Spy poisoning: What the diplomat expulsions mean for Russia

- Published

The war of words between the UK and Russia

This is building into the most serious diplomatic crisis between Russia and the West since Moscow's seizure of the Crimea.

Whatever the denials, Britain's allies have clearly accepted London's view - that the use of a military grade nerve agent in an assassination attempt in a British city was "highly likely" to be the work of the Russian state.

The collective expulsion of Russian diplomats from the US and 14 European Union states is a remarkable show of solidarity with Britain; even more so because it comes at a time when UK-EU relations are strained due to the Brexit negotiations.

Indeed Donald Tusk, President of the European Council, noted that "additional measures, including further expulsions were not excluded in the coming days" - a tough signal to Moscow as it considers how it will respond.

This is a significant diplomatic victory for Prime Minister Theresa May, and also marks a significant toughening of the Trump administration's stance towards Russia.

Britain was swift to point the finger at Moscow. But then it largely avoided public diatribes, seeking out every available international forum, from the EU, to Nato, the UN, and the highly relevant OPCW (Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical weapons) to set out its evidence and justify its conclusions.

This patient diplomacy has now paid off.

The BBC's Paul Adams looks at why the UK is expelling 23 Russian diplomats

One must assume that many or most of the Russian diplomats designated for expulsion are intelligence operatives. Thus the cumulative impact on Russia's overseas intelligence activities could be considerable.

Russia must now ponder what actions it will take in response. But President Putin could never have imagined there would be this degree of solidarity.

Russia perceived Britain as weak and increasingly isolated; the EU as distracted; and the Trump administration as off-balance and compromised by President Trump's own curious unwillingness to castigate Moscow.

Mr Putin may have made a serious mistake. This is in many ways a remarkable display of concerted European action, though he may prefer to note that by no means all members of the EU have participated.

It may be the US shift, though, that is most significant. Mr Trump's approach to Russia has been curiously lenient and unfocused. But the US diplomatic action is noteworthy because it doesn't just involve throwing out 48 diplomats in the US and closing the Russian Consulate General in Seattle.

It also includes the separate expulsion of 12 Russian diplomats at the UN who are described by the State Department as "intelligence operatives" who have "abused their privilege of residence in the United States".

Only a few days ago Mr Trump was seemingly setting aside the Salisbury attack and talking about a new summit with Mr Putin. Will this now go ahead? And if so when?

It remains to be seen what the frostiness will mean for long-term US-Russia relations

The current row comes just as the cast-list overseeing US foreign policy is changing significantly, with former CIA chief Mike Pompeo taking over at the State Department and John Bolton at the National Security Council.

While both men are closely in tune with the president on policy towards Iran and North Korea, Mr Pompeo must have a comprehensive understanding of Moscow's disruptive activities from his intelligence job, and Mr Bolton has long been an advocate of a tougher stance towards Moscow.

Russia is clearly in the diplomatic dog-house; and a frostier period of relations between Moscow and the West beckons. But this is also a moment for Western governments to define exactly what the Russian "problem" is.

Rhetoric about a new "Cold War" and a significant defensive build-up is all very well, but probably wide of the mark.

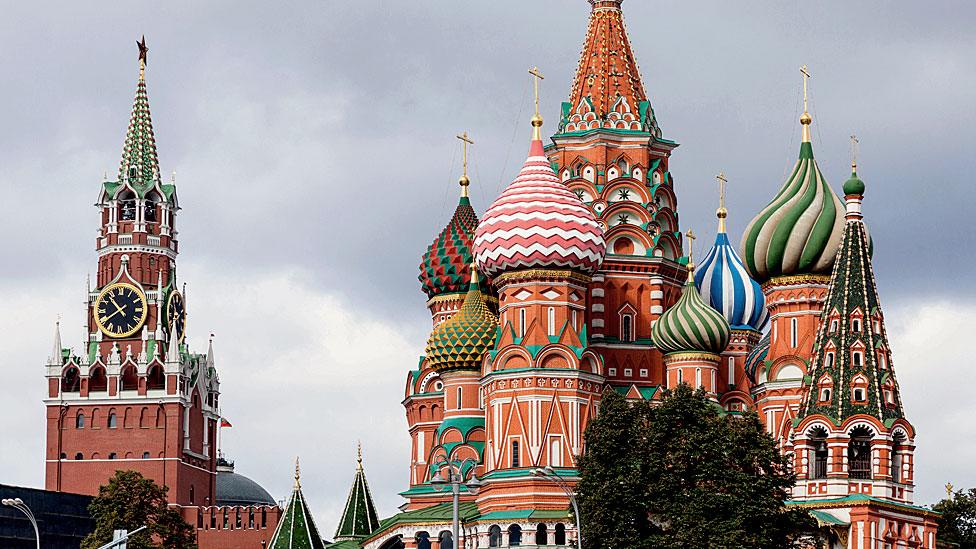

The poisoning of Sergei Skripal - which the UK and its allies blame on Moscow - has put Russia in the diplomatic dog-house

It overstates the case: Russia is not the Soviet Union, a global player with an ideology that mobilises people around the world. It has its strengths but also its weaknesses, not least its economy.

In recent years Mr Putin has made a good hand out of focusing Russia's capabilities on places that matter to Russia, where it has strong historical or diplomatic links.

Essentially Russia is a power close to home, in what Russians call the "near abroad". Thus it can mount a threat to Georgia or Ukraine. Syria in a strange way could also be included in this "near abroad".

Russian "power" may be reaching its zenith. It retains, though, an extraordinary ability to create trouble more broadly through hacking, information warfare, and by backing extremist political parties.

To counter this, Western governments and societies may need to spend some more on defence; but they certainly need to spend a great deal more on making their societies more resilient.

The first thing is to reach a common and comprehensive assessment of the problem. And the use of a nerve agent in the quiet cathedral city of Salisbury may just have set that process in motion.

- Published8 October 2018

- Published17 March 2018

- Published2 September 2020

- Published26 March 2018

- Published20 March 2018

- Published25 March 2024

- Published7 March 2018

- Published6 March 2018