talks," says Ms Göring-Eckardt.

- Published12 September 2017

- Published22 September 2017