Catalan crisis: Two views about independence

- Published

Tensions are running high in Spain in anticipation of a possible declaration of independence by the Catalan government. On 1 October, 43% of Catalans voted in a referendum, which the Spanish government declared illegal then tried to suppress by force.

The final results from the outlawed poll show 90% of the 2.3m people who voted backed independence.

There has been a big focus on relations between the government of Mariano Rajoy and the Catalan regional government. But what about relations within Catalonia itself, between people who are pro- and anti-independence?

Support for independence among Catalans isn't unanimous: some just wanted greater autonomy, while others are fearful of the economic and political impact of a split from Spain. These are the thoughts of two prominent Catalans, with different perspectives on the crisis.

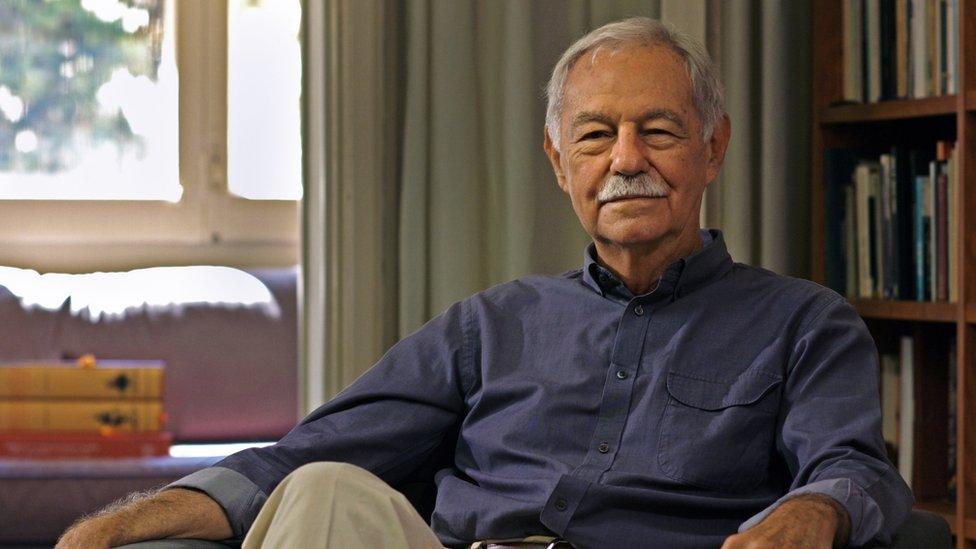

Eduardo Mendoza is one of Spain's most celebrated literary figures, a Catalan who doesn't support independence. He was awarded the prestigious Cervantes Prize for literature and wrote An Englishman in Madrid, among other novels. He grew up under Gen Franco, and says that the younger generation are wrong to draw parallels with the Francoist era.

"I think it is false to compare the current Spanish government with Franco. We live in a democracy: it's very imperfect. I don't like our government - I think most of our politicians should go to prison and many more burn in hell.

"But we live in a democracy, we cannot deny that. You can say anything you want, you can go wherever you want. To compare the Spanish government with Franco is to not have a memory or to be too young.

"People are falling out. It's very difficult to go back on this. It's lost forever, I think. Years ago I had friends who were pro-independence and others who were not. We never discussed the question of Catalan independence because we knew the arguments one way or another.

Protesters wave Spanish flags at a demonstration defending unity on Wednesday

"Now the divide is absolute. People don't talk to each other, even families are divided. Brothers and sisters and fathers and sons don't talk any more or they fight all the time. This is very sad because I don't think it will heal for quite a long time.

"Do we have an identity? I don't know. I think today everybody's identity is his or her iPhone. There is no national identity as such.

More on the Catalan crisis

"I think it's been a snowball effect. There was this dissatisfaction and with the economic crisis this increased. The Catalan government has previously used this dissatisfaction to blame Madrid and get away with anything.

"So the Spanish government didn't pay any attention - they didn't try to talk, they didn't look for peaceful solutions. So this 15% [support for independence] increased to 25, then 45 because the Spanish government has been deaf and dumb."

Monica Terribas presents the morning news programme on Radio Catalonia, the region's public radio station. She is pro-independence. She says there has been a new energy around the independence movement over the past seven years, partly because of the response of the Spanish state to its demands.

"Here in Catalonia there is a strong republican feeling because of the region's history. There is a feeling that we should organise society in a less hierarchical way and there are a lot of left-wing parties that are strong in Catalonia, much stronger than in the rest of Spain. I think there's a feeling that social rights and human rights and attention to the poor, attention to social movements will be represented in the building of this new society.

"The problem is that Madrid sees Spain as united and there is no way of discussing this. If there is a referendum, even if it's agreed with the state, you are seen as questioning Spanish sovereignty.

"Our society now is under pressure because there has been a violent reaction against polling stations on 1 October. This is the important thing: when you use violence, people are afraid, people don't think properly.

"The state should think carefully about using violence to solve political problems and the international community should be very strong when it sees a democratic state in the European Union doing these things. We aren't seeing an international reaction against that.

"And this can affect families - of course we are all talking about it. It is our future, our lives.

"I'm convinced now that if Spain agreed to hold a formal referendum of self-determination with Catalonia and they ran a campaign saying how wonderful it is to be part of Spain, a significant portion of people now voting in favour of independence would change their minds."

What's clear from these two views is that Spain is in the midst of a major constitutional crisis that could divide both the wider country and Catalonia itself.

Though Spain's Prime Minister Rajoy has called the vote a "mockery" and has defended the police crackdown, both Monica Terribas and Eduardo Mendoza believe that the politicians in Madrid have handled the crisis badly.

But that's where their agreement ends. Monica sees a bright, bold future for an independent Catalan state, whereas Eduardo sees a rupture that will be difficult to heal.

The Briefing Room was on BBC Radio 4 on Thursday, 5 October. You can listen online or download the programme podcast.

- Published5 October 2017

- Published5 October 2017

- Published26 March 2018

- Published22 December 2017

- Published3 October 2017

- Published3 October 2017