Europe migrant crisis: EU court rejects quota challenge

- Published

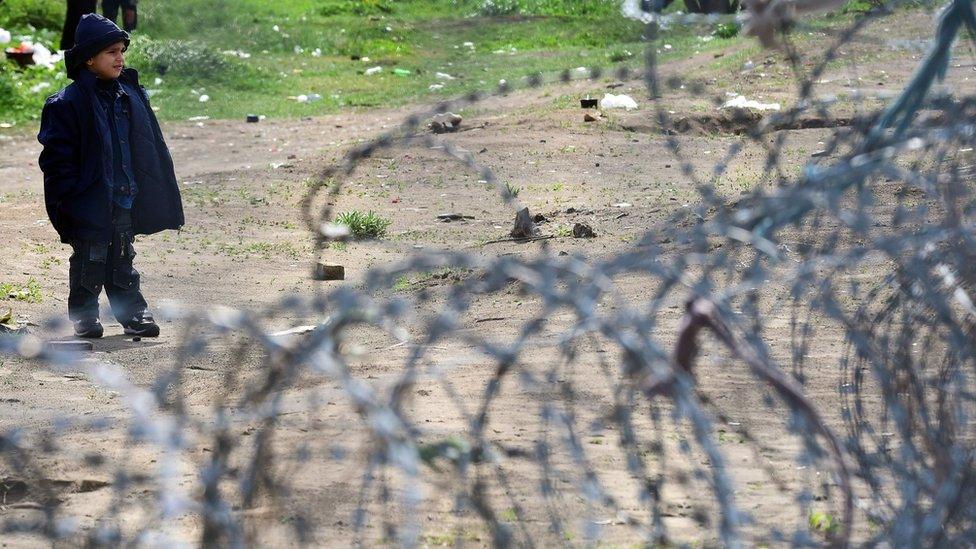

Hungary has built a controversial anti-migrant fence on its southern border with Serbia

The EU's top court has rejected a challenge by Hungary and Slovakia to a migrant relocation deal drawn up at the height of the crisis in 2015.

The European Court of Justice overruled their objections to the compulsory fixed-quota scheme.

Hungary has not accepted a single asylum seeker under the scheme since it was introduced two years ago.

It was an attempt to ease the pressure on frontline countries such as Greece and Italy.

But the ruling has sparked fury, with Hungary's foreign minister vowing: "The real fight starts now."

Why was this scheme introduced?

Since 2014, about 1.7 million migrants have tried to make new homes in the EU in the worst migrant crisis since World War Two.

Those fleeing war and persecution, many from the Middle East, are entitled to asylum under European and international law.

The numbers peaked in 2015, and in September that year, European leaders agreed to spread a total of 160,000 migrants "in clear need of international protection" among member states over two years.

To date, only 28,000 people have actually been relocated.

Why did it cause a row?

The issue was decided by a majority vote - a system only usually used on issues that do not affect national sovereignty.

Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Romania voted against.

Hungary was asked to take 1,294 asylum seekers, Slovakia 802.

Slovakia has taken only about a dozen, while the Czech Republic has refused to take any for the past year.

To date, Poland and Hungary have refused to take a single asylum seeker under the scheme. That's not to say they have refused all asylum applications - Hungary accepted 444 from January to July this year. But it will not co-operate with this "solidarity" scheme.

Why didn't Hungary and Slovakia want to take in the asylum seekers?

In asking the court to annul the deal, Hungary and Slovakia argued at the Court of Justice that there were procedural mistakes, and that quotas were not a suitable response to the crisis.

Officials say the problem is not of their making, that the policy exposes them to a risk of Islamist terrorism and that it represents a threat to their homogenous societies.

Their case was supported by Poland, where a right-wing government has come to power since the 2015 deal.

But it was rejected by the ECJ which argued that the agreement "actually contributes to enabling Greece and Italy to deal with the impact of the 2015 migration crisis and is proportionate".

As efforts to relocate asylum seekers around the continent stall, many remain in limbo in camps here in Greece, and in Italy

It rejected the complainants' argument that the scheme should have been adopted unanimously.

What's been the reaction to the ruling?

Hungary's Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto was furious, calling it "appalling and irresponsible". He vowed to use all legal means against the judgement, which he said was "the result of a political decision not the result of a legal or expert decision".

"Politics has raped European law and European values. This decision practically and openly legitimates the power of the EU above the member states," he said.

"The real fight starts now."

In a milder statement, Slovakian Prime Minister Robert Fico said his country's position on quotas also "does not change".

EU Migration Commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos tweeted, external: "Time to work in unity and implement solidarity in full."

In other comments, he lamented that some member states "continue to show no solidarity".

German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel urged "all European partners to... implement the agreements without delay."

What happens now?

The court's decision is final and cannot be appealed.

Mr Avramopoulos warned after the meeting that if those nations resisting the scheme did not change their ways, "we should consider to take the last step in the infringement procedure, taking Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic to the European Court of Justice".

Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic are already facing legal action by the EU executive, the European Commission, for their inaction over the relocation of asylum seekers.

The three states could be referred to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and eventually face heavy fines.

On the other hand, initiatives such as the EU-Turkey deal and EU measures to curb migration from Libya have led to a significant drop in irregular migration - giving officials a little more breathing space to find a compromise, say correspondents.

However, many thousands of migrants still remain stuck in camps in Italy and Greece - desperate for a permanent new home.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published13 June 2017

- Published6 July 2017