Can Nato survive US President Donald Trump?

- Published

This is a Nato summit like no other. The difference is in large part due to one man - Donald Trump. Under his watch, periodic tensions between the US and many of its allies have turned into fault-lines that could, if allowed to widen, place a question mark over the future of the alliance itself.

What is Nato for?

From its inception, Nato was a defensive military alliance intended to deter any attack by the then Soviet Union.

Once the Cold War was over, Nato set about what it saw as its new tasks: an attempt to spread stability across Europe by welcoming in new members, by establishing a wide range of partnerships with other countries but also by using force on occasion - notably in the Balkans - to prevent aggression and genocide.

But the alliance has always been more than just a military organisation.

It is one of the central institutions of "the West", part of a whole range of international bodies through which the US and its allies sought to regulate the world that emerged from the defeat of Nazism in 1945.

But fundamentally, Nato is an alliance of shared values and transatlantic unity. And this is why Mr Trump's arrival in the White House is proving so disruptive.

Is the transatlantic bond unravelling?

Superficially, at least, the growing tensions between the US president and many of his Nato allies is about money.

Burden-sharing, as it is called, has long been a headline issue at Nato summits.

Mr Trump is not the first president to stress this issue.

But in terms of both style and substance he represents something new.

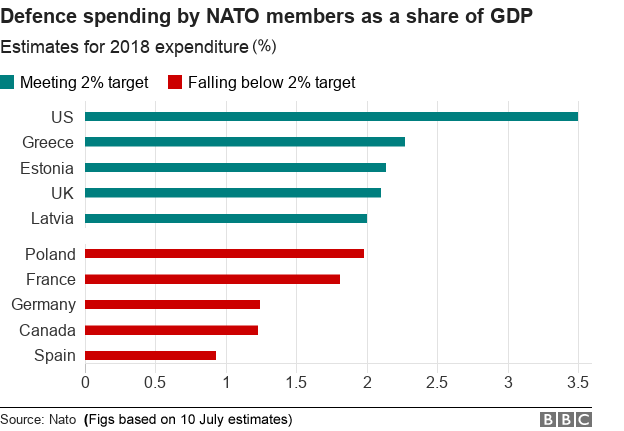

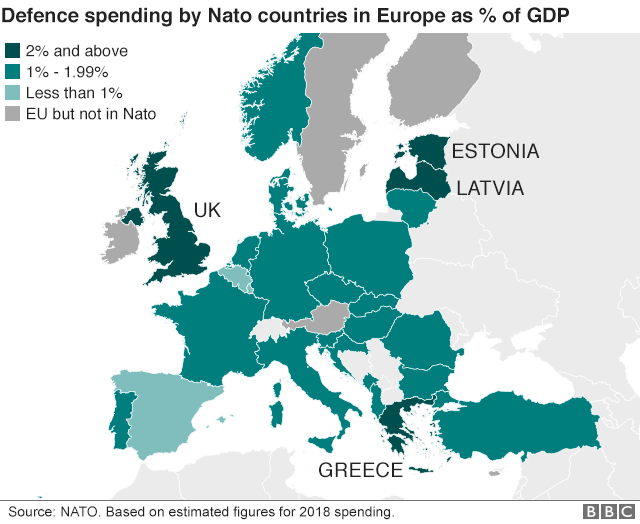

The debate focuses around the target agreed by all Nato members that defence spending should reach 2% of GDP (gross domestic product, the total value of goods produced and services provided) by 2024.

Spending is certainly up in many countries.

Mr Trump can take some credit for that.

But many allies may still struggle to reach the benchmark target.

For President Trump, Germany, one of the richest of Washington's partners, is the greatest offender.

Earlier this month, in remarks directed at the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, he said: "I don't know how much protection we get from protecting you."

Noting that Germany negotiated gas deals with Russia, he added: "They pay billions of dollars to Russia and we're the schmucks paying for the whole thing."

Questioning the value of Nato to the US itself is something new and deeply worrying to many of Washington's partners.

How serious is the Russian threat?

The strategic challenges facing Nato are changing.

They are, at one and the same time, more complex but less easily defined.

They range from a resurgent Russia to information- and cyber-war, from terrorism to mass migration.

Russia has shown itself willing to flex its military muscle in places such as Georgia

Even the Russian threat has changed. This is not the Soviet Union of old.

The threat is less huge Russian tank armies surging westwards but a whole range of strategies from hacking to cyber-attacks to information operations, all intended to throw Western democracies off-balance.

Western governments clearly believe Russia is willing to resort to assassination too - witness the murder of Alexander Litvinenko in London in 2006 and the attempted murder of the former Russian agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia Skripal in Salisbury, Wiltshire, earlier this year.

Russia is a relatively weak country but it is willing to use its military muscle - especially close to home in Georgia and Ukraine - to secure its own strategic interests.

Of course, Russia sees Nato's expanding boundaries as a threat to its security.

Can Nato survive Trump?

Mr Trump's bluntness is, at one level, refreshing.

The US is a superpower with strategic interests all over the globe.

The Russian threat is now different - to meet it does not require the mass forces of the past.

Europe probably should be able to provide more of its own defences.

Donald Trump is expected to meet Vladimir Putin in Helsinki shortly after the Nato summit

Indeed, for all the Trump rhetoric, the reality is that the US is now more engaged militarily in Europe than it was just a few years ago.

Key figures in this administration, not least Defence Secretary James Mattis, are keen supporters of the Atlantic alliance.

But does Mr Trump himself share the values of Washington's European and Canadian partners? Many would say he does not. Does he recognise the value of an alliance such as Nato to the United States? Again, for many the answer would be no.

Mr Trump goes on from this Nato summit to meet his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin. This encounter has many Nato allies spooked. What might the president give away? What message will Moscow take from Nato's difficulties?

Nato diplomats were resigned to negotiating the ups and downs of one Trump presidency. Now, there are genuine fears that a second Trump term could leave Nato marginalised and its transatlantic spine deeply damaged.

- Published28 May 2017

- Published10 July 2018