German election marks unprecedented political shift

- Published

Merkel looks set to win a fourth term as Chancellor - but in a wholly different German political landscape

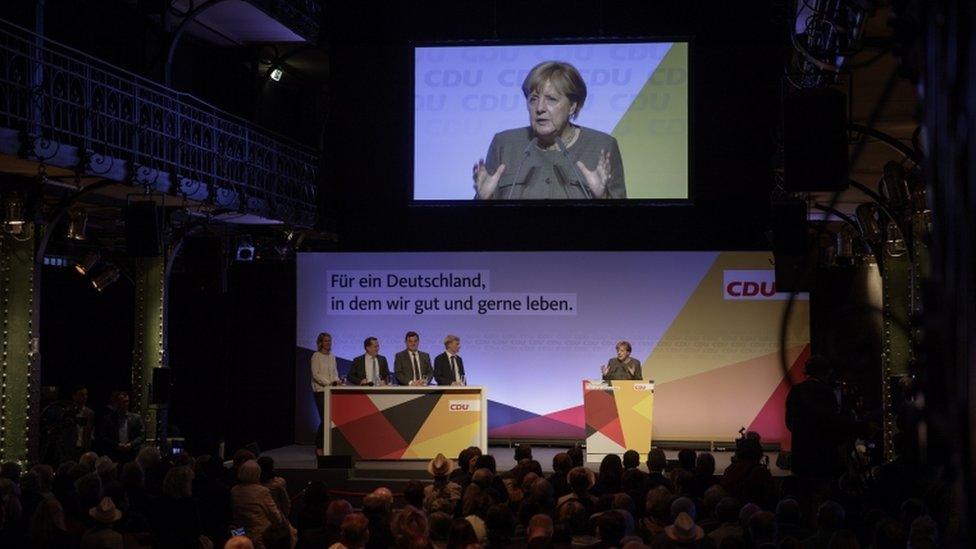

Rock music blaring, supporters cheering, Angela Merkel sweeps on to the makeshift stage. Under spotlights hastily rigged above what's usually an indoor tennis complex, the chancellor is relaxed and smiling as she acknowledges the applause of her loyal fans.

A few exuberant refugees - carefully chosen and given front row seats - wave a huge banner. Almost unnoticed, security staff quietly hustle a couple of scruffily dressed men out of the hall. Mrs Merkel has been heckled several times on the campaign trail by supporters of the right-wing party Alternative fuer Deutschland (AfD). No one here is taking any chances. In fact her rallies have been moved to indoor venues during the last week of campaigning.

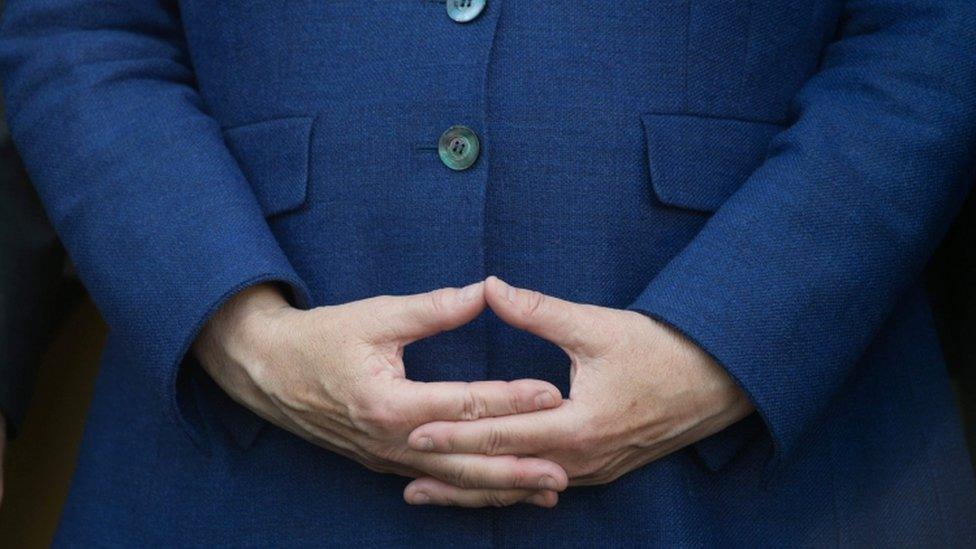

As she launches into a well-rehearsed speech without notes, Angela Merkel knows she will - most likely - win this election. To many Germans she represents strength and stability in the shifting world of global politics. Her carefully stage-managed campaign is designed to reflect her experience; 12 years in the job. Even Mrs Merkel's trademark hand gesture - fingers held together to form a diamond shape while she speaks - has been replicated on the banners held up by the cheering audience.

Angela Merkel has already spent 12 years in the role

If the polls are right, a clear majority of German voters will choose Angela Merkel as their leader for the next four years. But then German voters don't have much choice. In the centrist politics of Germany today, commentators note that it can be hard to distinguish the mainstream parties from one another. And Mrs Merkel hasn't had to work particularly hard to see off the diminishing challenge of social democrat Martin Schulz.

Traditional values

In the old marketplace of Schwerin, shoppers have mixed views. One woman tells me that "Mrs Merkel is a bit too soft. She seems easily influenced. I can't decide who to vote for".

Both Mrs Merkel and the AfD divide opinion on issues such as immigration

The man selling honey at a nearby stall says: "I like her a lot. She has very good policies and I particularly like her refugee policy."

But a young woman adds: "The big parties are already in power and they didn't do that much good. I don't want to support them with my vote."

Around the corner the smashed windows of a shop front tell the real story of this election. The local AfD headquarters has been repeatedly vandalised. Someone has scrawled "hate Nazis" on the building. AfD's anti-Islam, anti-immigrant rhetoric may horrify many Germans but in this region, in Germany's old east, one in five voters are expected to support the party.

As we walk along the lakeside here, among gulls and swans, Rolf Kronhagel explains why he shifted his allegiance to AfD. He's a teacher who turned his back on the social democrats.

It was AfD's opposition to gay marriage that first won him over, he says. He likes their focus on traditional family politics. He also likes their stance on migrants. Mr Kronhagel teaches new arrivals the German language and explains that, in his experience, whilst many want to work and integrate, too many refuse to assimilate into German culture and society.

The AfD has seen a resurgence in the German polls

"In a way," he says, "AfD is already sitting at the table of government. It's the most influential party in Germany because it breathes down the neck of the mainstream parties.

"You can see the concrete results of that in Germany's new asylum laws. People are tired of hearing the same old things."

Becoming mainstream

Nationally, support for AfD surged during the refugee crisis but diminished as migrant numbers fell. But it's climbed back up in the polls, largely thanks to a campaign which focuses on immigration. One shows a pregnant white woman with the slogan "New Germans? We make them ourselves". Another shows two bikini clad white women along with the catchphrase "Burkas? We like bikinis".

The AfD campaign and emphasis on anti-immigration rhetoric has divided Germans

AfD is on course to comfortably win seats in parliament. It would be the first time since WW2 that a far-right party is represented in the Bundestag. It Is estimated that around one in 10 Germans support the party. What began life on the political fringe is fast becoming mainstream.

The established parties here say they won't do business with AfD but it may yet emerge as the third largest group in the next Bundestag. Polls suggest there may be six parties altogether in the next parliament (there are currently four). A place which prides itself now on compromise and consensus is likely to be a rowdier, more fractious place.

Those who describe this election as dull, this campaign as lacklustre, miss the fact that something really significant is happening here. The 2017 election marks an unprecedented shift in both the tone and substance of post-war German politics. What is the political norm in many other European countries was unthinkable here. Not any more.

- Published25 September 2017