Basque group Eta apology criticised by victims

- Published

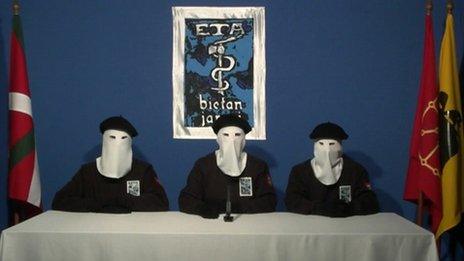

The Basque armed organisation Eta is expected to announce its dissolution next month

An apology from the Basque organisation Eta to those killed in its armed independence struggle has been rejected by victims' groups.

The separatists in the Spanish Basque Country asked for "forgiveness" for killing people without "a direct participation in the conflict".

Victims' groups accused Eta of seeking to justify its use of violence and attempting to rewrite history.

Eta is widely expected to announce its dissolution in the coming weeks.

The militants killed more than 800 people and wounded thousands more over 40 years of conflict as they sought to establish an independent Basque state in the area spreading across northern Spain and into south-western France.

"We want to show respect for the dead, those injured and the victims that were caused by the actions of Eta... We truly apologise," it added, admitting its "direct responsibility" in the "disproportionate suffering" in the Basque country.

The Victims of Terrorism Association (AVT) said the statement was another step in Eta's strategy of "diluting its true responsibility" and manipulating history "to whitewash the criminal past".

AVT leader Maria del Mar Blanco told AFP news agency: "I find it shameful and immoral that they should make a distinction between people who deserved a bullet in the back of the head or a bomb in their car and accidental victims who did not deserve it."

Another group, the Collective of Victims of Terrorism (COVITE), also criticised that distinction, and said Eta was maintaining its story of a "non-existent conflict" and aiming to "blur its responsibility over crimes committed".

Spain's government said Eta was defeated politically and operationally and had not achieved any of its goals.

Eta also said it was committed to moving forward with the process of reconciliation in the Basque country.

In September 2010, the group announced that it would not carry out further attacks, and it declared a permanent ceasefire in January 2011.

In April 2017 the militant group revealed the locations of its weapons caches and said it had completely disarmed.

Eta carried out many attacks including the one which killed Spanish Prime Minister Luis Carrero Blanco in 1973

Eta first emerged in the 1960s as a student resistance movement bitterly opposed to Gen Francisco Franco's repressive military dictatorship.

Under Franco the Basque language was banned, the region's distinctive culture was suppressed and intellectuals were imprisoned and tortured for their political and cultural beliefs.

Franco's death in 1975 and the transition to democracy brought the region of two million people home rule.

Many of those who were killed were members of Spain's national police force, the Guardia Civil, and both local and national politicians who opposed to Eta's separatist demands.

- Published21 August 2023

- Published8 April 2017

- Published16 May 2019

- Published20 October 2011

- Published5 September 2010

- Published5 September 2010