World Cup 2018: French optimism resurgent

- Published

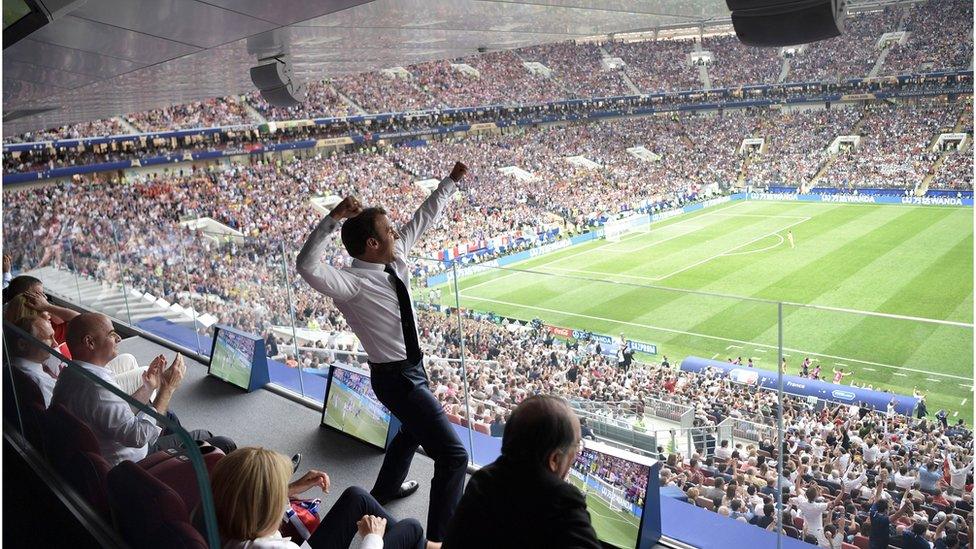

Fans celebrate as France wins World Cup 2018

Sport proves nothing. Everyone knows that.

Winning the World Cup doesn't mean that France is poised for a surge of self-confidence, resulting in higher economic growth and contentedness for all.

Nor does it mean that social divisions are suddenly healed. In 1998 France won the Mondiale for the first time, and pundits prematurely proclaimed the emergence of a new multi-colour nation. No-one is so naïve this time round.

Victory does not even have any particular message for the health of French football.

True, the system has produced a prodigious new generation of players - many like the young superstar Kylian Mbappé born in the high-immigration suburbs or banlieues. And by general consensus, Didier Deschamps as manager has been a soft-spoken triumph.

But let's face it: any one of half a dozen countries could have won the World Cup. In the end victory is also down to luck and timing, and whether a ball twists inside or outside a goalpost.

Have these footballers restored pride to the streets of France?

It was France who got the breaks. But as everyone knows, that proves nothing.

And yet…

Tonight, as the country swarms out of the bars and on to the streets to celebrate, those are precisely the three prime emotions: confidence, unity and footballing pride.

For a quarter of a century France has been losing its self-confidence. And then in the last year - since the election of President Emmanuel Macron - there came a turnaround.

Well of optimism

President Macron's election has, perhaps, helped kick-start French change

It would be silly to attribute this to Mr Macron alone - he is certainly not a universally popular figure. Perhaps better to see the president as personifying a change in society as a whole, as a younger, more adaptable generation takes the reins.

Whatever the case, no-one can mistake an air of cautious optimism about France today that is as welcome as it is unusual. Quite possibly this is aided by comparison with other countries - say the UK - that seem to the French to be on a downward curve.

But pleasure at the misfortune of others is still pleasure - and for the first time in years, people in France appear to feel (relatively-speaking) good about themselves.

Added to this is a new sense of unaggressive but unembarrassed patriotism in France that probably owes a lot to the terrorist attacks of the last three years.

The tricolour flies from the windows of homes; enlistment for the armed forces is up; the far-right no longer pretends to a monopoly on the symbols of the nation.

Rallying the nation

Will this rallying around an ethnically diverse football team extend to French society at large?

In football, the country has found it easy to rally behind a team that projects both ethnic diversity and frank patriotic fervour. Kylian Mbappé - child of Cameroonian-Algerian parents - told Le Monde that all he wanted to do was "embody France, represent France and give my all for France".

Striker Antoine Griezmann made a similar outburst at a news conference on Friday, telling journalists that "we should be proud to be French. Life in France is good! We eat well. We have a beautiful country and a beautiful national team".

Long gone, in other words, are the days of surly silences during the singing of the Marseillaise.

Indeed, victory in Russia draws a final line under a dark period of French football, whose low point was the notorious "strike on the bus" in South Africa eight years ago. It has been a long steady fightback under Deschamps, but today the national side is securely back at the top.

In the last six World Cups, France has played three times in the final, and won twice. That is no mean achievement, and a tribute to the way the nation nurtures and keeps its talent. The banlieue wonderboys may leave for rich clubs in England and Spain, but they come back home when it counts.

- Published16 July 2018

- Published15 July 2018

- Published14 July 2018