Catalan politicians struggle with Spanish prison regime

- Published

The Catalan politicians were jailed on 16 October

"We're in here with murderers," noted one of the imprisoned Catalan politicians with incredulity.

Once he realised this was his new home, he decided to get down to practicalities. He got hold of a basketball and looked for a game of prison hoops.

Eight men and women who once governed seven million Catalans are now having to ask their families to put money onto pre-paid cards in order to be able to buy a packet of biscuits from the prison store.

They are being held in two separate jails. A third prison, near Madrid, holds two prominent pro-independence activists: Jordi Sànchez, 53, and Jordi Cuixart, 42 (in a confusing feature of both Catalan society and this particular article, many Catalans are named Jordi, after the region's patron saint.)

The two are under investigation for sedition over a protest in September, in which a crowd blocked Civil Guard officers inside a building in Barcelona.

"When they arrived in the Soto del Real prison near Madrid, five or six prisoners shouted 'Long live Spain, Long live the Constitution.'" said Jordi Sànchez's lawyer, Jordi Pina, "Jordi Sànchez said to the guard 'Should I go in or not?' The guard told the prisoners to quieten down and he went in."

The two imprisoned activists have since been split up.

Jordi Sànchez, a round man who speaks in the measured tone of an academic, shares a cell with an older Peruvian inmate. Jordi Cuixart, whose long hair and ear-rings might allow him to pass as the leader of a rock band, bunks with an Irish prisoner.

Jordi Sànchez heads a leading pro-independence group

On Sundays, prisoners from all wings in Soto del Real are allowed to come together for a church service. This can prove to be the most dangerous time. During one recent Mass, attended by Jordi Sànchez, one prisoner stabbed another.

The two imprisoned activists are allowed daily visits from their lawyers - from whom they are separated by a glass barrier. Every Saturday, their families are allowed a 40-minute visit.

Jordi Cuixart's wife, Txell Bonet, gets up at 04:30 to take their six-month-old son on the train from Barcelona to see his father through the glass. "You want to talk about lots of things," she says, "but it's stressful, with the pressure of time, knowing it will be over."

Jordi Cuixart was also detained by Spain's High Court

Twice a month, the prisoners are allowed a three-hour family visit without a glass divide. This period of time is long enough for its participants to pick up the normal rhythm of family discussion and argument - which, paradoxically, cheers them a great deal.

The families are allowed to give the inmates winter clothes - particularly useful given the fact that the prison's heating is switched off at night. Prison food is described by one of their lawyers as horrendous ("I don't ask them for precise details," he said drily.)

Apart from that, the prisoners have a lot of free time. "Jordi Sànchez writes a lot," says his lawyer, "He reads. He receives about 100 letters a day."

Prison warders have to open each envelope in front of the prisoners, to check for contraband. The guards destroy letters which do not include the sender's name.

Txell Bonet recently gave her husband the book Walden by Henry David Thoreau, which details a man's attempt to learn self-reliance by living in a cabin in the woods.

The imprisonment of two prominent activists and eight former ministers is made more unusual by the fact that most of them are in the middle of a political campaign.

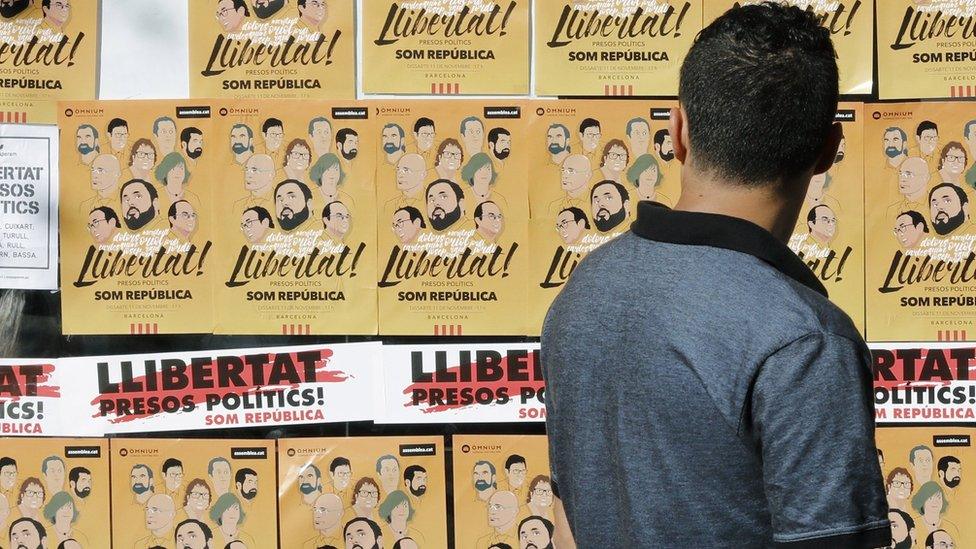

"Freedom" banners in reference to the jailed politicians were held during a protest last month

Seven of the eight imprisoned ministers are running for re-election to the Catalan parliament on 21 December. Jordi Sànchez, one of the two imprisoned activists, has decided to stand on a list with the former Catalan leader Carles Puigdemont. But he has struggled to find out who else he is running with.

"The prison authorities didn't let me give him the list of candidates," said his lawyer, Jordi Pina, "So I had to hold it up to the glass."

Imprisonment may create strain for the prisoners and their families - the teenage daughter of one of them cannot bring herself to speak to her father during allotted four-minute calls because it is too upsetting to get cut off - but it is a significant boost to their political standing.

The jailed politicians and activists have tapped into a long history of imprisonment and exile in Catalan politics.

"I think you can speak of the exiled and jailed politicians in the same sentence as Lluis Companys [Catalan leader jailed and executed in 1940] and Josep Taradellas [Catalan leader exiled between 1939-1977]," says Catalan historian Jordi Rabassa.

"I say this without agreeing with their political positions. They can be termed political prisoners."

A small town divided over independence

Some pro-independence Catalans are privately disappointed with what they consider to be the politicians' haphazard management of October's independence campaign.

But Spain's decision to imprison the former politicians, provides them with temporary immunity from recrimination.

"It's very difficult to criticise what those in prison have done, simply because they're behind bars," adds Jordi Rabassa.

Txell Bonet, Jordi Cuixart's wife: "He and I don't speak much of the future"

While extended imprisonment may be in their political interest, the activists and politicians are determined to win back their freedom as quickly as possible.

One lawyer has made sure there will be no reference to unilateral independence in the politicians' campaign manifestos, to prove to the Spanish courts that the prisoners are now obeying Spanish law.

The potential penalties are severe. If convicted of rebellion, the former cabinet ministers face up to 35 years in prison. The two activists, who face the lesser charge of sedition, face a maximum sentence of 10 years.

"He and I don't speak much of the future," says Jordi Cuixart's wife Txell Bonet, "but we always prepare for the worst. We don't get our hopes up."

- Published26 March 2018

- Published22 December 2017