National Front: Whatever happened to France's far right?

- Published

Marine Le Pen was defeated in last year's presidential election by Emmanuel Macron

France's far-right National Front (FN) is voting this weekend on whether to allow a change of its name. Leader Marine Le Pen has said she wants a new name to reflect a "change in the nature" of the party.

Since losing to Emmanuel Macron in the presidential run-off last year, Ms Le Pen has lost voters, endured attacks from her father and seen the defection of some of the party's most important figures. Will a name change turn the FN's fortunes around?

The pastel buildings and sun-soaked palm trees of Cogolin give the square a tranquil, postcard feel.

This tiny Mediterranean town, nestled alongside Saint Tropez, is renowned for producing hand-made pipes. It is a place that values tradition and the old ways of life.

Cogolin chose Marine Le Pen over Emmanuel Macron by a clear margin but, almost a year on, her party seems to have lost momentum even here. Mayor Marc-Etienne Lansade quit the party after the election, disillusioned with both its economic policy and, he says, its chances of ever winning power.

Bystanders at the town's pétanque court said there was no clear opposition party in France now either.

"The left-right divide is dead," said one woman. "Political parties are no longer relevant, but they all have some good ideas: Marine Le Pen, [the far-left leader Jean-Luc] Mélenchon, and the others too."

The FN received almost 11 million votes in the election, presenting itself as the natural party of opposition to Mr Macron's liberal, internationalist vision. So why, since then, have more than a third of party members failed to pay their dues and several key figures quit?

Who is in, who is out

Florian Philippot, once the party's number two and popular with newer converts, left the FN last year to launch his own far-right political movement, Les Patriotes.

Marine Le Pen's niece, Marion, also left, weakening her aunt's support among traditional FN voters. Marion said she was withdrawing from politics completely but many believe she is biding her time to challenge her aunt for the party.

"There would be room for her if she came back," a senior FN figure told French radio recently.

Ms Le Pen has campaigned for a change of the party's name

And then there's the old conflict with Marine's father, Jean-Marie, who has launched continued attacks on his daughter and her leadership of the party he founded - most recently in a memoir about his early career, published this month.

"He managed to speak ill of me in a book which stops in 1972 - when I was four years old," Marine Le Pen told Le Figaro newspaper. "You have to be really motivated [to do that]."

Add to this the still-fresh memory of Marine Le Pen's disastrous performance in the presidential debate and the party's "identity crisis" over whether it represents economically liberal right-wingers or former communist blue-collar workers - and it is not hard to see why the FN has struggled to lead the opposition.

And that is without Laurent Wauquiez.

A new threat?

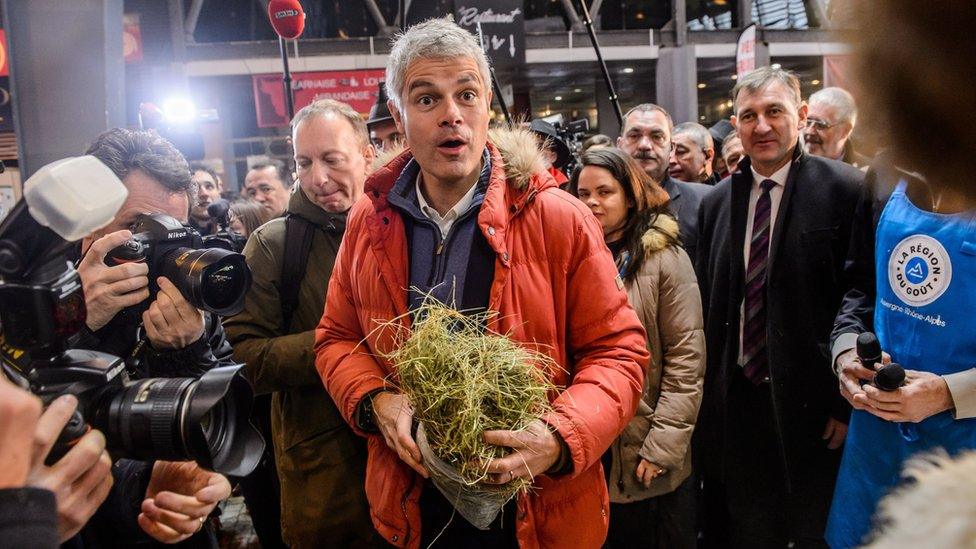

He is the new leader of France's traditional centre-right party, Les Republicains. He is young, straight-talking and unashamedly right-wing. The media have nicknamed him France's Donald Trump.

"I support the National Front," said one woman in Cogolin's weekly market, "but I think Laurent Wauquiez will emerge: he's got good ideas, he's young. Of course he's criticised but that's because the Paris upper-crust don't like him."

Laurent Wauquiez has been nicknamed France's Donald Trump

Mr Wauquiez's brash approach has won him a lot of media attention and right-wing support - and even grudging acknowledgement from MPs in President Macron's party, like Bruno Bonnell.

"Wauquiez is the same generation [as Mr Macron] and will be a strong fighter," Mr Bonnell told me. "I'm convinced he'll gather a lot of forces around his ideas. Obviously we don't share the same vision of France but he'll be a strong opposition."

But the FN's Jean-Lin Lacapelle says Mr Wauquiez is no threat to his party: "He's either poaching [our voters] and is an imposter or Wauquiez is serious and the doors are wide open for a grand alliance of nationalists. That's what Marine Le Pen is calling for."

The question of whether the FN might form an alliance with France's centre-right is hotly debated. Laurent Wauquiez has repeatedly rejected the idea and recent polls suggest that almost two-thirds of French voters are opposed to it. Among centre-right voters themselves, opposition is even higher.

Which is partly why Marine Le Pen is pushing for a change of name - hoping that it might loosen attitudes towards her party, and help open the door to alliances.

"'Front' expresses the idea of an opposition against someone or something," she told Le Figaro. "From now on, we need to go beyond that. We need to express our own ambition for government."

"I have a lot of affection for the name," said FN official Jean-Lin Lacapelle, "but it can appear a bit aggressive. It had a bad reputation in the past. Some people are happy to vote for Marine Le Pen but don't want to vote for the National Front."

The FN leader already dropped party branding from much of her presidential campaign in a bid to "detoxify" her image. But now polls suggest the French are less likely to consider the FN capable of government than before, with that perception dropping more sharply among FN voters themselves.

None of the changes of the past seven years has so far been enough to secure the party pride of place in either government or opposition.

Marine Le Pen says she even propelled the recent change in French politics, opening up a new division between globalists and nationalists. But, she said, it was "Emmanuel Macron [who] passed through the door that we opened".

- Published8 May 2017

- Published7 May 2017

- Published10 February 2017

- Published16 May 2014

- Published9 January 2024