Papal visit: What sort of welcome awaits Pope Francis in Ireland?

- Published

The Irish Republic Pope Francis will visit is a country transformed since his predecessor, Pope Saint John Paul II, travelled there in 1979.

Back in the 1970s, almost 90% of Catholics there would attend weekly Mass. Divorce, abortion and contraception were against the law.

The Roman Catholic Church enjoyed such dominant cultural status that the largest gathering of Irish people in history occurred in Phoenix Park, Dublin, when Pope John Paul II came to visit in 1979. Almost 1.5 million were there.

Fast-forward four decades and, as Pope Francis prepares for only the second papal visit to the country, this one-time jewel in the Catholic crown of Europe is fast shifting away from its once rock-solid allegiance.

Crowds will still come. Indeed, 500,000 people are expected to attend a Mass celebrated in Phoenix Park and 2,000 police officers will be on duty in Dublin. But times have changed.

Huge crowds greeted Pope John Paul II during his 1979 visit to Ireland

In May, the Pew Research Centre suggested that Europe, where Catholicism has been based for most of its history, had become one of the world's most secular regions, with the majority neither affiliated to, nor attending, a church.

The survey coincided with the Irish referendum on abortion, when almost two in three voters opted to repeal the constitutional amendment that had equated the right to life of the unborn with a mother's right to life, effectively banning abortion in the Republic.

When added to Ireland's 2015 vote to legalise same-sex marriage - 62% in favour and the first country in the world to do so by popular vote - it's possible to attribute declining religious affiliation in Ireland to the external forces of secularism.

But religious faith and attendance at Mass have been diminished from within: scandal upon scandal has ravaged the Church's moral authority.

A recent referendum in the Irish Republic went in favour of ending the country's abortion ban

Take Michael McCloughlin who, as a 22-year-old baritone, was one of the soloists when Pope John Paul II visited the Republic in 1979. Thirty-nine years later, he still speaks of the visit with infectious nostalgia.

"It was like the biggest rock gig that you ever wanted to be at in your whole life," he says at his home in County Tipperary. "This was it and you had a backstage pass."

But he won't be coming out for Pope Francis. He says that the clergy were not only wicked in their abuse of children, they compounded their wrongdoing by silencing their victims and protecting each other.

"These were people who were in positions of incredible trust and they betrayed that trust not only by the acts that were perpetrated on children but there was the widespread covering up of it by the hierarchy in the Church as well."

Michael McCloughlin has now walked away from the Church and his faith. But his words could apply to almost any region of the world where the Roman Catholic Church operates.

The United States is still reeling from last week's report, presented by Pennsylvania's Attorney General, Josh Shapiro, that detailed credible allegations against 301 members of the clergy in six of the state's dioceses. More than 1,000 children are said to have been abused.

At a news conference, Mr Shapiro said, "They protected their institution at all costs. As the grand jury found, the Church showed a complete disdain for victims."

The report, 884 pages long, represents a forensic and devastating analysis of abuse in Pennsylvania. The allegations are shocking even for those who have become accustomed to reading stories of predatory abuse.

One girl returned to church attendance after having her tonsils removed. She was raped. Another priest raped a girl, got her pregnant and then arranged for an abortion.

Priests took photographs of an abused boy and added them to a collection of pornography that was then shared with others.

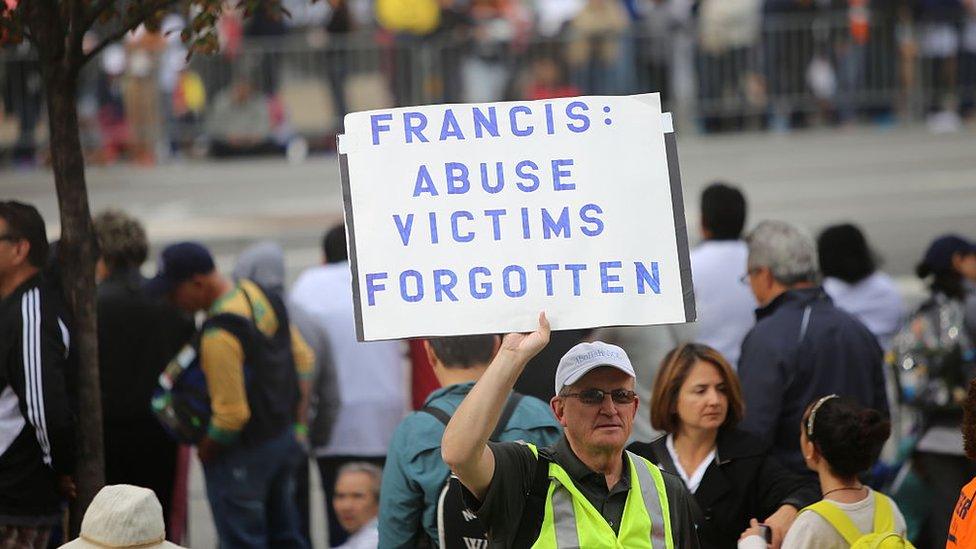

In America, the Church has been criticised for its alleged lack of response to the abuse of children by clergy

In May, Pope Francis accepted the resignation of three Chilean bishops, including the Right Reverend Juan Barros, who was accused of covering up sexual abuse committed by a priest in the 1980s and 1990s.

Pope Francis said that he had made "grave mistakes" by originally defending Bishop Barros, who denies any wrongdoing. And all of Chile's 34 Roman Catholic bishops then offered their resignations.

Europe, North America, Latin America - the places are different, the allegations often the same.

And, with this global blizzard of sexual abuse allegations, Pope Francis took the step of issuing a letter, To the People of God, at the beginning of this week as he prepares to visit Ireland.

It was rich in compassion and repentance. He condemned cover-ups, clericalism and complicity. But one line stood out because it spoke to the challenge facing the Church.

Pope Francis wrote: "Looking back to the past, no effort to beg pardon and to seek to repair the harm done will ever be sufficient."

Entire generations have been manipulated, exploited and abused and they are unlikely to return to the fold.

Efforts are being made to protect children and prevent abuse - but while his letter is deep in compassion, some believe it contains little in the way of policy.

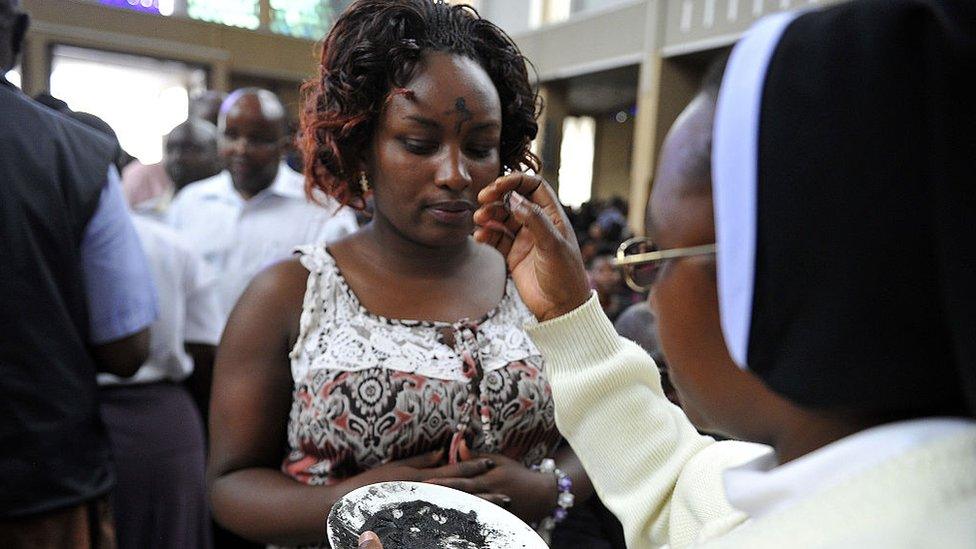

While the number of practising Christians is falling in the West, the faith is burgeoning in Africa

A century ago, 80% of Christians lived in North America and Europe; that figure is now down to 40%. But the figures for both Protestant and Roman Catholic churches elsewhere are much more buoyant.

In 1900, Africa had just 10 million Christians out of a continental population of 107 million, about 9%. Today, the Christian total stands at 360 million out of 784 million, or 46%.

By 2025, 50% of the world's Christian population will be in Africa and Latin America, with another 17% in Asia.

But as Pope Francis prepares to depart on his aircraft, Shepherd One, on Saturday morning, the religious landscape in Ireland is clear.

Marie Collins, who was abused by a hospital chaplain in Dublin as a child and sat on the Vatican's Commission for the Protection of Minors until she resigned last year, said the Pope faced a daunting task this weekend.

"Pope Francis has to do more than just offer compassion. He must outline some concrete proposals for dealing with child abuse that now threatens the survival of the Church around the world," she said.

It seems the biggest challenge for the Church in Ireland is not the power of secularism, from without, but the task of establishing moral integrity and moral accountability, from within.