The children trapped by Albania's blood feuds

- Published

It is said that revenge is a dish best served cold and in Albania it can be served very cold indeed. Disputes known as blood feuds can span generations, sucking in descendants who had nothing to do with the original insult or murder.

Though they have a long history, blood feuds remain potent today, with 68 families in the Shkodra region of northern Albania currently unable to leave their homes because of them.

We visited Niko, a 13-year-old boy, in his tiny hamlet in northern Albania. Niko is said to be "in blood", in other words, under threat of death for supposed "crimes" committed before he was even born.

Niko lives with his elderly grandparents and is in danger every time he leaves his home. Dozens of others families in the northern Shkodra region of Albania also live virtual self-imposed house arrest in fear of their lives.

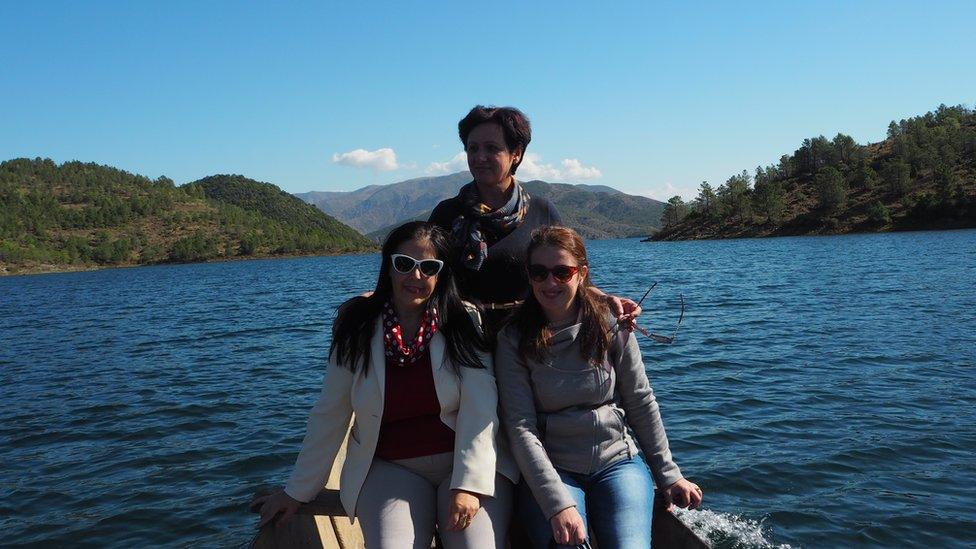

Three teachers on a boat going to visit Niko

We were taken by road and boat to visit Niko in his isolated community by his teacher Liljana Luani. Mrs Luani specialises in teaching "in blood children" at their homes. The blood feud means they cannot leave their homes, even to go to school.

The rules governing blood feuds have long been codified in a book of laws, called the Kanun, that dates back to the 15th Century. The Kanun helped to bring order to the lives of tribes in northern Albania, particularly during its incorporation in the Ottoman Empire.

Albania's blood feuds

"Gjakmarrja" means blood-taking: the blood feud. "Hakmarrja" is the obligation to take life to right an earlier wrong, to salvage honour.

Oral laws governing the blood feud go as far back as the Bronze Age. Kanun dates to the late 15th Century.

The Kanun is divided into 12 sections and helped regulate life for tribes in northern Albania.

1945-1991: Communist dictatorship suppressed Kanun and its code of honour. Participants in blood feuds were executed or imprisoned in labour camps.

1997: Economic crisis caused by pyramid schemes led to widespread social disorder. The Kanun makes a come-back.

Albanian government reforms state institutions and courts and hopes this will lead to decline in blood feuds.

Police arrest feud participants and investigate feud murders, bringing culprits to court.

But Mrs Luani said the Kanun was often abused by those involved in blood feuds.

"If they follow the rules of Kanun... they would not kill children and women. But nowadays neither the Kanun nor the laws of the state are being followed," she explained.

"It has happened that there have been women killed and children killed. I think the state law enforcement authorities should do more and that they are not working properly."

Niko is being brought up by his grandmother

The blood feud involving Niko's family began shortly after the deep economic crisis in Albania caused by the collapse of so-called pyramid selling schemes. The chaos led to a collapse of trust in state institutions and the judiciary.

The family became entangled in a land dispute with a family in a nearby village. A member of his family killed one of the neighbours. This led to other feuds and disputes involving nearby communities.

Subsequently, neither of Niko's parents lives at the family home, leaving him to be brought up by his grandparents near the homes of the other families involved in the feud.

Mrs Luani told us that Niko knows little about the feud. "He hears other people talk about all the issues involved in the feud. And all he does is to stay there silent. But you can tell he's very angry. He knows that he is "in blood", as the expression goes, and that his life is in danger and that he has to be very careful."

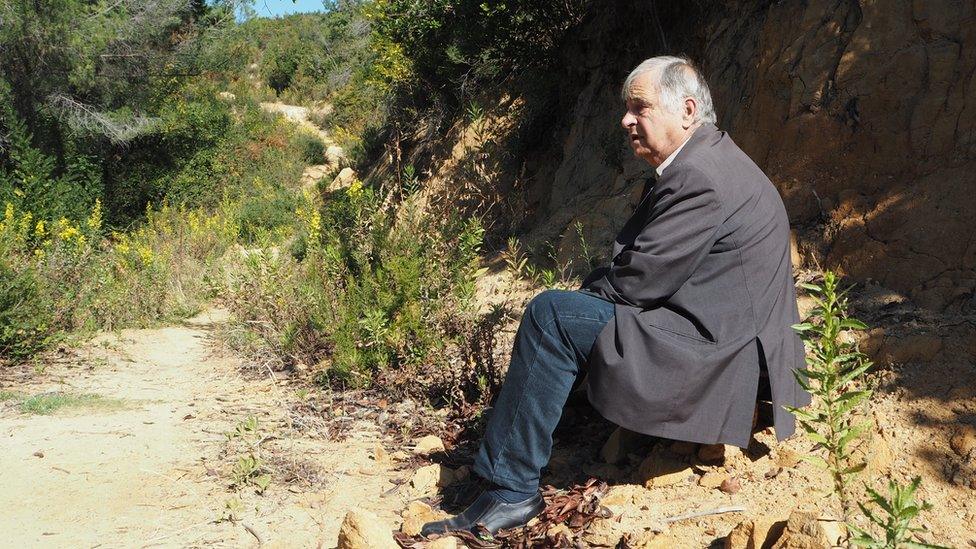

Colonel Gjovalin Loka, the police chief for the Shkodra region, said he was doing all he could to prevent and investigate blood feuds.

Liljana Luani with Niko

"We have intensively investigated cases of possible murders as the result of blood feuds," he said. "And we have intervened upon receiving information that preparations were being made to breach the law."

Colonel Loka also complained that people were misusing the Kanun, adding: "Different people are interpreting it in ways that suit them. It's not being implemented properly.

"Besides, nowadays we do have the laws of the modern Albanian state - that are in accordance with European law - and the time is up for the Kanun. Its place now is only in the archives."

There is a consensus that the continuing reform of state and judicial institutions must succeed if the blood feud is to be eradicated from Albanian life.

Dr Olsi Lelaj, a researcher at the Institute of Social Anthropology and Art Studies in Tirana, Albania's capital city, said: "It's not a matter of having a strong state institution but rather of having a just state institution. It is a matter of justice and a justice that is collectively shared."

Meanwhile, Mrs Luani continues to worry about Niko's future.

"I think that this is a problem that can be solved by all of us. I also work hard with the parents, especially with the mothers of these children because the mothers are those who teach and pass on to their kids tolerance, forgiveness and how to forgive and let go and not to continue with the cycle of violence."

- Published28 June 2023

- Published1 November 2017