How French 'Non' blocked UK in Europe

- Published

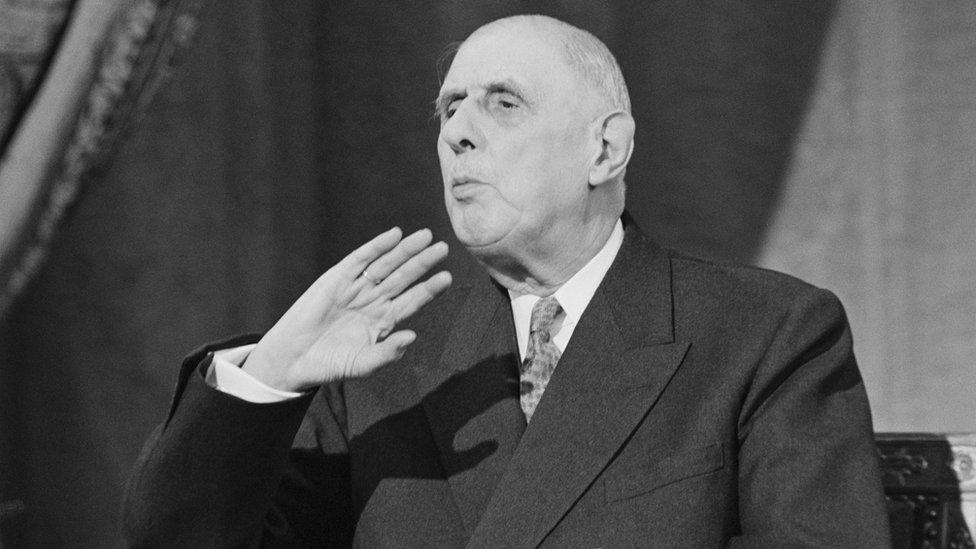

Charles de Gaulle in 1967: French "Non" to UK membership of the Common Market

In November 1967 the world was recovering from the "Summer of Love" - but not everyone was touched by a spirit of togetherness.

The BBC certainly did its bit, hosting the first live global satellite television programme linking the continents together, and offering the first glimpse of our connected future.

Even The Beatles played their part - appearing on the programme to perform All You Need Is Love. Ironically, after they fell out and grew apart, they couldn't agree on whether the song had been specially written for the show.

More ironically still, given the way events were unfolding in Paris, the track began with the opening bars of the French national anthem, The Marseillaise, presumably as a salute to internationalism.

In the French capital, President Charles de Gaulle was preparing to give his verdict on Britain's application to join the then Common Market, after long years of negotiation.

It may seem hard to imagine, at a time when the business of getting out of the EU dominates the headlines, but back then you could hardly pick up a newspaper without finding a story about the UK's desperate efforts to get in.

As far as I can discover, no-one thought to call it "Brexin". But that's what it was.

Heath the Europhile

Under the Conservatives in the early 1960s there had been a degree of passion in the project. Their chief negotiator Ted Heath was possibly the most Europhile politician in British history.

Ted Heath finally steered the UK into the Common Market in 1973

When Labour came to power in 1964 the new prime minister, Harold Wilson, didn't radiate the same degree of enthusiasm. But he was prepared to do a deal if the terms were right.

So he and his bibulous Foreign Secretary George Brown criss-crossed the continent, conducting talks with the governments of what were then the six member states.

Britain - then as now - was a problematic partner for Europe.

It had extensive international financial interests which were the legacy of empire - the pound was still a reserve currency. And there was the perennial, troubling closeness to the Americans - a perception that was rather unfair on Wilson, who behind the scenes had been struggling to keep Britain out of America's war in Vietnam.

But it was clear all along that, not for the first time in British history, the real problem was France.

Charles de Gaulle during a state visit to the UK in 1960

Charles de Gaulle carried with him an authority that no other elected politician of the 1960s could match.

When the French army was defeated by the invading Germans during World War Two he was politically unknown - an obscure officer.

Once he arrived in London though he made himself the living embodiment of French statehood and forced first Winston Churchill, and eventually the leaders of the other world powers, to accept him in the same terms.

He had already vetoed a first draft of Britain's membership application in 1963, and nothing had happened in the intervening four years to leave him better disposed to the UK.

Six nations signed the 1957 Treaty of Rome establishing the Common Market

Plenty of people in Britain felt the general couldn't forgive the British the burden of gratitude - the UK had sheltered, protected and rearmed him during the war, and treated him as a world leader long before he was ever elected.

He cut an extraordinary figure - gloomy and aquiline, with a face that suggested an affronted buzzard. He was a giant of a man but managed somehow always to make his civilian clothes look as though they were slightly too big for him.

There were no surprises in his address at the Elysée Palace on that November day 50 years ago.

He told his invited audience that the British view of European construction was characterised by a deep-seated hostility and that the UK would require a radical transformation if it were ever to be allowed to join the Common Market.

Anti-American mindset

The UK wrote an indignant reply to De Gaulle, knowing that the other members of the Common Market were all keen to see the UK join. But it was to no avail.

The UK's application for membership was not approved until the general fell from power, and he was dead before the UK actually joined.

Leave campaign, March 2016: The UK becomes the first nation to leave the EU

The question is of course whether Brexit proves that to some extent De Gaulle had a point - that the UK just wasn't a good fit for Europe.

I asked two leading politicians - one in the UK and one in France - how De Gaulle's decision looked to them both, in retrospect and at the time.

Edith Cresson, who went on to be French prime minister (the first woman to hold the post), was a young management consultant in 1967.

She is no fan of Brexit and wasn't a Gaullist either, but she concedes that the general may have had a point when he worried that the British would effectively act as American agents inside the Common Market.

"It was his personal decision. He had a lot of experience of the British and he always thought that they'd be on the Americans' side… so I don't think he believed that they'd play the game of Europe," she said.

"Formally they'd be in, but actually they'd always be with the Americans."

The veteran British Conservative Ken Clarke, who shared Ted Heath's passion for the European project, was disappointed by De Gaulle's decision and offers a rather less sympathetic analysis.

"De Gaulle was ferociously anti-American and pretty anti-Anglo-Saxon," he said.

"He modelled himself a little on Napoleon and wished to have a European Community which was dominated by France and steered by a Franco-German alliance, which was out of touch with the way the world was going. He was a great man, De Gaulle, but slightly unworldly. Sooner or later we were going to join because no-one had any alternative."

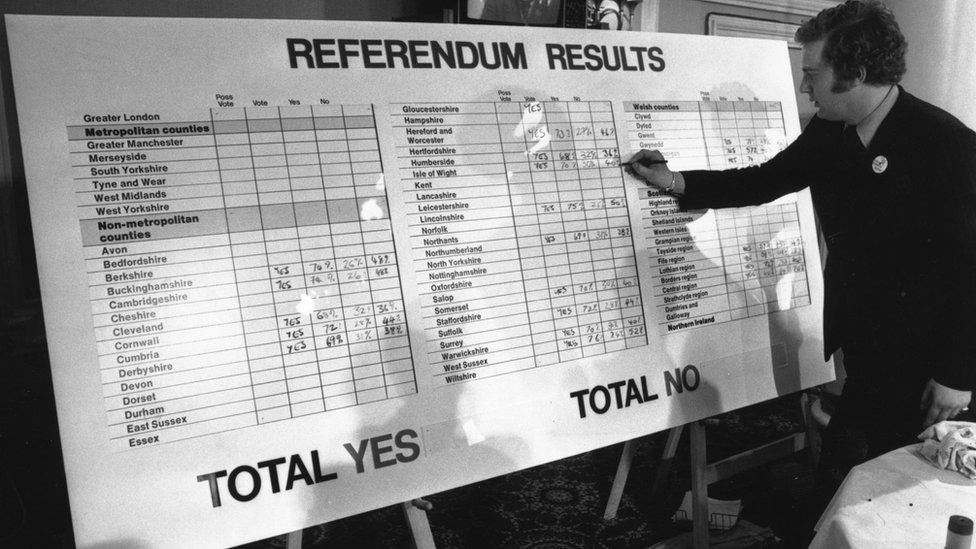

The UK backed continued membership of the European Economic Community in a referendum in 1975

It's worth noting of course in that context that De Gaulle's implacable opposition to "Brexin" didn't ultimately make any difference. Five years later a triumphant Ted Heath finally negotiated UK membership of the Common Market.

In many ways the concerns of the world of 1967 seem as remote as the concerns of ancient Rome: the Vietnam War, a formal government devaluation of the pound and a huge oil slick off the coast of Cornwall.

It's a sobering thought that the only issue that seems recognisable to us from the headlines of the period is the length and difficulty of negotiations over the UK's status in Europe.

Somehow the troubled nature of that relationship has endured - even as the world has changed around it.