Catalonia referendum defies Spanish obstruction

- Published

Students have declared a pro-independence "strike"

A nation, a Spanish region, an aspiring independent state: however you define it, Catalonia has become a byword in Spain for controversy and political conflict.

Now, the deadlock between Catalonia's devolved government, which wants independence, and Spain's central government, which has always ruled out a vote on the issue, has reached a critical moment.

There is the surreal.

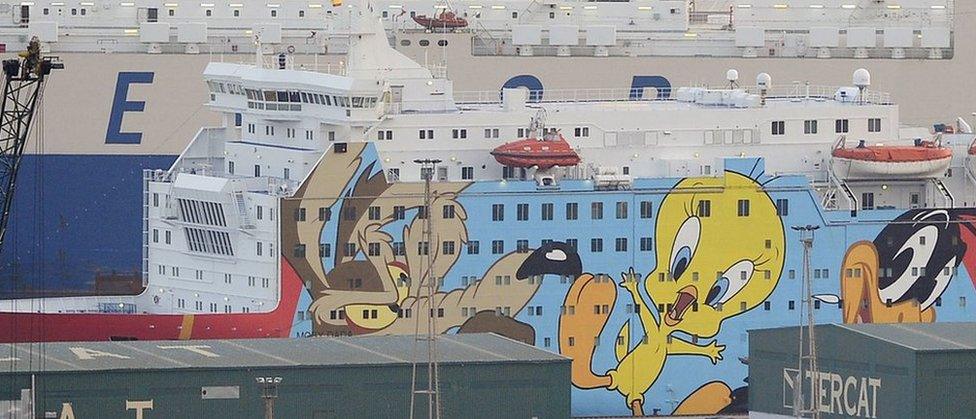

Tweetie Pie, the yellow Warner Bros cartoon bird known here as Piolín, adorns a cruise ship parked in Barcelona port. There are no tourists on board the huge floating hotel, just thousands of national Spanish police.

This ship, decorated bizarrely with cartoon character Tweetie Pie, is one of three chartered to house extra Spanish police

But there is an underlying and deadly serious message, too.

The boat's occupants are the guardians of Spanish territorial integrity. No-one questions where their loyalties lie.

Then there is the confusing.

Catalonia's government, or Generalitat as it is known locally, promises the vote will happen. However, a proper election campaign has been strikingly absent.

With children back at home for the weekend will schools quickly turn into voting stations, or will they remain closed?

And there is the downright baffling.

Catalonia's own police force, Mossos d'Esquadra, in theory should - if they follow the letter of Spanish law - work alongside national Spanish police and stop the vote from happening.

But it is the Mossos' colleagues and friends at the Generalitat who are keeping the pro-independence dream of a referendum alive.

The vote has stoked tension between Spain's Guardia Civil (L) and the Catalan Mossos d'Esquadra

Catalan police are stuck between a rock of Spanish court orders to stop the vote and a hard place of Catalan nationalist desires for it to go ahead.

If police physically stop people from voting, will this maintain public order or encourage trouble on the streets?

Fearing a backlash, the Spanish government has stopped short of suspending the powers of the Catalan government. But it has tightened its grip on Catalonia's finances.

In such uncharted waters, opinion polls about both independence and the idea of a vote suddenly feel outdated.

So, what I can offer are my perceptions based on the many people I have met in Catalonia over the past month, and during the four years when I lived in Spain, when Catalan nationalism evolved into a potent force.

For the record, this is anecdotal evidence, not scientific political data.

First, an army-sized, highly motivated chunk of Catalan society will at least try to vote on Sunday.

The chaotic nature of Sunday's poll means many No-supporters will stay away.

And so a majority of those who turn out will almost certainly be impassioned supporters of independence.

The opinions of these people have been well documented on the BBC over the past two weeks.

Fed up with Madrid

Others, like Silvia Gomez, who has family from two other Spanish regions, Andalucía and Aragón, admit that giving up 38 years of Spanish nationality would be a difficult call.

However she is tempted to vote Yes, for the same reasons as Cristina Caparros, who designs boats in Barcelona's port.

Cristina inclines towards independence because she disapproves of Spain's centre-right Popular Party government.

"I don't want to belong to this country any more… I think we can make a better, new country," she told me.

Why some Catalans want independence

I suggested to Spanish Education Minister Iñigo Mendez de Vigo that the stubborn negotiating tactics of his government, and sometimes less-than-diplomatic language on the Catalan issue, had driven more people into the pro-independence camp.

Past corruption cases, linked to his party, appeared to add fuel to an already-burning fire.

He simply ruled out any possibility of a legitimate Catalan vote on Sunday.

"In order to hold a referendum you need the ballot, an administrative organisation - nothing exists. So there will be no [public] consultation on Sunday," he told me.

"There isn't a consensus in order to change the Spanish constitution, so this is why the Catalan government goes unilaterally.

"To dance the tango you need two and in this case the Spanish government was always ready to talk, but they didn't want to dance. They only wanted to do things unilaterally and this is what the Spanish government will not accept."

Wary of split

There is another large, quieter and more ill-defined section of Catalan society, within which people have more nuanced opinions.

Fisherman Luis Talló, 54, has always considered himself "very Catalan, but not pro-independence".

But he is still demanding that the Spanish government allow a proper referendum.

His colleague, José González, who buys seafood in bulk straight from the boats, says his and other families are so split on the issue that it is no longer a comfortable topic at the dinner table.

Originally from Málaga in the south of Spain, he has lived in Barcelona for 66 years.

He is one of many people I have met in recent weeks favouring a referendum "done correctly" - but not the type of vote expected to take place on Sunday.

José says he protested and voted in a referendum in favour of more autonomy for Catalonia, before Spain's courts blocked the initiative, at the behest of the Popular Party, in 2010.

But he blames the pro-independence movement for "dividing Catalan society".

"If we want to stay friends, we cannot talk about politics anymore."