Catalan referendum: Who will move next in Spain's crisis?

- Published

Catalan leaders say 42% of voters turned out for Sunday's banned referendum

Spain's complicated relationship with the region of Catalonia is heading for the unknown.

After violence by Spanish police, a declaration of independence by Catalonia's regional government seems more likely than ever before.

Given the chaotic nature of the vote, the turnout and voting figures should be taken with a pinch of salt.

The government in Madrid is holding talks with Spain's political leaders to discuss a response to the biggest political crisis this country has seen in decades.

But the images of voters being physically attacked by Spanish police yesterday has emboldened the Catalan government, and the wider pro-independence movement.

It thinks it now has a stronger mandate to possibly declare independence from Spain, without the consent of Madrid.

Voters attempt to stop police seizing ballots. Some shouted: "We will vote! We are peaceful people"

It knows that the pictures of violence have been beamed around the world.

For now the pro-independence camp, which includes the Catalan government, is catching its breath.

Its leaders are meeting and working out their next move.

Before the vote, Catalan President Carles Puigdemont insisted to me that even if there was a Yes vote in Sunday's disputed referendum, his first option would be to sit down at the negotiating table and talk.

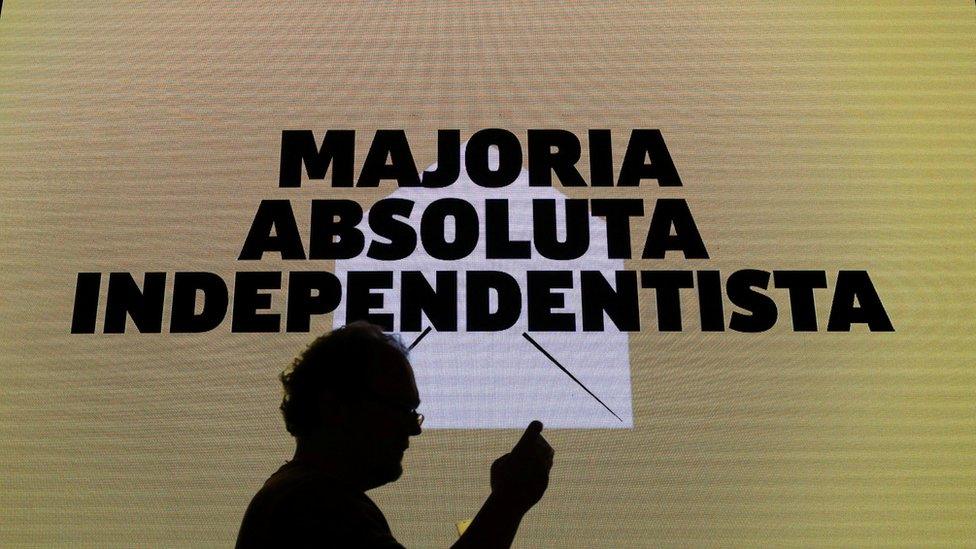

People celebrate after the closing of polling stations

Trying to force Madrid's hand to allow a legally binding, recognised referendum is still what the pro-independence camp want.

However Catalan and Spanish government officials have had five years to talk, and all it has brought is division and dispute.

Any decision to unilaterally declare independence would be put to a vote in Catalonia's parliament.

An opponent of independence holds a copy of the Spanish Constitution in Catalan during a protest against the Catalan referendum

But that is a volatile scenario, and Madrid might move first.

One number in the Spanish government's mind is 155.

It's the article of the Spanish constitution, which if invoked, would suspend the powers of the Generalitat, as Catalonia's devolved administration is called.

In theory, that would mean Catalonia's regional police, who sat back and allowed the vote yesterday, and sometimes sided with voters, would be directly controlled by the Spanish interior ministry.

Mariano Rajoy's government decided not to opt for the 155 option in the run-up to yesterday's poll, which Spanish courts have ruled to be illegal. On Monday they threatened to use it if any further move were made towards independence.

Officials in Madrid had earlier probably decided not to risk pouring fuel on the fire.

However, the violent tactics of the Spanish police on Sunday appear to have done exactly that.

One official in Madrid privately told me that Mr Puigdemont, Catalonia's leader, would not be arrested. And yet Madrid might want to pre-empt a declaration of independence.

The prime minister will meet the Spanish Socialist leader Pedro Sánchez on Monday.

The two leaders rarely see eye to eye but the Spanish government wants to present a united front.

At stake is the very existence of the Spanish state as we know it.

The Spanish political dimension in this also can't be ignored.

Spain's ruling Popular Party normally wins only a small proportion of the vote in Catalonia but it knows that a large part of Catalan society is vehemently opposed to independence.

Its general position of opposing a referendum has widespread popular support across Spain, even if many would have been outraged by Sunday's violence.

National Spanish public opinion will weigh on how the Spanish government acts.

- Published15 September 2017

- Published1 October 2017

- Published30 September 2017

- Published18 October 2019

- Published30 September 2017