Crossing Divides: Europe 'more split' than decade ago

- Published

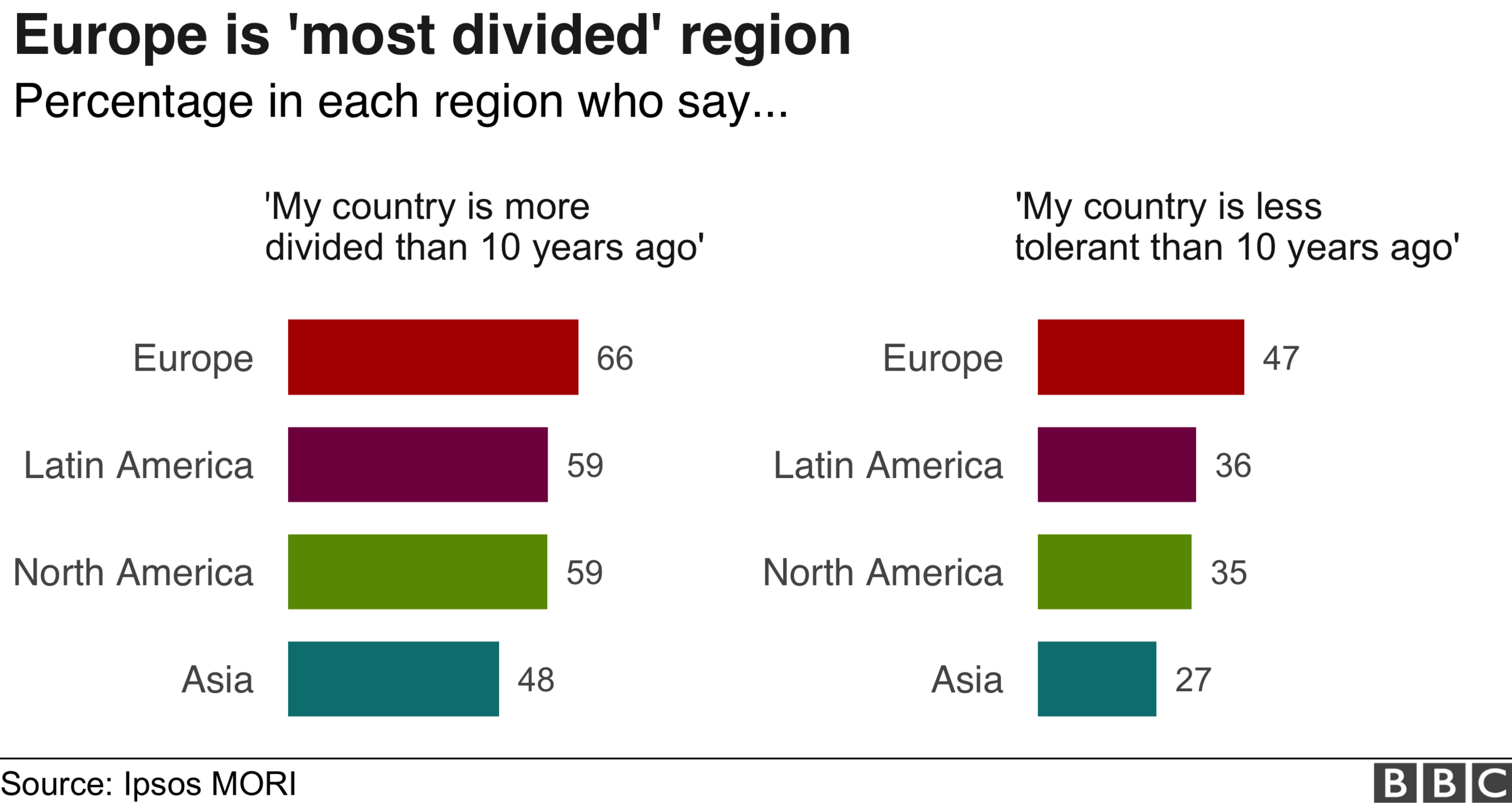

Most Europeans believe their countries are more polarised than 10 years ago, and 47% see their societies as less tolerant, a poll for the BBC suggests.

In the online Ipsos Mori poll, external spanning 27 countries, 66% of people in Europe felt their nations were "more divided", the highest proportion worldwide.

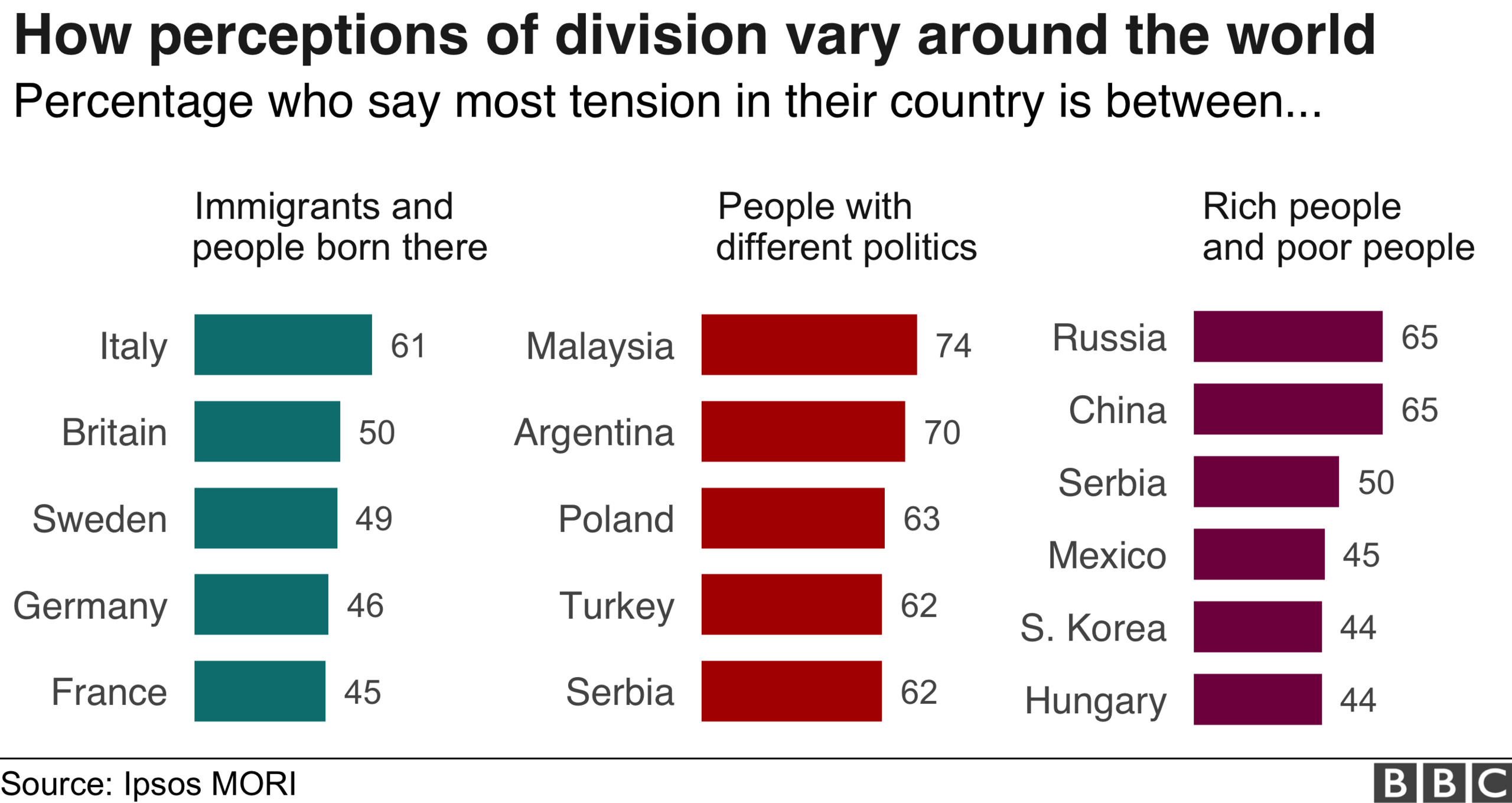

Politics emerged as the main cause of tension globally, being identified by some 44% of all 19,428 respondents.

Half of Britons cited a divide between immigrants and nationals.

It was the source of social division most commonly identified in the UK, followed by differences of religion (47%), ethnicity (41%) and political views (40%).

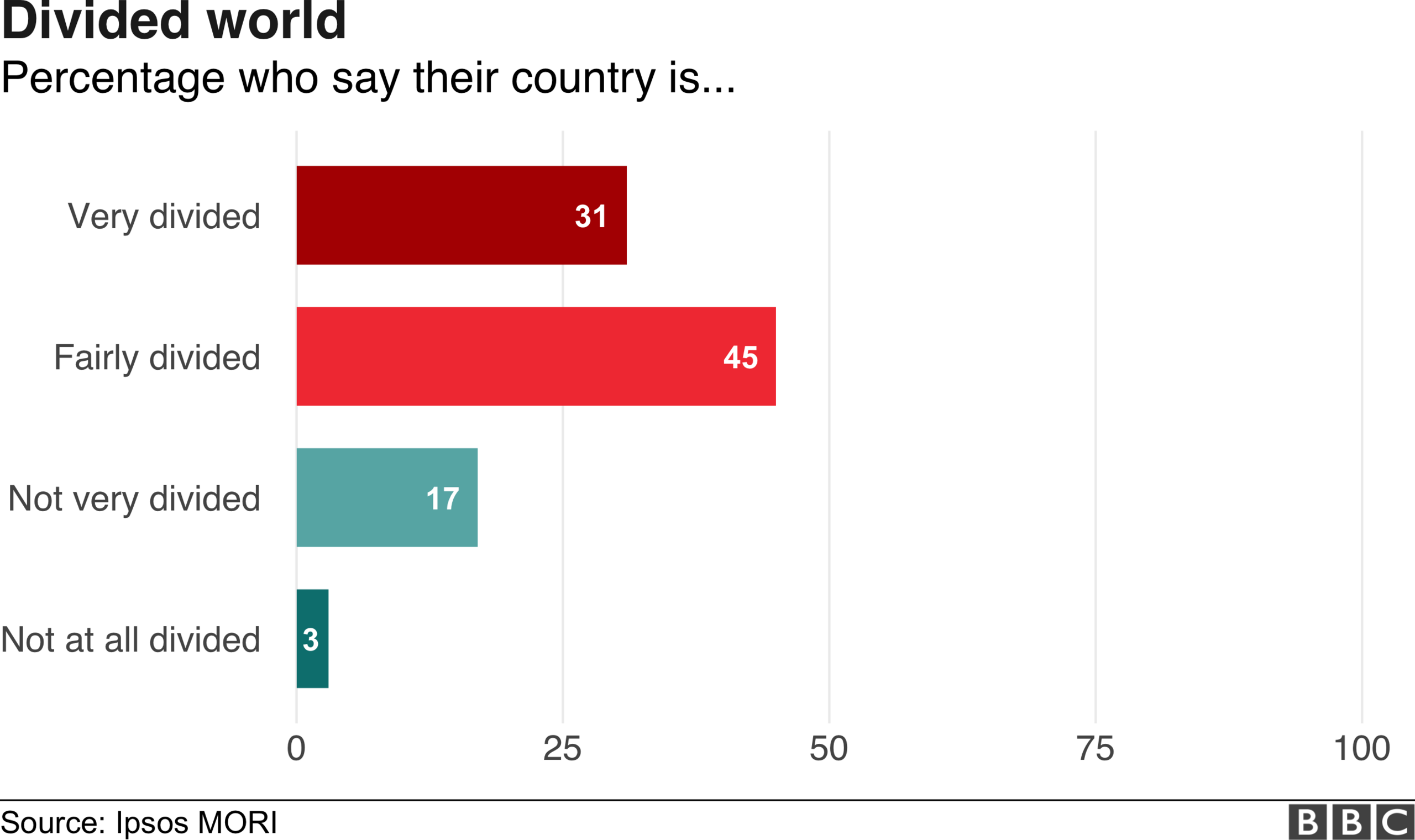

The worldwide results showed that three-quarters of respondents agreed that their society was divided, with one-third of those saying it was "very divided".

Fractures were also perceived to be growing deeper, with a clear majority saying their country was more polarized than 10 years ago. Only 16% of respondents believed divisions were less acute today.

The European picture

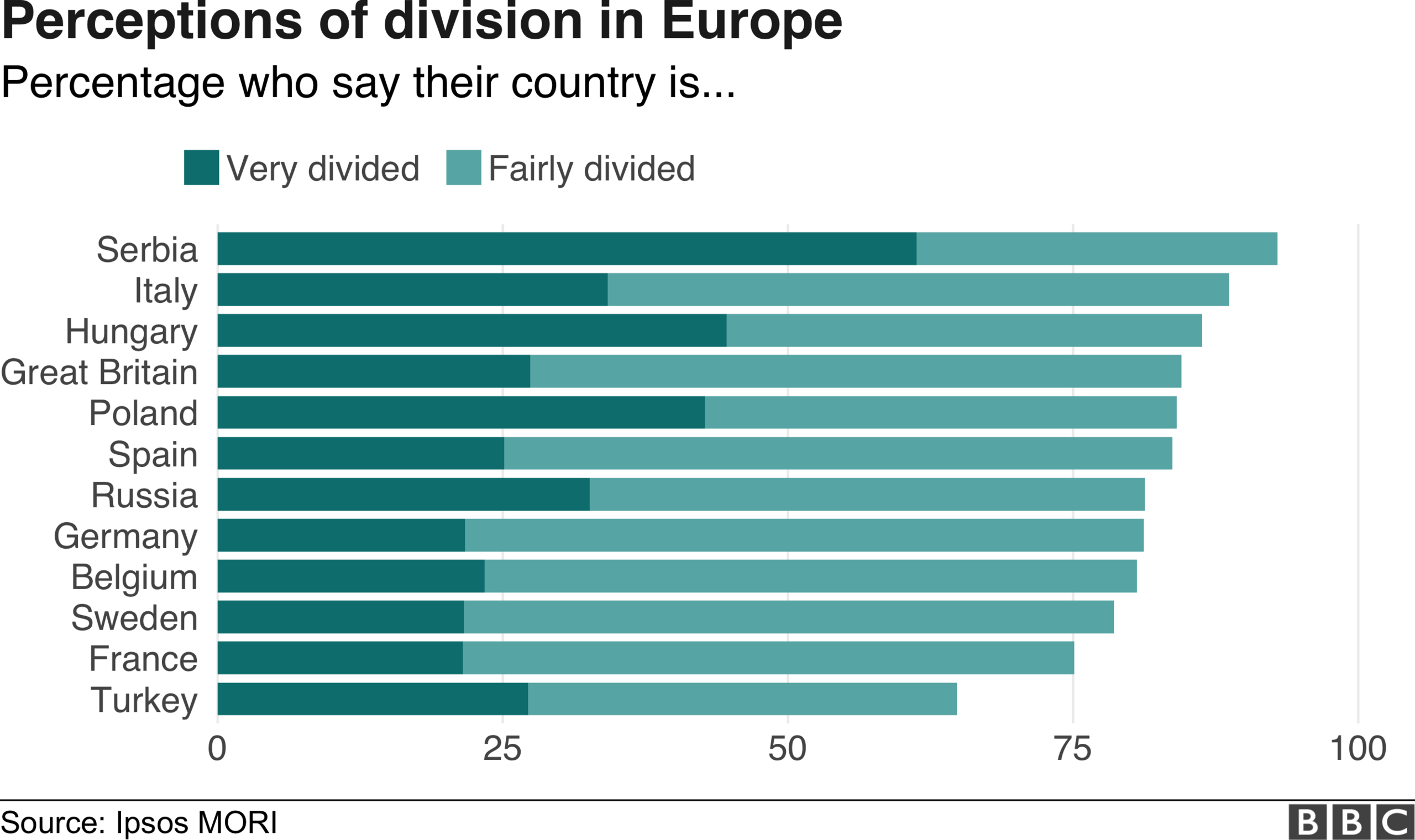

The poll collected information from 11 European countries: Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Serbia and the United Kingdom.

Serbia was where perceptions of differences were strongest, with 93% of respondents saying their society was either very or fairly divided.

"All Europe shows a similar trend, with at least three out of four respondents saying that their respective society is very or fairly divided," said Ipsos Mori's Glenn Gottfried, who oversaw the fieldwork.

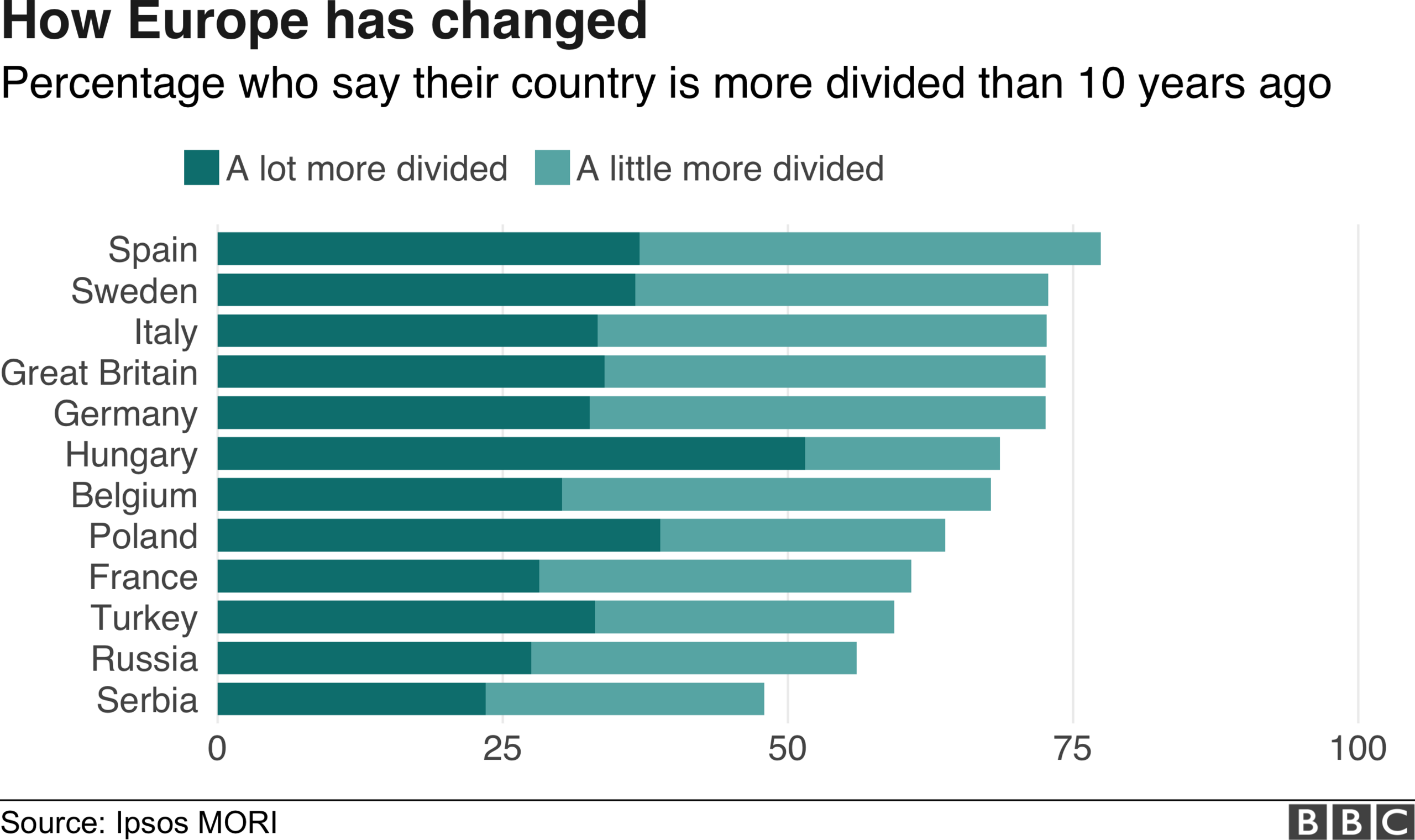

Mr Gottfried said Europeans appeared to believe divisions had grown more pronounced.

"This could be a reflection of the political climate and a swing towards the right that we have seen in parts of the continent, or at least the political climate could be a result of people feeling more tensions. The two are correlated," he said.

As in Britain, respondents in Germany and France most often identified a division between immigrants and nationals.

Yet more traditional perceptions of social divisions persist, Mr Gottfried added.

"Tensions based on class and income still exist. In Britain, for example, about a third see tension between rich and poor, and in Hungary more people see tension between rich and poor than in relation to immigrants."

The Hej Framling! (Hey Stranger!) group puts migrants and locals in touch so they can go running together

Serbia's haves and have-nots

Dejan Anastasijevic, BBC Serbian Service

About 80% of the population are Christian Orthodox Serbs, so there are no grounds for stark ethnic or religious divisions.

But Serbia holds a record income-inequality among European countries, according to last year's GINI index measure of inequality.

A quarter of the population lives below the poverty line, while the wealthiest 20% earn 10 times more than the poorest fifth. In the EU, this ratio is five-to-one. The gap between the haves and have-nots has widened over the last five years.

Politically, there are sharp divisions over Kosovo, which broke off from Serbia in 2008. Accepting the territory's independence (without formally recognizing it) is a precondition for Serbia's accession to EU.

But while most Serbs want EU membership, they also want Kosovo back. So the debate is always heated.

Latin American rivalries

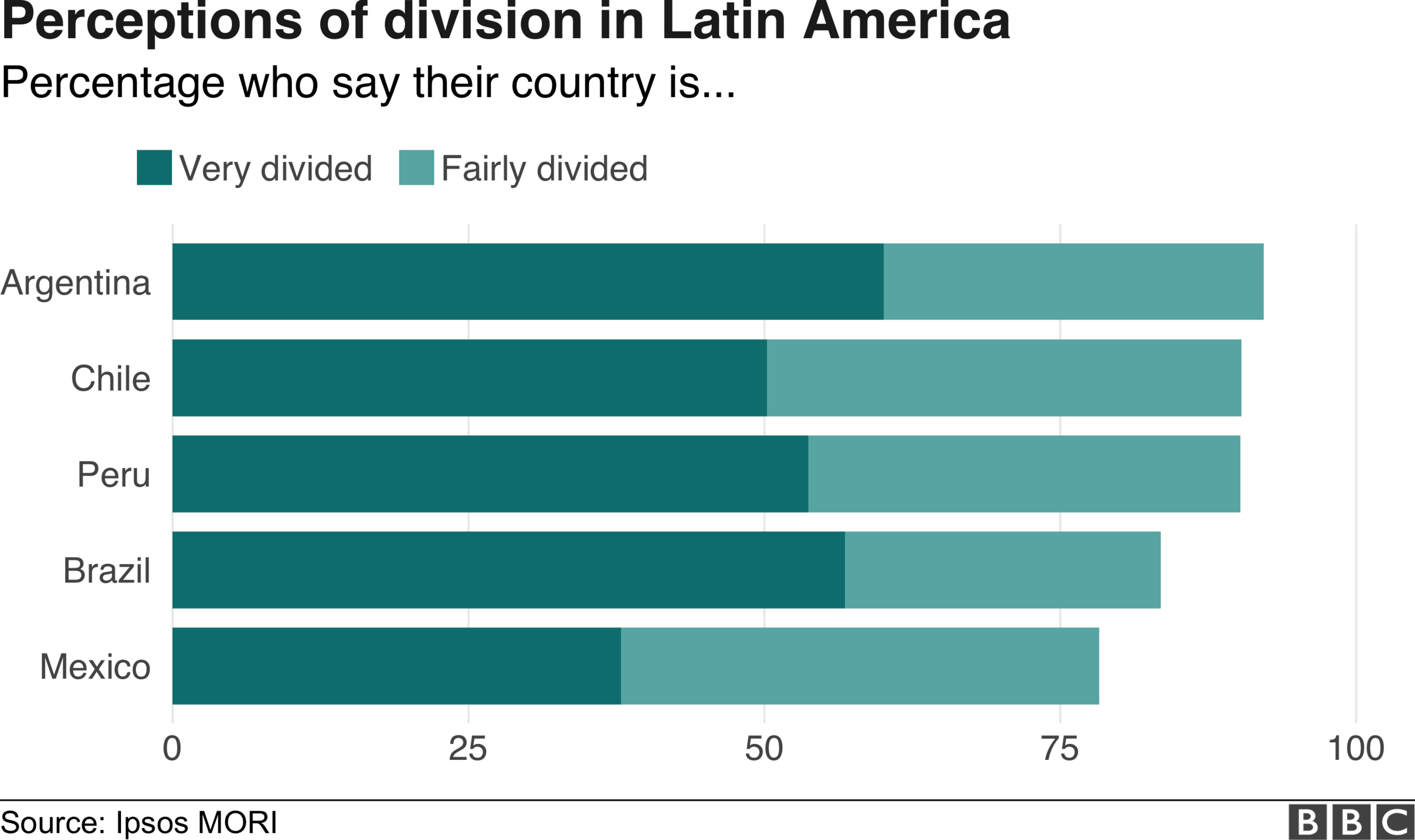

Within the Latin American countries surveyed - Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Chile and Peru - at least three-quarters of respondents perceived big divisions, most often in politics but also between the rich and poor.

Perceptions of tension are highest in Argentina, with 92% of respondents saying their country is "very" or "fairly" divided - and almost 40% suggesting it has worsened over 10 years.

Some 70% of Argentines cited division over political views.

"That's very, very high," said Mr Gottfried. "With the exception of Malaysia, in this poll Argentina comes on top in terms of seeing political differences as the most prevalent issue."

The survey suggests Latin America's political divisions were even more pronounced than Europe's, having been identified by more than half of respondents as a cause of polarization.

However, while 68% of Europeans felt the divisions had widened over the last decade, that figure for Latin America was considerably lower, of 59% of respondents in the countries polled.

Argentina's political rift

President Mauricio Macri campaigned for office in 2015 with a promise to do away with "la grieta" - the term meaning "the rift" that described the deep state of polarization that had grown under previous left-wing Kirchner administrations (2003-15).

Yet the rift, which is part of the everyday rhetoric of Argentines and is recurrently mentioned by the media, is far from being closed under Macri's Conservative administration - if anything, it may have deepened, given that almost 40% of people suggested their country was more divided than a decade ago in the Ipsos Mori poll .

"It is interesting how people perceive 'the rift' to be a recent phenomenon", says sociologist Martin Gendler, from the University of Buenos Aires.

"In fact this country was founded on a number of dualities and rivalries that have been there since the early days of the nation, even more acutely than in other nation states. [They] have been reinterpreted and re-signified throughout the years, but they have always largely revolved around the confrontation of populism versus anti-populism."

A largely tolerant world?

The survey also reveals some positive trends, said Mr Gottfried.

Two-thirds of respondents agreed that people across the world have more in common than they have differences.

"Only a small number of people think that mixing with people from different backgrounds, cultures or points of view causes conflict," said Mr Gottfried.

A third said those interactions can sometimes lead to misunderstandings but these can usually be overcome, while 40% believe they may actually lead to better mutual understanding and respect.

Some 74% of Canadians said their society was very or fairly tolerant of people with different backgrounds or points of view, followed by 65% of Chinese and 64% of Malaysians.

'Harmonious' China?

Yuwen Wu, BBC Chinese Service

While political, religious or gender divides might manifest themselves in fierce debates or protests in other countries, there is very little tolerance of dissent in China.

Heavy state control of media prevents meaningful and open political discussion. As a result, social divisions are often papered over. Only 7% of respondents to the Ipsos Mori poll believed their society was "very divided".

Former president Hu Jintao advocated building a "harmonious society", a fair and just society where rule of law was observed and people trusted each other. The slogan has been seen and heard everywhere. But when citizens find their postings removed from social media because they are deemed offensive by censors, they say "my post has been harmonised".

Even so, the leadership recognises the income divide reflected in China's GINI coefficient indicating a high level of income inequality. President Xi Jinxping's "China Dream" to rejuvenate the nation has undoubtedly inspired many Chinese people - but it has certainly not worked out for everyone.

Data journalism by William Dahlgreen, BBC Visual Journalism.

Crossing Divides

Crossing Divides: a week of stories about people creating connections in a polarised world.

How to survive a difficult conversation

- Published23 April 2018