Daniel Cordier: France's last Resistance hero from World War Two

- Published

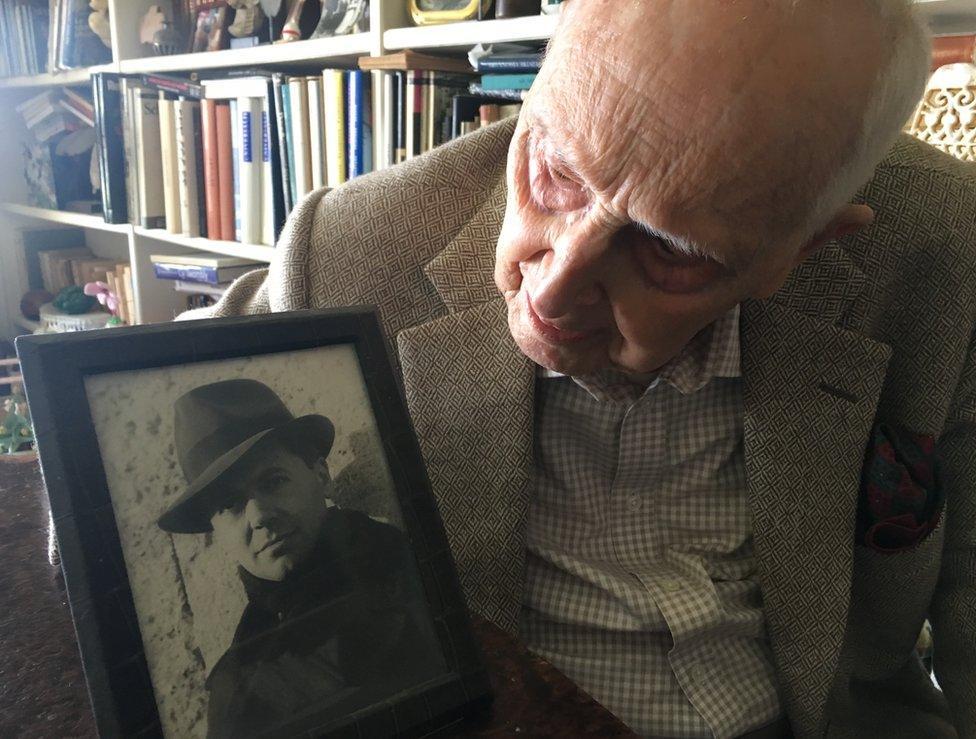

Daniel Cordier eventually wrote a biography of Moulin (pictured) - the man he served for the final year of the Resistance leader's life

When Daniel Cordier was parachuted into Nazi-occupied France to meet Resistance leader Jean Moulin he had no idea he would become Moulin's closest companion.

Cordier was sent over in July 1942 on the orders of General Charles de Gaulle, based in London. But he did not even know Moulin's name.

Cordier was under instructions to report to a certain "Rex" at an address in Lyon.

"Rex" would vet him, then assign him to another Resistance leader, Georges Bidault. That was what Cordier had been told.

What happened instead was the turning-point in Cordier's life. It would also be a year that led to Moulin's death.

Meeting Moulin

"When I went to the address, I saw 'Rex' and he told me to meet him at a certain restaurant that evening near the opera," Cordier recalls.

"So we met up and we talked late into the evening. And then we walked along the quays by the Rhone, and when we got to where 'Rex' was living he said to me: 'Remember the street number. Tomorrow you turn up here at seven. You are now my personal assistant'."

Moulin, given the task of uniting the Resistance by the leader of Free French forces in London, was killed on 8 July 1943. He had been betrayed to the Nazis, then tortured, and he died on board a train to Germany.

Remarkably, 75 years later, it is still possible to hear living testimony from the man who served him so intimately in the last crucial period of Moulin's life.

At 97, Daniel Cordier is one of only a handful of people still alive who bear the title "Compagnons de la Libération" (Companions of the Liberation). And of these few heroes, he is by far the most important.

Daniel Cordier left to join the Free French in 1940 and returned in 1942

He tells his story in the charmingly disordered living room of his flat overlooking the Corniche in Cannes. Piles of art books are a reminder of Cordier's later incarnation as a leading Paris gallery-owner.

Escape to London

Born into a wealthy family in Bordeaux, in his teens he adopted the far-right politics of his milieu. He was a member of the ultra-nationalist Action Française and sold its newspapers on street corners. By his own account he was "fiercely anti-Semitic".

But then came the German invasion of 1940, and the French collapse. With his mother and stepfather he listened to the radio address made by Marshal Philippe Pétain, urging the French army to surrender.

"As my mother collapsed into my stepfather's arms, I raced upstairs and flung myself on my bed, and I sobbed. But then it must have been half an hour or so later, I suddenly drew myself up, and I said to myself: 'But no, this is ridiculous.

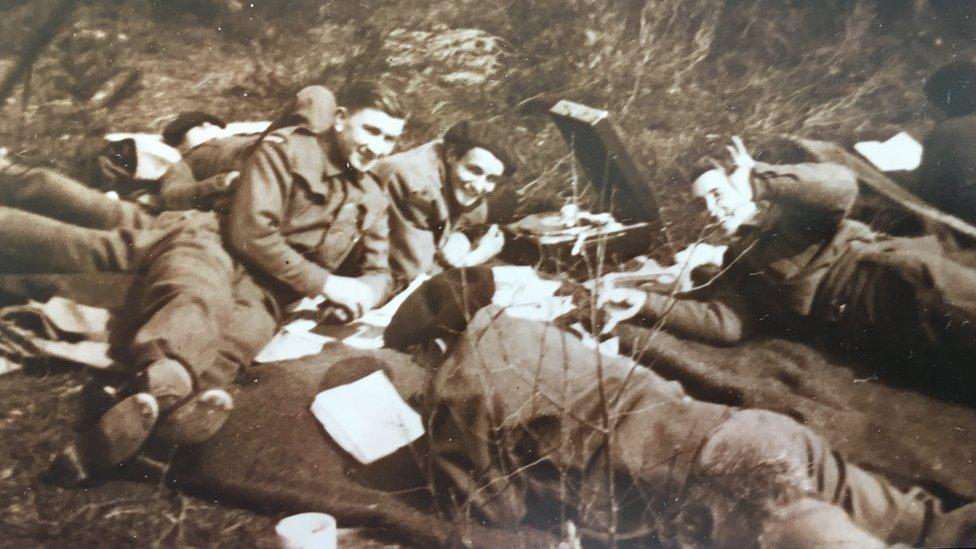

Cordier (R) went through training in Britain and was chosen to join the secret intelligence arm of the Free French

"[Pétain] is just a stupid old fool! We have to do something. But what? I did not know."

What Cordier did, with help from his wealthy stepfather, was to board a ship from Bayonne which took him to England and, though he did not know it at the time, to De Gaulle's Free French.

His first glimpse of De Gaulle came a few weeks later, when the general came to review recruits at the Kensington Olympia hall in London.

"This immense figure appeared in the doorway, and he had to stoop in order to get through without knocking off his képi," said Cordier.

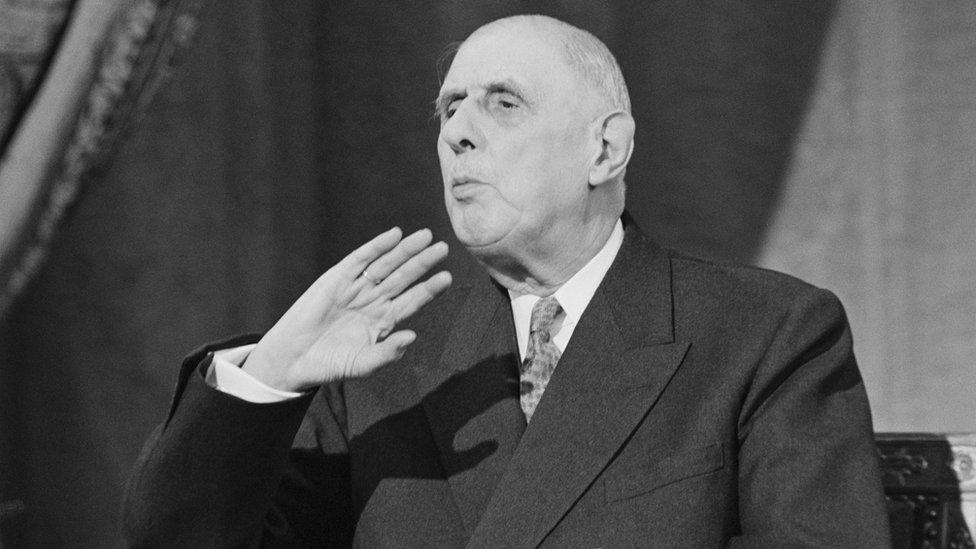

Gen de Gaulle escaped to London to form the French government in exile

"I will never forget his first words: 'Gentlemen, I will not congratulate you for having come here. You have merely done your duty!'

"Not a word of encouragement! I thought it was an extraordinary thing to say!"

Face to face with Nazi anti-Semitism

Daniel Cordier went through training and was selected to join the secret intelligence arm of the Free French. That was how he came to play his part in Moulin's mission to unite the Resistance.

For a year he was Moulin's right-hand man, writing his correspondence and liaising with other leaders. In May 1943 he was on guard outside the building in Paris, when the first meeting of the united Resistance chiefs took place.

It was in Paris that another important moment was to take place in Cordier's life: the shedding of his anti-Semitic youth.

Based in Lyon, which was not at the time occupied by the Germans, he had not yet come face to face with the anti-Jewish legislation.

"I was at the Arc de Triomphe, and walking to a cafe where I had arranged to meet my courier. And there coming up the Champs-Elysées towards me were a man of about 60 and a boy of 13 or 14.

"And over their chest they had a board on which was written the single word 'Jew'. It was the most shocking thing I had ever seen. And I had just one thought: to go to them and embrace them and ask forgiveness."

Before he died in 2012 Resistance hero Raymond Aubrac spoke to Hugh Schofield about Jean Moulin's arrest

Moulin was betrayed a few weeks later. Cordier stayed in France until 1944 and then came back to England, where he learned for the first time the true identity of his colleague, friend and hero.

Life after Moulin

"I admired Jean Moulin from the moment I first saw him. He had an elegance, and a kindness, and also a huge capacity for work. In his view, he was the Resistance," said Cordier.

"I hope in my own small way I was able to serve him as he wanted."

A picture of Jean Moulin sits on Daniel Cordier's bookshelf at his home on the French Riviera

Moulin's influence on him has lasted through the years. It was the Resistance chief who in the war introduced Cordier to painting and art, leading to his subsequent career as a collector and dealer.

And many years later it was to defend Moulin's honour that Cordier took the role of historian and wrote his monumental biography of the man. In the 1970s insinuations had begun to appear that Moulin had been a Communist agent.

"I knew it was not true. But to prove it, I had to go back to the records," he says.

In the twilight of his life, Cordier says he is happy because he is "free".

A few years ago he came out as a gay man, a step that would have been "utterly unthinkable" when he was young.

"What always counts most is the truth," he says.

- Published2 December 2017