The secret world of Russia's North Korean workers

- Published

A waitress at Koryo, a North Korean restaurant in Moscow

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un is preparing for his first-ever summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Russia is currently home to thousands of North Korean migrant workers whose future remains in the balance - UN sanctions passed in 2017 require them to leave by the end of this year.

Both the workers and the companies that employ them are watching to see if progress on the diplomatic front might open a way for them to stay.

Tucked away in the courtyard of a discount shopping mall not far from the city centre is one of Moscow's more unlikely tourist attractions - Koryo, a North Korean restaurant.

Owned and staffed entirely by North Koreans it offers adventurous diners a little taste of Pyongyang.

There's North Korean music playing on TV, and kimchi and cold noodles on the menu.

On the eve of Kim Jong-un's meeting with Vladimir Putin in Vladivostok the place is heaving.

Many of the tables are pushed together to accommodate big groups.

"Is today a North Korean holiday?" I ask the waitress. "No," she says in faltering Russian. "It's just an ordinary day."

The staff at Koryo are just some of the 8,000 or so North Korean migrants employed by businesses across Russia.

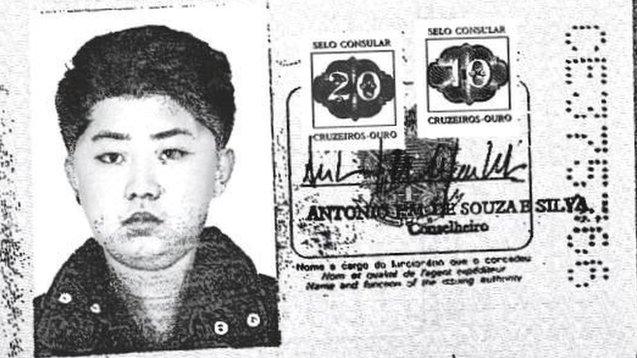

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un is in Russia but the two countries already have a long relationship

This latest figure was confirmed recently by Russia's Foreign Ministry and it marks a significant drop on the up to 40,000 who were working in the country until two years ago.

The majority have been forced to leave in order for Russia to comply with UN international sanctions prohibiting the employment of North Koreans because of the North's nuclear programme.

Since the UN sanctions resolution - which came into effect in September 2017 in response to a North Korean missile test - the only North Koreans who have been able to come to Russia to work are those whose employment contracts were signed before that date, the Ministry of Labour press office told BBC Russian.

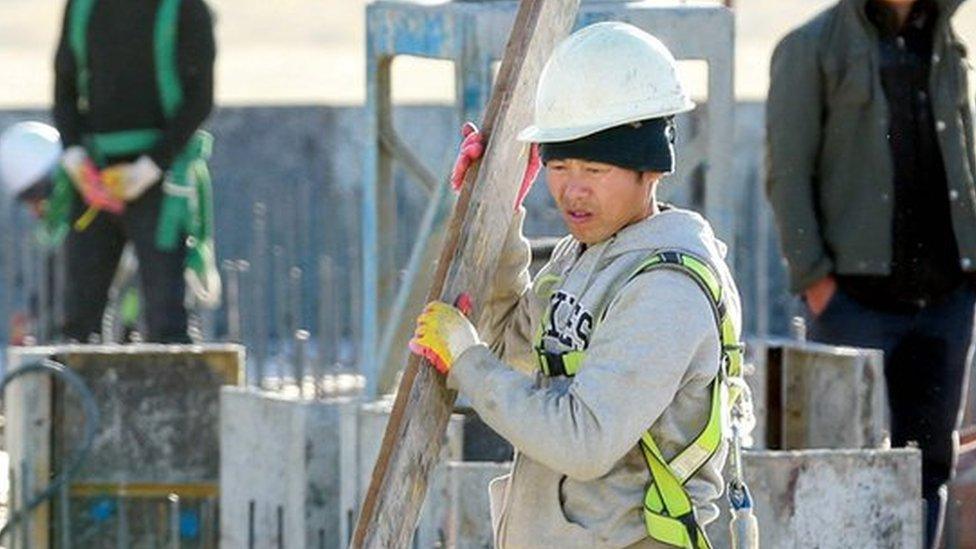

According to Ministry of Labour statistics, more than 85% of North Korean migrants work in construction.

The rest are involved in a range of jobs from garment work and agriculture, to logging, catering and traditional medicine.

For poverty-stricken North Koreans landing a job in Russia is a dream ticket, said Professor Andrey Lankov, a North Korea expert at Seoul's Kookmin University.

"It's impossible to find a job in Russia without paying a bribe [in North Korea]."

Tens of thousands of North Korean labourers work in Russia and human rights groups say it is a form of slave labour, reports Stephen Sackur

That's despite the sub-standard accommodation and conditions often akin to slave labour which have been endured by many migrants.

In a well-documented case in 2015, immigration officials in Nakhodka in Russia's Far East found three highly-qualified North Korean agronomists clearing snow on the roads.

Their employers - a Russian-North Korean company - claimed it was a one-off departure from their main job monitoring the harvest, but the authorities were unconvinced. All three were deported.

According to Russia's labour ministry, North Koreans are paid on average $415 a month, 40% less than the average salary in Russia.

"You have to hand over half your pay to the [North Korean] state," Prof Lankov told BBC Russian.

"But what's left is still far more than you could earn at home."

Life in North Korea

Russian companies wishing to employ North Koreans must apply to the Ministry of Labour for a "quota" and permission to employ a foreign worker costing the equivalent of about $200 per person.

Many are in the Russian Far East where Kim Jong-un and Vladimir Putin are meeting this week.

With local populations shrinking, it's a region with a labour shortage, but despite this sanctions have had an impact on the numbers of North Korean workers. Last year a quota of 900 was issued, a big drop on previous years.

Labour ministry figures for 2018 showed North Koreans were working all over the country, with 40% of all licences issued to businesses in Moscow and St Petersburg regions.

In St Petersburg it was widely reported that North Korean construction workers were involved in building a football stadium for last year's World Cup.

Another St Petersburg company, the BTC Group which makes uniforms for the Russian army, had a licence to employ 270 North Koreans in 2017 - although a spokesman denied any had actually been offered jobs. In 2018, BTC applied for licences to employ Vietnamese workers instead, according to labour ministry data.

North Koreans have been found working abroad in conditions likened to slavery

In Karachay-Cherkassia in the North Caucasus, the Yuzhniy agricultural company in 2018 had licences for 150 North Koreans on its books growing vegetables for its supermarket supply business.

And in Sverdlovsk in the Ural region, there were even six North Korean trainers working at a factory table-tennis club in 2017.

The largest employers of North Koreans in Russia are North Korean-owned companies.

Data from Russia's Spark business information system suggests there were about 300 registered to operate by the beginning of 2018.

More than half are involved in construction, like the Enisei company in Krasnoyarsk, in Siberia, which recently built a new prison.

The national airline, Air Koryo, is registered to operate flights from Vladivostok, and there's also branch of the North Korean Foreign Trade Bank. Neither responded to BBC calls this week.

Some 8,000 North Koreans are employed in businesses across Russia

The majority of North Korean companies in Russia are owned by private individuals.

It's a sign, says Andrey Lankov, of how decentralised North Korean business has become.

"The Foreign Trade Ministry is at best a first among equals, but ministries, departments, parties, small organisations and entrepreneurs can also start businesses abroad.

"The owner of a private company could be a government official, someone from the security services, or just a North Korean entrepreneur with money and good contacts."

The UN sanctions have been very unwelcome news for many businesses in Russia.

In Vladivostok, on the Pacific Coast, the Yav-Stroi construction company used to be one of the biggest employers of North Korean migrants, with licences for 400 in 2017.

North Koreans staff a route from Vladivostok

"We can't manage without migrants," a company spokesman, who asked to remain anonymous, told the BBC soon after sanctions were introduced.

In Moscow the Eastern Medicine Clinic used to employ 10 North Korean doctors. In 2018 the quota was reduced to just four.

"If they have to leave our patients, many of whom are disabled children, will lose their treatment," then director Natalya Zhukova told the BBC when sanctions were introduced.

The UN sanctions also prohibit joint ventures, but there have been some exceptions.

Rasonkontrans was given special exemption in the UN resolution - it's a high-profile Russian-North Korean company involved in a major rail and port project in the Russian Far East.

It's clear Russian officials would like to find ways to ease the sanctions against North Korea.

This stadium in Saint Petersburg is said to have been built with the help of North Korea labour

At a rare summit with his North Korean counterpart in Moscow in April 2018, Russia's Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said the two sides had discussed ways to boost economic ties while complying with the UNSC resolution.

"The possibilities to do so exist," he said.

This month a delegation from Russia's parliament visited North Korea with very much the same aim in mind.

"We are neighbours, we are bound by friendship and great victory, and we must help each other," MP Kazbek Taysaev told the BBC after the visit.

"Especially because of the sanctions imposed on North Korea for the past 70 years, and the sanctions under which our country now finds itself. We are soul mates."

Back at the Koryo restaurant in Moscow the staff are reluctant to talk to the BBC about what the future will hold.

But diners looking for a taste of North Korea might be advised to take the chance while they still can.

Additional reporting by BBC Russian's Petr Kozlov and Anastasia Golubeva

- Published1 March 2018

- Published3 February 2018

- Published29 December 2017