What should happen to IS fighters in Syria and Iraq?

- Published

How should the international community treat the defeated fighters of so-called Islamic State?

Countries must remember "our shared humanity" when dealing with captured fighters from so-called Islamic State, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

At a briefing in Geneva, the ICRC's deputy director for the Middle East, Patrick Hamilton, insisted that international law on the treatment of combatants must be followed, and rejected calls for the "annihilation" of fighters.

He acknowledged that the campaign against IS had left "huge devastation in its wake", with "catastrophic humanitarian consequences".

But while Mr Hamilton's remarks did touch on the appalling suffering of civilians who have had to live through the brutal regime of IS in Mosul or Raqqa - and the bloody battles for those cities - his focus was the future treatment of IS fighters, including those who travelled to Syria and Iraq from other countries.

The ICRC is already visiting more than 1,300 women and children of several dozen nationalities detained near Mosul.

They are believed to be the families of foreign fighters. As the coalition against IS gains more ground, more and more IS fighters and their families are expected to be captured.

So what should happen to them?

The ICRC, said Patrick Hamilton, was concerned about a "public discourse… on the desirability of annihilating those enemies still standing", and he warned against treating the fighters as "if they were outside our shared humanity".

'Dehumanising rhetoric'

He did not identify specific names of those carrying on such a discourse.

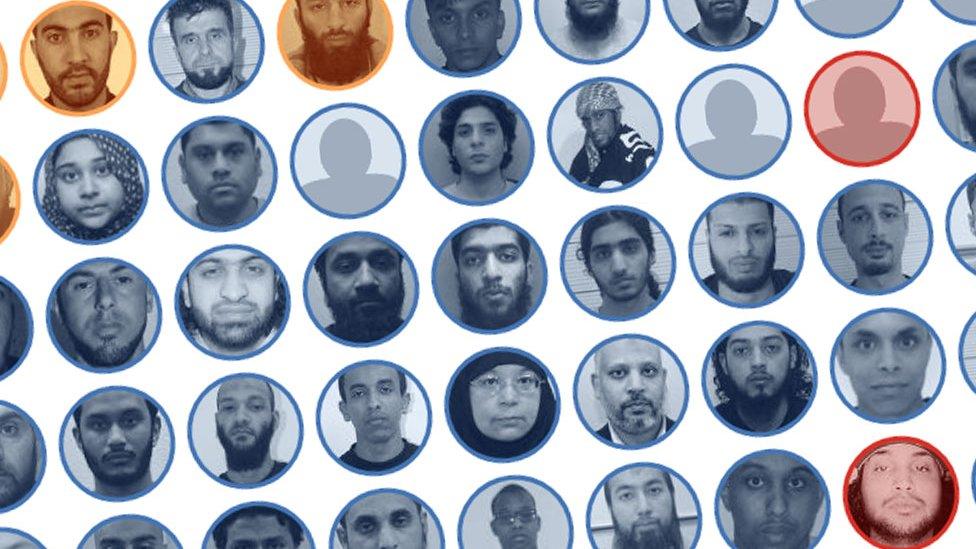

But when Mr Hamilton warned about "dehumanising rhetoric", he was probably referring to comments made by a number of Western politicians - including Rory Stewart, minister of state at the UK's foreign office - who recently said that UK citizens fighting for IS were a "serious danger to us".

"Unfortunately," he said, "the only way of dealing with them will be, in almost every case, to kill them."

At least 800 people from the UK have travelled to support or fight for jihadist organisations in Syria and Iraq

The French Defence Minister Florence Parly has also suggested that if IS fighters "perish in this fight, I would say that's for the best".

Brett McGurk, the US envoy to the coalition against IS, has said the coalition wants to ensure that foreign fighters "die here in Syria".

The comments from politicians may find a good deal of sympathy among voters.

Citizens and survivors of terror attacks in Paris, London or New York are understandably nervous about the prospect of individuals who joined IS returning home once the battle for the caliphate is lost.

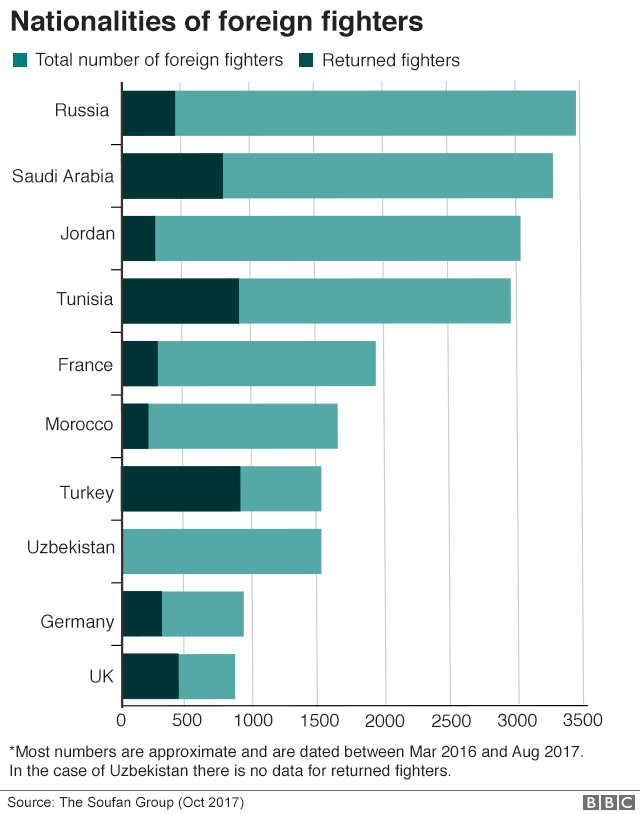

An estimated 30,000 foreign fighters are believed to have joined IS.

The security services view even a few hundred returning to Europe as a huge challenge: putting them in jail risks further radicalisation but allowing them to go free will almost certainly involve the police in round-the-clock surveillance work.

Many may struggle to identify any "shared humanity" with people whose ideology appears to include enslaving women, decapitating prisoners or driving trucks into crowds of tourists.

'Hors de combat'

But at the ICRC, the guardian of the Geneva Conventions, the mood is different. "Exceptional crimes do not justify exceptions to the law," said Patrick Hamilton.

In his view, any fighter "left standing" must be captured, detained, and, if crimes are suspected, brought to justice in the usual way.

Agnes Callamard, the UN's special rapporteur on extra-judicial, summary or arbitrary executions, shares the ICRC's concerns.

The UN's Agnes Callamard is also concerned about any desire to circumvent due process

She believes the current rhetoric focusing specifically on IS is "problematic". "In Syria and Iraq," she argues, "vast numbers of atrocities have been committed, by all sides - why single one out?"

People who are not actually fighting, she explains, are "hors de combat" - or "out of action" - and international law is very clear about how they should be treated.

She agrees with the ICRC that there should be no exceptions to this, and that there should be no arbitrary killing just because someone is believed to be a member of IS.

'Transparent process'

On a practical level, both Agnes Callamard and Reed Brody of Human Rights Watch fear that the apparent desire, as expressed by US President Donald Trump, to "annihilate Islamic State" could, if really carried out, destroy valuable evidence of war crimes.

"In terms of uncovering the truth and ensuring the victims or their relatives get justice," said Ms Callamard, "that can only be done through an open and transparent judicial process."

Raqqa has been devastated by three years of IS rule and the action to recapture the city

Mr Brody agrees that returning IS fighters present "challenges", but argues they also offer "opportunities".

He talks of the possibility of finding a way "to work with some of these former fighters to find out all we can about how Isis operates, and even to build criminal cases against high-ranking Isis officials who have been involved in war crimes and other atrocities".

"We have a right to know," adds Ms Callamard. "For history, how IS operated, who funded them. All of this is crucial information."

Winning the peace

Despite their apparent contradiction, underlying both the comments made by Western politicians and the pleas for humanity from the ICRC and others is a common desire for peace, both in the Middle East and on our city streets.

Eradication of a group that has caused so much horror may be an attractive solution, but the ICRC views it as short-sighted, as well as illegal under international law.

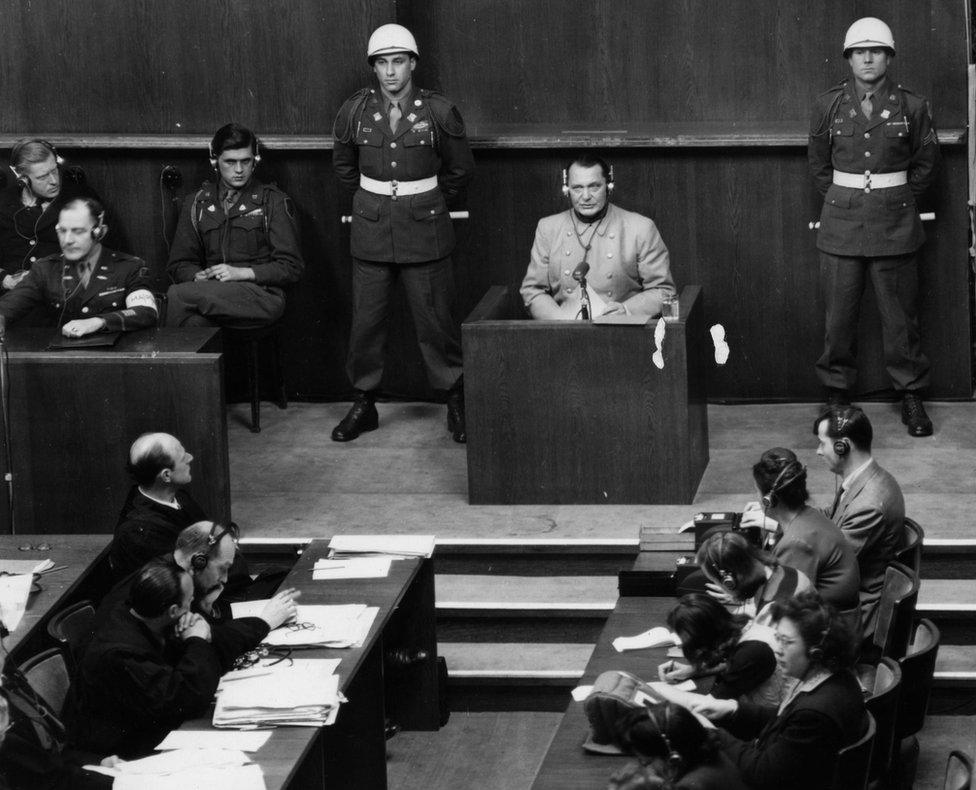

Nazi leader Hermann Goering was sentenced to death for crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg trials in 1946

"How a conflict is fought and brought to an end [is] important to future peace," Patrick Hamilton points out. "Talk of annihilation or extermination risks perpetuating the conflict."

"Our justice system is predicated on the fact that even the worst perpetrators… should have their day in court, for all to see," says Agnes Callamard.

And, she points out, we have had the vision and the energy to bring the perpetrators of history's most horrific crimes to justice in the past.

"We did it after World War Two [with the Nuremberg trials]. We did not have a choice then, and we do not have a choice now."

- Published24 October 2017

- Published23 October 2017

- Published23 October 2017

- Published17 October 2017

- Published11 September 2017

- Published2 September 2017

- Published5 August 2017