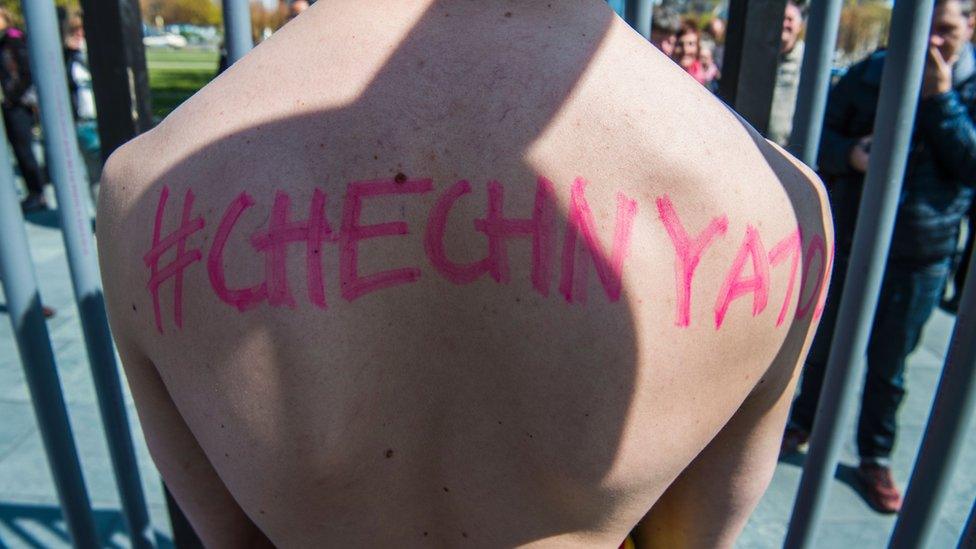

Chechnya gay rights activists 'make up nonsense for money' - Kadyrov

- Published

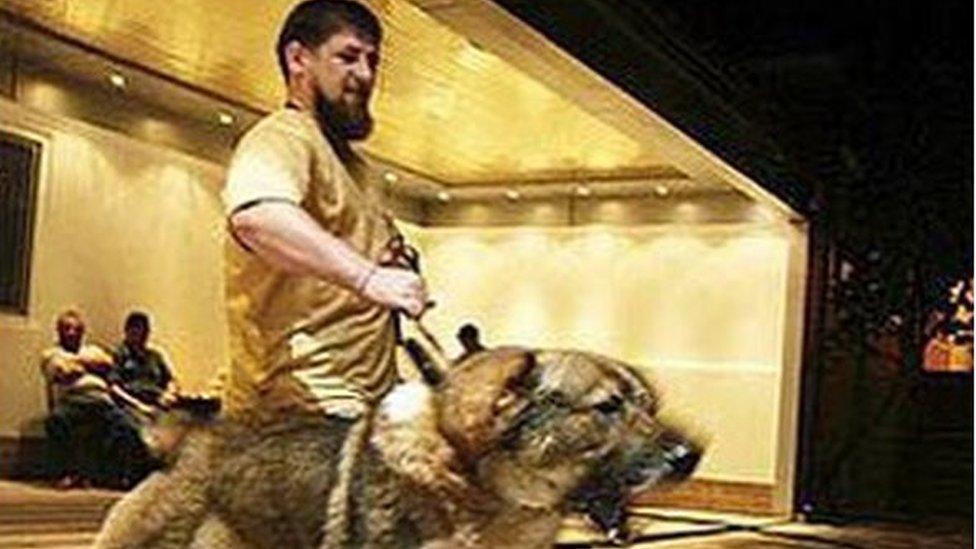

Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov is questioned by Sarah Rainsford on the region's human rights record

Ramzan Kadyrov arrived in the Caucasus mountains to rows of people applauding him furiously.

The leader of Chechnya had come for the official opening of the republic's first ski resort.

As he's notoriously hard to get near to, that's where I'd come too - to question him on his human rights record. That includes recent reports that gay men in Chechnya were detained and tortured.

The multi-million-dollar ski project is still far from finished, with only one short slope built.

Organisers had to truck in snow for the grand ceremony too, arriving moments before Ramzan Kadyrov's jeep roared up.

But those were not details to spoil his party. For the Chechen leader, the Veduchi resort is highly symbolic.

For years, these mountains were the stronghold of Islamic extremists. Before that, they were the base of separatists fighting to break away from Russia.

Ramzan Kadyrov was one of them - until he switched sides to battle the Islamists.

Now, fiercely loyal to President Vladimir Putin, he's largely left to run this Russian republic by his own rules.

That's brought allegations of abuse at the hands of his security forces, with claims of extrajudicial killing and illegal detentions.

It's why the US has now added Ramzan Kadyrov to a sanctions list.

Touring the facilities that Chechnya hopes can lure foreign tourists one day, Mr Kadyrov wanted to shrug off all such talk.

Mr Kadyrov arrives at the slope with his entourage

"You know who protects human rights here," he told me first, with a barking laugh. His awkward entourage laughed along with him.

I'd caught up with him as he jumped off the ski lift after its inaugural run. At the top of the slopes, he insisted that "not one person" in the republic commits human rights violations.

"That's all an invention by foreign agents who are paid a few kopecks" he told me. "So-called human rights activists make up all sorts of nonsense for money."

But last year, I met several Chechen men who gave horrific accounts of what happened to them.

One - who asked me to call him Ruslan - described being beaten and electrocuted, and held in a basement for over a week.

'Ruslan', a gay man who says he fled: "It's the extermination of gay men"

In deeply conservative Chechnya, he said it was punishment for being gay.

We spoke in a safe house after Ruslan had fled, one of dozens with similar stories. Many are now abroad, but those helping them say they're still hearing from new victims.

And now activists investigating abuses are being threatened themselves.

Last month, the head of the Chechen division of a human rights group - Memorial - was arrested. Oyub Titiyev is facing up to 10 years in prison after police discovered marijuana in his car.

Shortly after his detention, Mr Titiyev wrote an open letter to Vladimir Putin insisting that the drugs were planted.

"If I somehow confess my guilt… it will mean I have been forced through physical coercion or blackmail," he wrote.

The Memorial team had been checking reports of extrajudicial killings.

A group of men went missing after being taken away by security forces. It's thought they were suspected of links to extremists - but there were no charges, so nobody knows.

Memorial's research confirmed that 27 people had disappeared.

A senior member of Memorial, Oleg Orlov told me they had confirmed the detentions and when they occurred.

"We tried to follow up with legal procedures but the relatives were threatened and terrified. Perhaps that's the work that annoyed the authorities."

Just over a week after Oyub Titiyev was arrested, the group's office in neighbouring Ingushetia was torched. A car was set alight in Dagestan, and staff received threats.

"It's clear that after that anything could happen," Mr Orlov says, pointing out that Memorial is the last independent human rights groups still operating in Chechnya.

"It's very dangerous to work in Chechnya now."

A sign in Grozny, the Chechen capital, mirrors tourist slogans of other cities

Ramzan Kadyrov doesn't hide his contempt for human rights groups.

"Let them work somewhere else!" he told me, waving an arm for emphasis. "All those who defend human rights groups and the gays we supposedly have in the Chechen Republic are foreign agents.

"They've sold out their country, their people, their religion!"

As for Oyub Titiyev, the Chechen leader dismisses him as just another "drug addict" being detained.

When I try asking about claims of torture, Mr Kadyrov's security guards decide that's enough, and pull our camera away.

The Chechen strongman had come for a celebration, after all.

As darkness replaced the fog, there was live music and dancing on stage - then motorbike stunt riders flying through the sky over bright orange bursts of fire.

But human rights activists say events like this are just veneer. The mountains have been reclaimed from militants, but Chechnya is now ruled by fear.

Now Memorial itself is being forced to consider its future in the republic.

"With no human rights groups left, people will have no protection," Oleg Orlov warns.

"Anything at all could be done to them and there would be no-one to complain to. No-one to tell."

- Published17 October 2017

- Published16 May 2017

- Published7 September 2017

- Published21 April 2017

- Published28 August 2023

- Published16 December 2014

- Published11 April 2017

- Published21 May 2020

- Published20 January 2016

- Published29 April 2016

- Published13 August 2013