Germany’s coalition deal: The young activists hoping to derail the agreement

- Published

Michael Sachs and Anne-Marie Hovingh are SPD members with very different perspectives on a grand coalition with the centre-right

Germans could be going back to the polls if members of the Social Democrats vote against a new alliance with Angela Merkel's conservatives. The results will be announced on Sunday, and it's a decision that pits the party's old guard against the new, as Jenny Hill reports from Hamburg.

It's a delightful institution, the German kiosk - a place where you can post your parcels, buy basic provisions, read a newspaper and drink a beer.

On a Hamburg street corner, door closed against the winter chill, a cheerful shopkeeper hands over online deliveries to customers waiting under shelves crammed with bottles.

And in the corner, leaning against a makeshift table fashioned from beer crates, an old man and a young woman talk politics.

"The grand coalition that's just ended wasn't as bad as it was painted within the CDU, the SPD and the media," says Michael Sachs.

He's a lifelong member of Germany's centre-left Social Democrats (SPD) and sat on the regional government here. "We have high economic growth, low unemployment, a foreign policy which aims to create peace in the world. We don't have a Trump or a decision like Brexit."

As you might expect, Mr Sachs voted in favour of another grand coalition between the SPD and Angela Merkel's CDU/CSU bloc, describing another four years with the conservatives as "the best thing that could happen to us".

Across the table, Anne-Marie Hovingh, a 30-year-old SPD member, is horrified by the idea. "We can only debate properly in opposition. As soon as we're in government the inner party discourse is stifled," she says.

The ink's barely dry on a hard-won coalition agreement. It holds no incentive for this young party activist.

"We need to try to solve the problems of the century - one of which is the integration of refugees. If I read the coalition treaty, I can't see answers to that."

Waiting for a stable government

Nearly six months on, Germany is still talking about September's general election.

They are still waiting for the stable government Angela Merkel promised the country.

This coalition - with her old SPD allies - is her only realistic shot now at forming a government. A minority government is possible but it's considered unsustainable.

Mrs Merkel failed to build an alliance with the Green and liberal Free Democrat parties. If this deal falls apart, the spectre of fresh elections looms.

Mrs Merkel's future, it's said, now lies now in the hands of a chap called Kevin.

The 28-year-old leader of the SPD's youth wing, Kevin Kuehnert, has passionately led an internal revolt against the proposed new coalition.

Kevin Kuehnert leads the SPD's youth wing and is against a coalition with the centre-right

His supporters believe that their last term in Mrs Merkel's shadow damaged the party and that to reprise the role of wing man to her CDU/CSU union would finish it altogether.

The SPD leadership is in favour of the deal. It emphasises concessions won during coalition negotiations, such as the party claiming finance minister - a key post.

But the party's members are horribly divided and all 460,000 of them get the final say.

An ageing party

It's a struggle, broadly though not exclusively, divided along generational lines. The old guard against the new.

"We're an ageing party," says Anne-Marie, smiling across the table at Michael Sachs. "I don't want to insult anyone present but we have a lot of old men in the party.

"I'm the youngest regional parliament member and do you know who I have to fight against the hardest? My own people."

"I was young once too," Michael says. "I've been in the SPD in both opposition and government. It's a tradition in this party that, in opposition, the left wing and the young are given lots of freedom.

"It's the same for Labour in the UK. Once they join the government, they don't implement all those grand ideas."

Mr Schulz (C) resigned after leading the party to a disappointing general election result, with Andrea Nahles (L) taking over

The SPD's anthem rings rather hollow now.

Its opening lines - "when we walk, side by side" - belie the division and the confusion over its very identity.

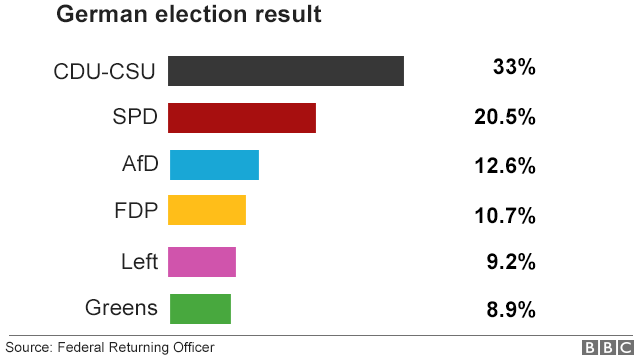

Its former leader Martin Schulz was supposed to take the party to a glorious election result. Instead he led them to one of the worst outcomes in its electoral history.

Many blame his indecision for the current crisis. First, he rejected another grand coalition. Then, he capitulated. He then ruled out taking a post in the new cabinet, only to announce he'd be foreign minister. He later abandoned that plan.

After his resignation last month, Andrea Nahles was appointed leader-designate. Once officially in the job, she'll have to reunite, rejuvenate and modernise the party.

An identity crisis?

The internal schism has laid waste to what were already dismal approval ratings.

The SPD is now virtually neck and neck with the far-right Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD) in the opinion polls.

Michael Sachs believes the problem is deep-rooted. He says a leadership crisis began when Gerhard Schröder, Germany's chancellor between 1998 and 2005, stepped down.

"The leaders don't know where they want to go. Which is why we have this crazy situation where the leadership has negotiated a grand coalition and at the end holds a referendum."

But the party, he continues, must navigate a different world, divided into those who benefit from globalisation and those who fall victim to its consequences.

"In the last few decades the old class society has disappeared. We don't have the blue collar workers who are trade unionists and, at the same time, Social Democrats."

"The world," Anne-Marie echoes, "has changed and we need new answers".

She and Michael finish their coffees, wrap up warm and prepare to leave the kiosk for the bitter cold outside.

Little unites the two factions of a party in the midst of a profound identity crisis.

Regardless of which emerges triumphant on Sunday, as Michael puts it, "there won't be any winners in this".

- Published9 February 2018

- Published7 February 2018

- Published7 February 2018

- Published22 January 2018