Doctor on trial over Spain 'stolen babies' scandal

- Published

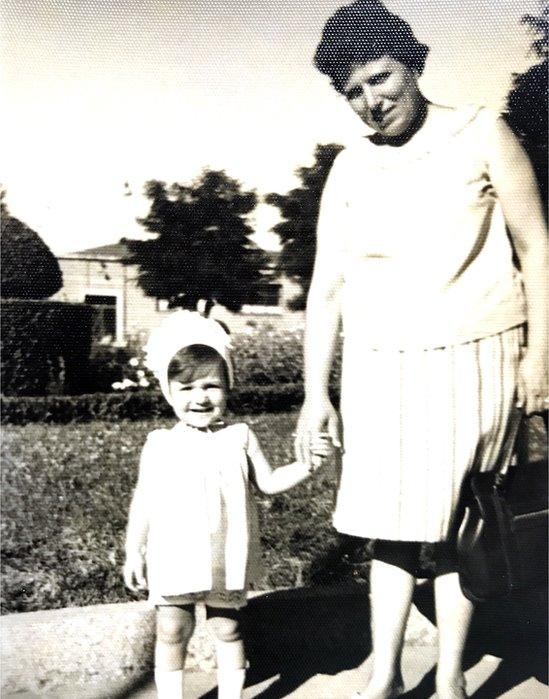

Manoli Pagador told the BBC in 2011 how her baby son was taken away from her in 1971

When an 85-year-old gynaecologist goes on trial in Madrid on 26 June accused of abducting a baby, thousands of victims of a sinister, sprawling network of illegal adoptions will be looking for answers.

They will also be hoping that the case triggers wider investigations into the scandal.

Dr Eduardo Vela will become the first person to stand trial for what victims' groups claim was a secret practice that saw hundreds of thousands of babies stolen and sold under the dictatorship of Gen Francisco Franco and after his death in 1975.

In the years immediately after Spain's 1936-1939 civil war, children were removed from families identified by the victorious fascist regime as Republicans and given to families considered more deserving.

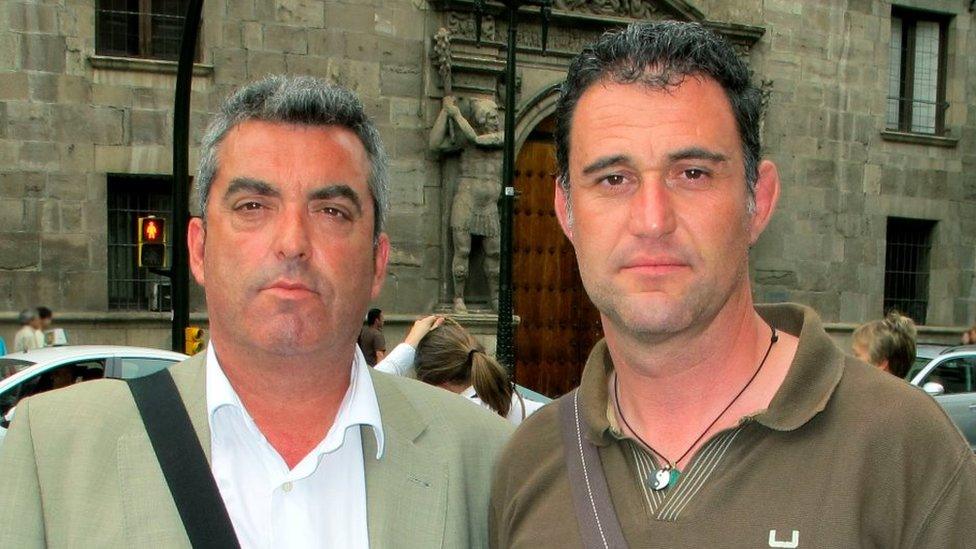

Little was known about the private trafficking of babies that continued in the 1960s until two men went public with their story in 2011.

Antonio Barroso and Juan Luis Moreno revealed they had been bought by their respective fathers from a priest in Zaragoza.

Antonio Barroso (L) and Juan Luis Moreno uncovered the scandal after realising they had been stolen as babies

Mr Barroso, who founded the association Anadir (National Association for Irregular Adoption Victims) calculates that 15% of adoptions in Spain between 1965 and 1990 were the result of babies being taken without consent from their biological parents.

That would amount to some 300,000 people.

What Eduardo Vela is accused of

Inés Madrigal, the baby Dr Vela is accused of abducting in 1969, believes her birth mother may have been deceived or bullied into giving her away.

"They told my mother that the biological mother was a married woman who couldn't keep me. She had had an affair while her husband was away," she says.

Dr Vela has admitted signing the birth certificate stating that Inés Madrigal's adoptive parents, Inés Pérez and Pablo Madrigal, were her biological mother and father.

He told the investigating judge that, in his capacity as director at the now-defunct San Ramón clinic in Madrid, he signed papers without reading them.

Inés Pérez (R) said she had been given the younger Inés as a gift by Eduardo Vela

DNA testing has shown that Ms Madrigal is not related to her late parents.

Before her death in 2016, Inés Pérez told the judge that Dr Vela had given her the baby as "a gift" after a Jesuit priest had introduced her to the gynaecologist as a favour, because she and her husband could not have children.

Dr Vela and his defence lawyer declined to comment.

A slowly unfolding Spanish scandal

In 2008 investigating judge Baltasar Garzón estimated that 30,000 children had been stolen from families considered politically suspect by the Franco regime after the 1936-39 civil war

Some 3,000 reported cases of alleged stolen children have been reported, but prosecutors have closed all but a handful of investigations

In 2013 María Gómez Valbuena, an 87-year-old nun facing two charges of kidnapping and falsifying documents, died before going on trial

In 2017 the European Parliament's Committee on Petitions called on Spain to be more proactive, external in attending to victims by creating a special prosecutor and a public DNA bank, and urged the Catholic Church to open its archives to shed light on Franco-era adoptions.

The parents who lost their babies

Dr Vela was investigated briefly by police in 1981 when a magazine called Interviú published interviews with women who claimed they had been cheated of their babies after giving birth at San Ramón. They said they had been told that their children had died and had been immediately sent for burial.

The gynaecologist left San Ramón in 1982, the police inquiry led nowhere, and the chapter seemed to have closed. In recent years victims began to reach out to each other on the internet, and from 2010 Spanish media began to run follow-up stories.

As well as the trial in Madrid, Dr Vela is also being investigated in connection with the alleged disappearance of a baby born at his clinic in 1971.

Dr Vela was confronted by the BBC's Katya Adler in 2011.

Fuencisla Gómez and her husband, Fernando Álvarez, now bitterly regret accepting that their first-born daughter had died of heart problems without seeing her body.

Coffins exhumed in some stolen baby cases have proven to hold unrelated children or even adult bones.

'That isn't my son'

Such allegations are by no means limited to Dr Vela's two-decade stint in charge of the San Ramón clinic.

Agustina Fuentes and Eusebio Caballero say they never saw their baby boy again after being told he had died three days after a complicated birth at Madrid's La Milagrosa hospital in 1981.

"I was watching him in the incubator through the window each day," recalls Mr Caballero. "He didn't have any tubes attached to him. Then on the third day they said he had died an hour and a half ago." He describes having to fight to see the body.

When he was finally shown a baby, Caballero said: "That isn't my son. I've been looking at him for three days."

The couple have since discovered that no record of their son's birth exists in the Madrid civil registry. They reported their suspicion that their son had been stolen, but prosecutors shelved the investigation.

Some 3,000 similar cases have been reported in the past decade, but only a handful have led to fully-fledged, investigations as courts cite a lack of evidence due to the time elapsed.

Inés Madrigal wants the trial to mark a turning point for others, for the authorities to reopen investigations. But for herself she is not optimistic.

"I know that Eduardo Vela is not going to tell me what I want to know, which is where I come from."

- Published18 October 2011

- Published1 July 2017