Inside the Iraqi courts sentencing IS suspects to death

- Published

Thousands of IS cases are being tried in courts like Nineveh Criminal Court in Qaraqosh (above)

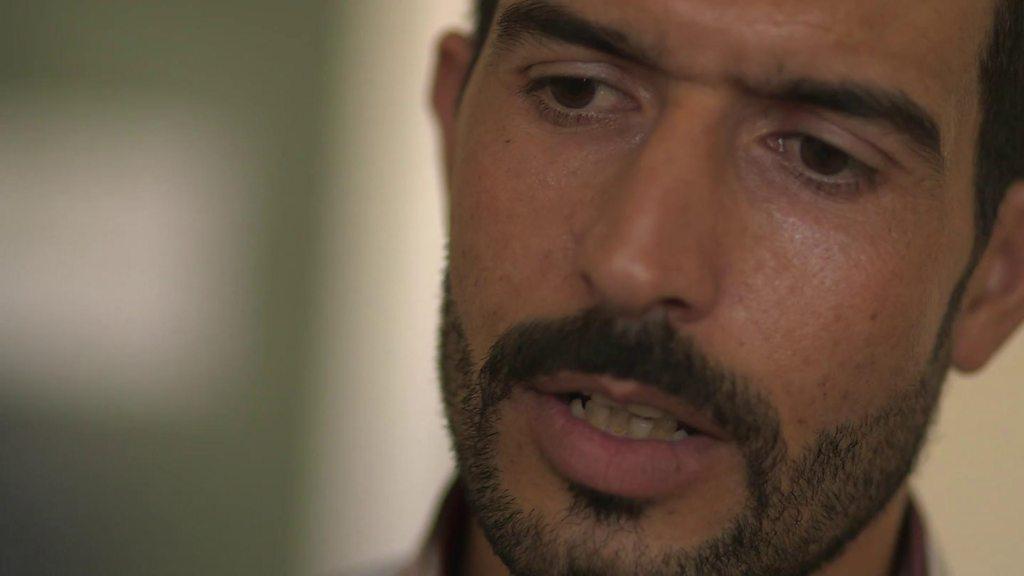

A young man wearing a shabby, brown prisoner's outfit stands before three black-robed judges in a tiny, provincial courtroom, shaking nervously.

After sipping some water, he confirms his name: Abdullah Hussein. He is accused of fighting for so-called Islamic State (IS).

"The decision of the court has been taken according to articles 2 and 3 of the 2005 Counterterrorism Law," states the judge. "Death by hanging."

And then Hussein - who, like many suspects here, was picked up on the Mosul frontline - breaks down crying.

As IS is defeated on the battlefields of northern Iraq, some 3,000 suspected group members or collaborators are waiting to be prosecuted in Iraqi courts. Usually there are at least 50 hearings a day.

IS fighters have been killed or captured amid a recent string of defeats

For security reasons, most are sent to two courthouses in this mainly Christian town, 30km (19 miles) south-east of Mosul, retaken by US-backed Iraqi forces in October.

Some human rights campaigners have criticised the system but top Iraqi judges insist it is playing a vital role in restoring law and order.

I was allowed to sit in on some of their trials.

Court confession

The next defendant, Khalil Hamada, is 21 and more talkative. He comes from a town held by IS for two years, and recalls seeking out its local recruiter.

"I went by myself, nobody forced me. A lot of us joined," he says.

"How did you join? What oath did you take?" the judge asks.

"I can't remember the sentences exactly," Mr Hamada replies. "But I swore loyalty to [IS chief] Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and the caliphate."

The Iraqi Christian ghost town

He goes on to recount how he did training with IS - in Sharia law, bodybuilding and using weapons.

But he tells the court he became "just a cook" - before admitting he was also one of six guards, "armed with Kalashnikovs" at an IS base.

He was paid about $150 dollars (£120) a month.

When the judge summarises his story, Mr Hamada nods, "Yes, it's true". A woman prosecutor then speaks and - albeit briefly - a state-appointed defence lawyer.

Like Abdullah Hussein, Khalil Hamada gets the death penalty.

He is told he can appeal and that a higher court in Baghdad makes final rulings.

However, his look of resignation suggests he knows this is little more than a formality.

'Sending a message'

During fighting in Mosul, Human Rights Watch (HRW) found evidence that some Iraqi soldiers were executing suspected IS members instead of sending them to trial.

It said men and boys fleeing the city were ill-treated, tortured and killed. Iraq's prime minister has since admitted there were "clear violations", external.

Now HRW says it has "serious concerns" about the quality of defence in cases being heard at the Nineveh Criminal Court in Qaraqosh.

The ancient Christian town of Qaraqosh was held by IS for two years

But Chief Judge Salam Nouri insists his court acts professionally and does an essential job.

"It sends a message to the people that the courts are the highest power and that the Iraqi government is back in control," he says.

"The judge remains neutral," says Justice Younis Jameeli, head of the Investigations Court, which has been temporarily set up in a large, family house.

He points out that IS targeted the judiciary in Mosul and says 15 of his colleagues were killed.

"Each of us lost family members and had homes destroyed but when a suspect appears before us, we treat him according to the law," he goes on.

Thousands of Christians fled and others were killed by IS

When I ask Judge Jameeli about evidence, he has a glint in his eye. "You know IS are helping us convict them," he declares, reaching for a file in the stack on his desk.

Inside there is further proof that IS are not some disorderly militia; they meant to function as a state. It is a spreadsheet, printed off from a computer and recovered by Iraqi intelligence.

Each of the 196 rows neatly identifies an IS member - his full name and address, job and a photograph.

Culpability questions

With real fears that jihadists will try to blend back into the Iraqi population, the hope is that prosecutions can stop IS re-emerging as an insurgent group and prevent reprisals.

Outside the court, I meet Muwafaq who has come from Mosul to make an inquiry. He tells me his neighbour, who joined IS, burnt down his home. "I hope he gets to court before I see him," he says.

But others allege their loved ones were wrongly arrested.

Law professor Ali Alhadidy describes how he had to go into hiding when IS arrived

One woman claims her husband, detained two months ago, has mental health problems.

A father says his son was "a regular guy selling vegetables from a cart" - not part of IS.

Talking to them, it is clear that judging exactly who was a collaborator is a tricky business; it is hard to tell whether some locals did what they had to just to survive or whether they bought into extremist IS ideology.

As court proceedings end for the day, armed guards march a column of prisoners out the gates, their heads down.

Iraqi Christians returning to villages destroyed by IS

The streets of Qaraqosh, all around, are virtually deserted.

Three years ago tens of thousands of residents fled this mostly Christian town as IS advanced and very few have moved back.

Now Qaraqosh - with its desecrated churches - bears testimony to the barbarity of IS and just how hard it will be for ordinary Iraqis to rebuild their lives.

- Published29 August 2017

- Published18 August 2017

- Published18 August 2017

- Published1 May 2017

- Published17 October 2017

- Published10 July 2017

- Published22 June 2017

- Published29 June 2017