Slavery memorial highlights Portugal's racism taboo

- Published

This statue of emancipation was built on an island off Senegal that was used by slave ships from Portugal, France, England and the Netherlands

Portugal's first attempt to commemorate its long history of slavery with a monument has inflamed passions over how the country should confront its colonial past and face up to its multiracial present.

The memorial to millions of victims of slavery remains not just unbuilt but undesigned, even though residents voted last December to have it erected on a pleasant waterside promenade named Ribeira das Naus.

Slave ships unloaded their human cargo there as part of an Atlantic trade that lasted 400 years until the 19th Century. Not far away stands Lisbon city hall, on the site of a former slave jail where Africans were held until their owners paid taxes on their human chattels.

For a nation that glorifies its explorers and navigators, examining its colonial past is divisive. And Portugal has traditionally prided itself on being colour-blind.

From slavery to modern racism

"We want this monument to bring life to the debate around racism today," says Beatriz Gomes Dias, whose association of African descendants, Djass, is promoting the monument.

"Portugal needs to recognise that slavery is not something that was cleared up in the past. There is a clear line between slavery, the forced labour that continued afterwards, and the racism that is now going through society."

The monument is yet to be built at this waterside spot in Lisbon

Some white Portuguese observers argue the country does not have a racism problem, however.

"Anyone who has any knowledge of Europe has to agree with us: Portugal is probably, if not definitely, the least racist country in Europe," the academic and founder of the International Lusophone Movement, Renato Epifânio, wrote last year.

Writer and historian João Pedro Marques accepts that descendants of Africans have a right to remember their people's suffering. But he argues that activists are exaggerating Portugal's role in the slave trade and distorting its colonial history for political purposes.

"I think that those who are campaigning against racism want to substitute one biased view of events with an even more biased one," he said.

'Pride in colonialism'

Ms Gomes Dias says black Portuguese activists are attempting to "challenge the mainstream narrative of Portuguese identity".

"There is no place in the Portuguese imagination for blacks. People of African descent are not recognised as part of Portuguese society," she said.

Last year Portuguese President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa visited Senegal's House of Slaves last year - but made no apology on behalf of the state

The way Portugal's "age of discovery" is taught in schools creates a misguided sense of pride in colonialism, she believes.

"We want to confront this idea of discovery, and enlarge it to include all people's histories. We cannot say that violence, oppression and genocide are a positive thing. We need a real debate about our common past," she said.

Age of oppression - and discovery

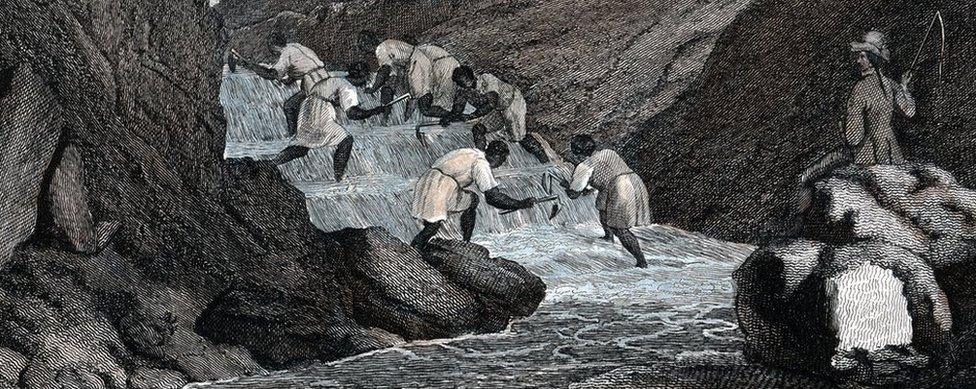

This 1814 print shows slaves searching for gold in Brazil when it was a Portuguese colony

Until Portugal's participation in the slave trade ended in 1836, Portuguese and Brazilian ships transported close to six million slaves over a 400-year period, almost half the total number of people taken across the Atlantic as slaves

Most slaves were captured in Africa but they also included Chinese from Portugal's former colony of Macau

Controversy also surrounds the future of a long-planned Lisbon museum dealing with Portugal's period of overseas expansion

Initially named the Museum of Discovery, more recent names include Discoveries, Inter-culturality and most recently Museum of Voyage

In June more than 100 black activists and intellectuals urged the government not to confuse slavery and invasion with discovery or maritime expansion

Under Portuguese law it is illegal to gather race-related information, so data is hard to come by.

But Cristina Roldão, a sociological researcher at Lisbon's IUL university, says that black Portuguese citizens or residents do not, in reality, enjoy equality.

Young black people between the ages of 18 and 25 are only half as likely to go to university as white Portuguese, according to research she has worked on. And the incarceration rate in Portugal is 15 times as high for people with African origins.

Being black and Portuguese

Born to parents from Cape Verde in Portugal, Dr Roldão has Portuguese citizenship, but she cites an "unfair" 1981 law that prevents some of African descent from being considered Portuguese despite being born in the country.

"Portugal continues to see non-white people as separate to its national identity," says Mamadou Ba of SOS Racism Portugal.

He was born in Senegal and has lived in Portugal for more than 20 years, and says the law means "children born in Portugal are considered foreigners in their own country".

Campaigners call for reforms to citizenship - which is not granted to those born on Portuguese soil

"Being black in Portugal means experiencing economic, cultural, social and political subordination. To be black in Portugal is to be confronted permanently with symbolic and physical violence in everyday life," he said.

Writer João Pedro Marques agrees that racist people exist in Portugal, but he insists it does not have a problem with racism.

Under the dictatorship of Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, Marques says that historic figures were "heroes without defect or blemish". Now he complains that the "politically correct far left have pushed us to the opposite extreme and our ancestors have become the worst in the world".

It has become a debate about far more than a monument to victims of slavery.

But for campaigner Beatriz Gomes Dias, it is proof that the monument is needed.

She and her fellow activists are now seeking an artist who can capture the historical suffering and the issues of race in today's Portugal.