Italy warns EU partners on migrant deal ahead of summit

- Published

The EU is still struggling to intercept migrant boats off Libya

The Italian government says it will not sign up to an EU plan for tackling illegal migration to Europe if it does not make help for Italy a priority.

The leaders of 10 member states plan to meet in Brussels on Sunday in a push to tighten border checks and stem the flow of non-EU migrants inside the bloc.

Four Central European states - critics of EU policy - will boycott the talks.

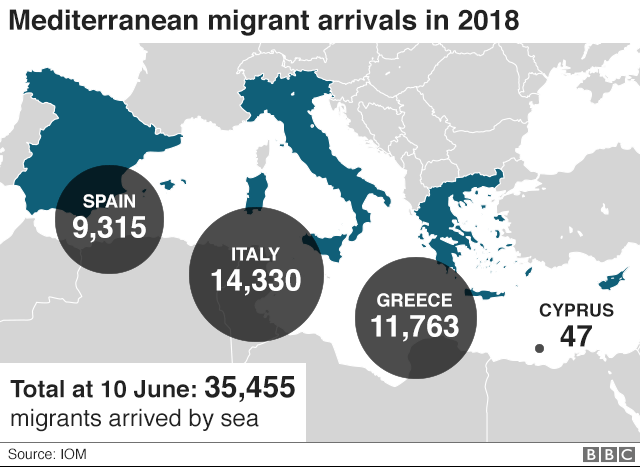

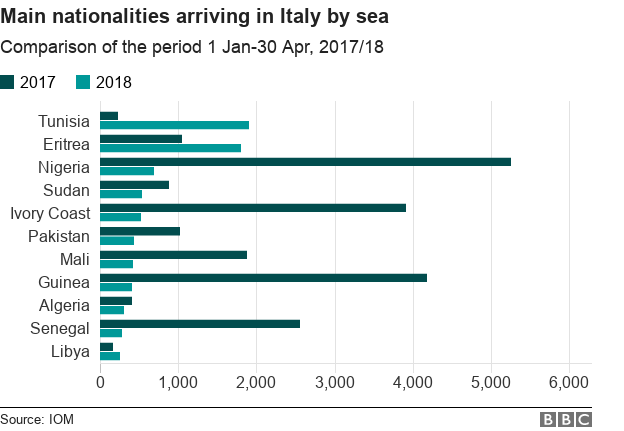

Italy is now the main arrival point for boatloads of migrants - mostly Africans fleeing chaos and violence in Libya.

But Italy has now refused to let in 226 migrants rescued by the German charity Mission Lifeline off Libya.

And last week Italy's refusal to let in 630 migrants aboard the rescue ship Aquarius triggered a diplomatic row with France. The new Italian government accuses charities of undermining EU efforts to curb the influx of migrants.

"We need help now," Italy's right-wing Interior Minister Matteo Salvini said.

"If we are going to Brussels to receive the HOMEWORK already prepared by the French and Germans... the prime minister would do better to save the cost of the trip," he tweeted.

Where are the tensions in the EU?

Sunday's talks come amid serious divisions in the EU over migration and asylum, overshadowing an EU summit to be held on 28-29 June.

The Visegrad Group - Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary - refuse to take in any refugees from Italy or Greece.

Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban said Sunday's summit was "against the normal customs of the EU", so the Visegrad Group would not attend.

Earlier it appeared that Italy too might boycott Sunday's talks. Mr Salvini's warning was prompted by the leak of a draft declaration which, according to Italy's Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, has now been withdrawn.

"I just got a call from [German] Chancellor Angela Merkel, worried about the possibility that I might not attend," Mr Conte wrote on Facebook. "The chancellor clarified that there had been a 'misunderstanding'. The draft text released yesterday will be shelved."

The migration issue is also threatening Germany's coalition government. Bavarian CSU leader Horst Seehofer backs the tough stance adopted by the Visegrad Group and Austria.

A long-time ally of Chancellor Angela Merkel, he objects to her "open door" policy which let more than a million asylum seekers enter Germany in 2015-2016.

Why the tough words from Italy?

Mr Salvini, a Eurosceptic, heads the anti-immigration League party, which accuses the EU of leaving Italy to struggle with an unfair burden of asylum claims.

Italy's new coalition government wants to deport half a million undocumented migrants, many of whom are housed in squalid reception centres. More than 600,000 have reached Italy from Libya in the past four years.

The Italian coastguard brought more than 500 rescued migrants to Sicily on Tuesday

Speaking on Italy's Rai national TV, Mr Salvini said it was "unacceptable" to be told "we will help you in one or two years, while you keep those who arrive and we will send you others".

Prime Minister Conte says measures to curb the flow of migrants to Italy from North Africa are the priority - not transfers of migrants from one EU country to another.

Among them are refugees from the war in Syria or other conflicts, who generally have a right to asylum.

Why doesn't the EU stop the boats coming?

Italian warships are spearheading Operation Sophia, an EU anti-smuggler mission, external patrolling a vast area off the Libyan coast.

The EU has stepped up co-operation with the Libyan coastguard to intercept migrant boats. But people-smuggling gangs have flourished in Libya's chaos, charging desperate migrants thousands of dollars per head.

The EU Commission has proposed "regional disembarkation platforms" in North Africa, where the UN and other agencies could screen those who have a genuine claim to asylum in Europe. Those not eligible would be offered help to resettle in their home countries.

But processing centres outside the EU must not become a "Guantanamo Bay" for migrants, EU Migration Commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos warned.

The EU also aims to beef up its Frontex border guard force to 10,000 staff by the end of 2020.

The EU's controversial Dublin Regulation, external states that an asylum seeker's claim should usually be handled by the country where he/she first arrives.

The regulation - currently under review - enables EU countries to deport asylum seekers to the country where they first landed. Italy and Greece object to that policy, saying they are shouldering an unfair burden.

- Published20 June 2018