Europe migrant crisis: EU blamed for 'soaring' death toll

- Published

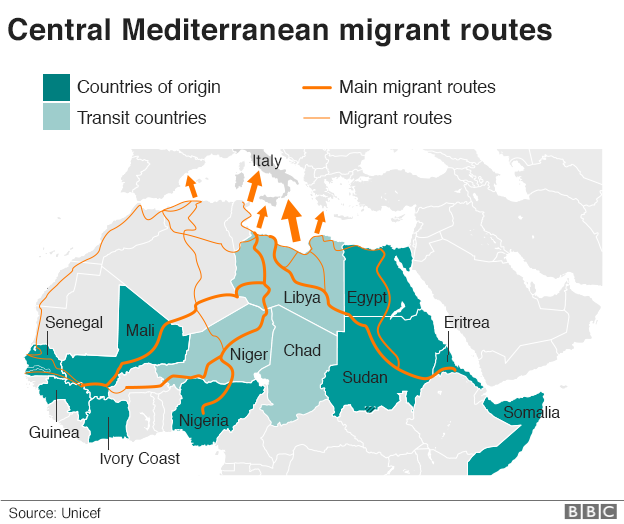

Italy - due to its proximity to Libya - is the main destination for migrants attempting to reach Europe by sea

Amnesty International has blamed "failing EU policies" for the soaring death toll among refugees and migrants in the central Mediterranean.

In a report, it said "cynical deals" with Libya consigned thousands to the risk of drowning, rape and torture.

It said the EU was turning a blind eye to abuses in Libyan detention centres, and was mostly leaving it up to sea rescue charities to save migrants.

More than 2,000 people have died in 2017 trying to get to Europe, it said.

The EU has so far made no public comments on Amnesty's report.

It comes as interior ministers from the 28-member bloc are meeting in Tallinn, Estonia, to discuss the migrant crisis.

They will review a $92m (£71m) action plan unveiled by the European Commission to deal with the issue.

The commission proposes to use more than 50% of the funds to boost the Libyan coastguard's capacity to stop traffickers launching boatloads of migrants out to sea to be rescued.

The rest is to help Italy feed, house and process the migrants who get there.

Italian ports have continued to see a large number of migrants arrive in the past year, putting stress on the country's asylum system. Earlier this month, officials suggested closing Italy's ports to foreign rescue ships - something which is legally difficult, but indicative of the strain the country is under.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees added his voice to calls for more assistance for the Mediterranean nation from the international community.

"What is happening in front of our eyes in Italy is an unfolding tragedy," Filippo Grandi said at the time. "This cannot be an Italian problem alone."

This video from May shows the coastguard rescuing a migrant clinging to a ship's rudder

Italy's problem is partly attributed to the instability in nearby Libya, which is largely controlled by a multitude of armed militias, loyal to rival government factions. The country has been embroiled in widespread conflict since the downfall of Col Muammar Gaddafi in 2011.

In the power vacuum, people smugglers operating from the country's north coast are putting African refugees to sea in the hope of reaching Italy, often on flimsy rafts which cannot make the entire journey. Instead, humanitarian vessels rescue them from the water and deliver the migrants to the nearest port - an Italian one.

"Rather than acting to save lives and offer protection, European ministers... are shamelessly prioritising reckless deals with Libya in a desperate bid to prevent refugees and migrants from reaching Italy," said John Dalhuisen, Amnesty's Europe director.

"European states have progressively turned their backs on a search and rescue strategy that was reducing mortality at sea in favour of one that has seen thousands drown and left desperate men, women and children trapped in Libya, exposed to horrific abuses," he said.

Amnesty's report said measures implemented by the EU to strengthen search and rescue in the central Mediterranean in 2015 had dramatically decreased deaths at sea.

But this priority was short-lived, the document said, adding that the EU later shifted its focus to disrupting smugglers and preventing departures from Libya.

Such practices and an increasing use of unseaworthy boats had made the sea even more unsafe, Amnesty said.

Interceptions by the Libyan coastguard often put refugees and migrants at risk, the rights group warned.

It said that there were serious allegations that coastguard members were colluding with smugglers and abusing migrants.

"If the second half of this year continues as the first and urgent action is not taken, 2017 looks set to become the deadliest year for the deadliest migration route in the world," Mr Dalhuisen said.

"The EU must rethink its co-operation with Libya's woefully dysfunctional coastguard and deploy more vessels where they are desperately needed."

Mr Dalhuisen stressed that "ultimately the only sustainable and humane way to reduce the numbers risking such horrific journeys is to open more safe and legal routes for migrants and refugees to reach Europe".

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published5 July 2017

- Published19 April 2017

- Published23 April 2017

- Published29 November 2016