Belgium ends 19th-Century telegram service

- Published

Belgium's telegram service is about to stop. Stop.

One hundred and seventy-one years after the first electrical message was transmitted down a line running alongside the railway between Brussels and Antwerp the final dispatch will be sent and received on 29 December.

The fact that this 19th-Century technology is still up and running in the age of Instagram and Snapchat may seem rather odd - especially when you consider that the UK, which invented the telegram in the 1830s, abandoned it as long ago as 1982.

The United States followed suit in 2006 and even India, which had been by far the world's biggest market for the telegram, finally closed its system down in 2013.

Just 10 businesses and a handful of individual customers have kept the Belgian system going until now. It has been chiefly used by bailiffs, who had need of a system which provided legal guarantees of dispatch and receipt.

The buyer can call up a telephone operator to spell out their message, which is then sent by post.

But with a "flash" telegram costing €23.75 (£21) for a basic 20 words, plus €0.90 for delivery in and around Brussels, it is not difficult to see why the system is struggling to survive in the age of unlimited texting on cheap mobile phone tariffs.

Brevity is key

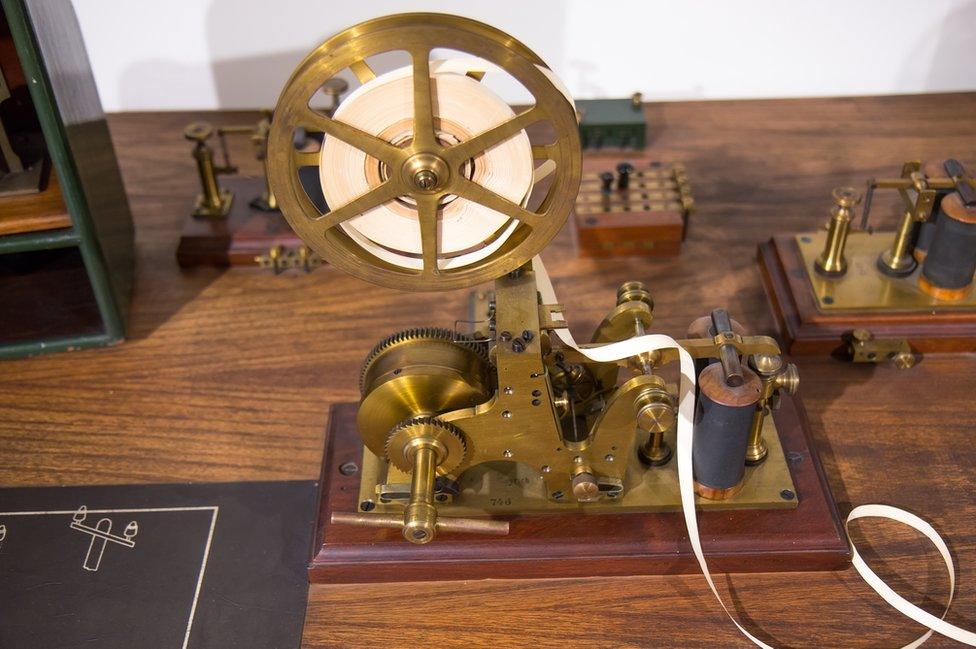

Before the invention of the telephone, the telegram was the first system that allowed the more-or-less instant transmission of electrical messages over long distances.

The electrical impulses from the sender's machine - Morse code became the commonest system - were translated into text at the receiving end, first by human operator and then eventually by machine.

The printed text was then delivered to the ultimate recipient - post offices all over the world employed armies of telegram boys on bicycles.

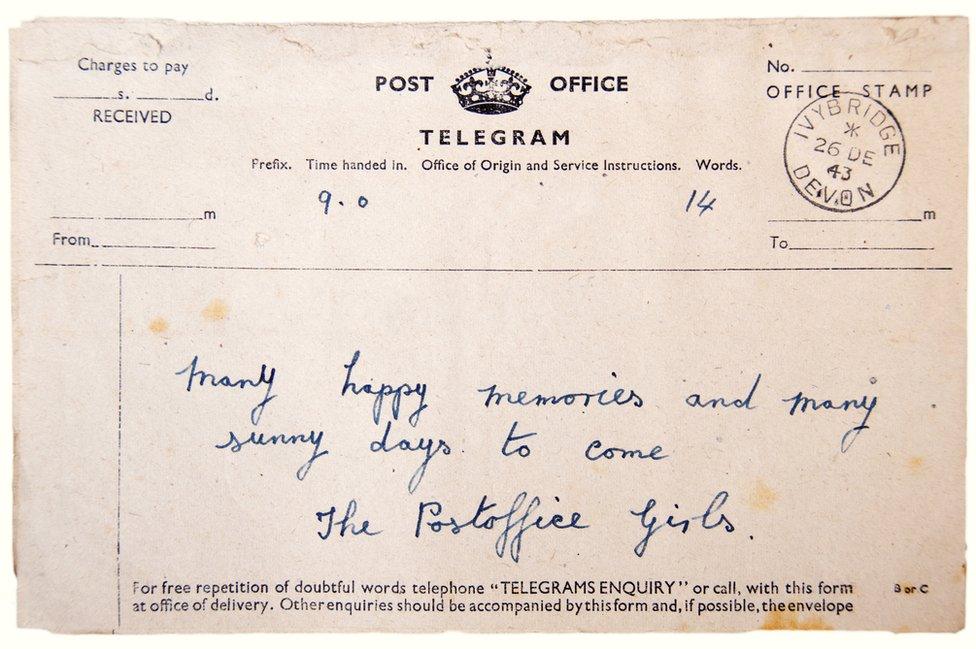

The technology created a certain style of writing - just like text messaging.

The use of the word "Stop" for example, often written out in full, originated from the need to tell the receiver when the end of a sentence had been reached.

And because telegrams were expensive - you paid per word - there was always pressure to come up with phrases that literally displayed economy of language.

Famous telegrams

Evelyn Waugh

When Evelyn Waugh was despatched to Africa to cover the war in Abyssinia for the Daily Mail in the 1930s he displayed the kind of linguistic ingenuity to be expected from a great English novelist. Finding it necessary to kill a story which said that an American nurse had been blown up in the town of Adowa, Waugh managed it in a message back to London consisting of just two words: "Nurse Unupblown"

No-one could rival Oscar Wilde for brevity. He is said to have once asked his publisher how a book was doing, by telegraphing simply "?". To which the publisher replied enigmatically "!"

When the British General Charles Napier conquered the fractious tribes of Sindh during the British conquest of the Indian subcontinent he was popularly rumoured to have celebrated the event with a one-word telegram back to the War Office in London. It said simply: "Peccavi" which is the Latin for 'I have sinned'. It later emerged the pun's true author was an English schoolgirl who submitted it to the satirical magazine Punch

The system was costly and labour-intensive for a start and began to feel outdated as more and more ordinary families acquired telephones.

But even as the telegram died out, it remained a part of popular culture.

No wedding scene in a Hollywood movie was complete for decades without a scene in which the best man read out the telegrams - humorous or cheeky or poignant - which guests who couldn't make the service had sent from afar.

In the UK any loyal subject reaching the age of 100 traditionally received a telegram from the monarch - a huge honour for the recipient.

And in the years when we are commemorating the 100th anniversary of the grim battles of the Great War it is only right to record that for decades the sight of a telegram boy coming up the path with a message was something to be dreaded in many countries.

The telegram was the chosen method by which the authorities informed grieving mothers and widows that husbands, sons or brothers were killed, injured or missing in action.

I've known widows who never forgot the agonising moments between the arrival of the delivery boy and the first reading of the words that began: "I regret to inform you".

So the world won't really change when Belgium finally pulls the plug on its telegram system, but it is another milestone in the long, slow death of a method of communication that once changed the world and which, in its glory days 100 years ago, seemed as though it would never stop. Stop.