Irish abortion referendum: The people travelling #HomeToVote

- Published

Meet the women who travelled #HomeToVote on Friday

Irish voters from around the world returned to cast their ballots in Friday's referendum on whether or not to repeal the country's Eighth Amendment. That clause in the Irish constitution in effect outlaws abortion by giving equal rights to the unborn.

The #HomeToVote hashtag has trended on Twitter for most of the weekend, as men and women shared their journeys home.

From car shares, to offers of beds for the night, the movement was propelled by social media. A similar movement also took off ahead of the 2015 vote that legalised same-sex marriage.

People on both sides of the argument travelled back to vote, but the movement was spearheaded by the London-Irish Abortion Rights Campaign - a pro-choice group that tried to mobilise an estimated 40,000 eligible emigrants.

The Eighth Amendment came into being after a 1983 referendum, so no-one under the age of 54 has voted on this before. For many, the vote was touted as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to have their say on women's reproductive rights.

A warm welcome for people travelling #HometoVote in Dublin

Thousands of Irish women travel every year for abortion procedures in Britain. For women who made the reverse trip to vote Yes to repeal the Eighth, the journey held a lot of symbolism.

"I think of it every time I've travelled to and from the UK; it's always on my mind," 21-year-old student Bláithín Carroll said before boarding her plane back.

Bláithín Carroll says the vote is a chance for Ireland to "really progress" as a modern country

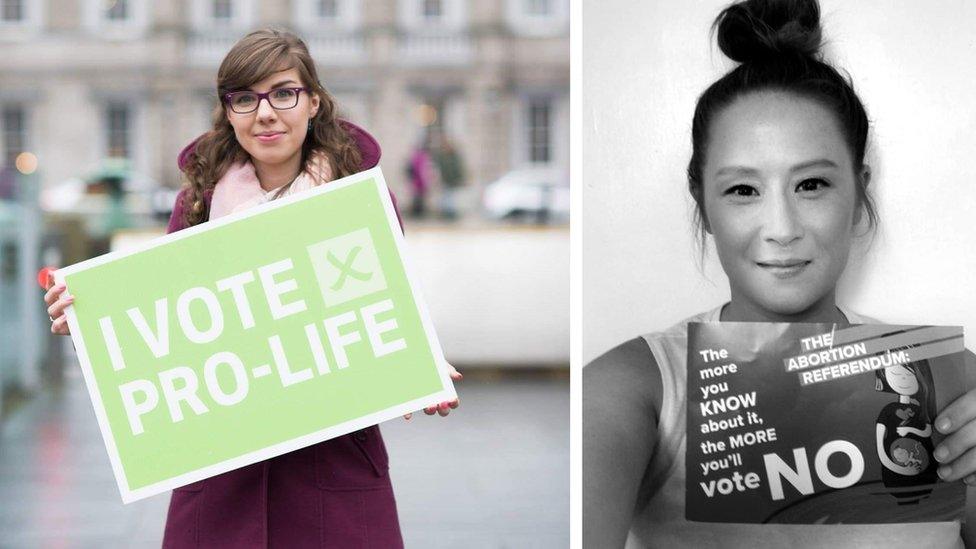

Karen Fahy, 26, and Maria Mcentee, 24. travelled back from London to vote against the change.

They argue that young women opposed to abortion have been stigmatised for their views in the run-up to the referendum and believe many others like them have kept their opinions quiet.

"A lot of people don't want to get involved in the polarising debates online," Maria said. "But you can kind of infer who is voting no, because they'll be the people who don't have repeal stickers on their picture or post things about repeal."

The 24-year-old said she had always been "a bit indifferent" to the abortion issue until she saw a campaign video showing a procedure.

Karen Fahy (left) and Maria Mcentee (right) are a part of London-Irish United for Life

Currently living in the UK where abortion is legal (except in Northern Ireland), Karen said she had concerns about the proposal presenting abortion as "the first and only choice" for women with unplanned pregnancies.

"I don't want to see that coming to Ireland, and I think we can do a lot better," she said. "We should be investing and providing support for women in crisis pregnancies."

"In those very difficult situations when there's a very severe disability, we should provide more child benefit and support women in education."

Abortion is only currently allowed in Ireland when the woman's life is at risk, and not in cases of rape, incest or foetal-fatal abnormality (FFA).

Round trip from Japan

Clara Kumagi, a keen repealer, has taken time off work in Tokyo to travel back thousands of miles to cast her vote. She was already on her way back there by Friday afternoon.

"I want to live in a country where I feel safe, where I know that I have the autonomy to make decisions about my own body," the 29-year-old said.

Clara says she always knew she wanted to return #HomeToVote to repeal, after being ineligible for the 2015 equal marriage ballot

"For me, the act of travelling was something that I felt was important to do. How many kilometres do Irish women travel every year? For me 10,000km felt like the least I could do."

Her student brother also travelled travelling back from Stockholm to vote. Irish men living as far away as Buenos Aires and Africa have posted online about their journeys home. Pro-repeal men have shared their support for the movement using the #MenForYes hashtag.

Mother-of-three Amy Fitzgerald, 38, took three flights to return to Ireland from Prince Edward Island in Canada.

Amy's flights were a birthday present bought by husband Padraig, whom she describes as her "favourite feminist"

"There's always people who will need an abortion," she said, reacting to accusations that the proposed new law could lead to abortion "on demand" as a back-up to contraception.

The government's proposed abortion bill would allow unrestricted terminations up to 12 weeks, with allowances made afterward on health grounds.

"No-one wants one until you actually need one. No little girl dreams of having one," Amy said.

Irish actress Lauryn Canny, 19, who travelled back from LA to vote, said that that concern over abortion access loomed over her teenage years.

She recalls being "constantly terrified" of the risks of having sex while growing up.

"I remember one of my friends said: Well if I got pregnant, I would just commit suicide. I couldn't tell my Mam," she says.

Lauryn (second left) pictured with her sisters and mother, said every vote would count

"I have two baby sisters now, and they're six and seven, and I just really hope that when they are growing up they feel safer and feel like they're growing up in a more compassionate Ireland that will care for them if they're in crisis."

Lauryn was able to afford flights after her grandmother organised a "whip-round" to raise money.

Student Sarah Gillespie, 21, travelled back from the US to vote - but for the other side.

She felt so strongly about the issue that she cut short her time studying abroad in Pennsylvania to return to Ireland to canvas for a No vote.

Physics student Sarah rearranged her flights home to canvas against the repeal

She describes herself as a feminist, but believes the rights of the unborn should be considered too.

Having previously voted for marriage equality, she wants people to recognise that the issues are different, and that No voters were not simply voting according to strict religious beliefs.

"I would never judge or get angry at a woman who went abroad, I just wish there was better support here," Sarah said.

She hoped that, whatever the result, people respected the outcome.

Unlike in other countries, most eligible voters outside Ireland had to physically travel back to cast their ballot.

Only those who have lived away for less than 18 months were legally entitled to take part in the referendum.

Because of that rule, Oxford University lecturer Jennifer Cassidy was ineligible to vote - but campaigned for repeal. Those ineligible used the #BeMyYes hashtag to encourage support for Yes.

The 31-year-old helped support the motion, alongside a number of Irish students

"I understand it to an extent - Ireland has a huge global community and policing that would be difficult," she said.

"But it seems illogical and counter-intuitive to the Irish narrative, which is one of emigrating for a while and then coming home."

Oxford University was one of several UK institutions whose student unions offered to help subsidise travel.

Under the current system, people are not routinely removed from Ireland's electoral register, so polling cards were being sent to the family homes of emigrants who were no longer eligible.

It was feared that if the result was close, people may have complained about the #HomeToVote movement and whether everyone was actually legal to vote.

- Published26 May 2018

- Published21 May 2018

- Published18 May 2018

- Published20 May 2018

- Published21 May 2018