Russia's Putin embraces higher pension age but softens blow

- Published

Protests have taken place across Russia and more are planned despite the concession to women

For a long time Vladimir Putin distanced himself from Russia's pension reform.

It was always expected to be highly controversial and the idea was for the government to propose the tough reform and take the flak.

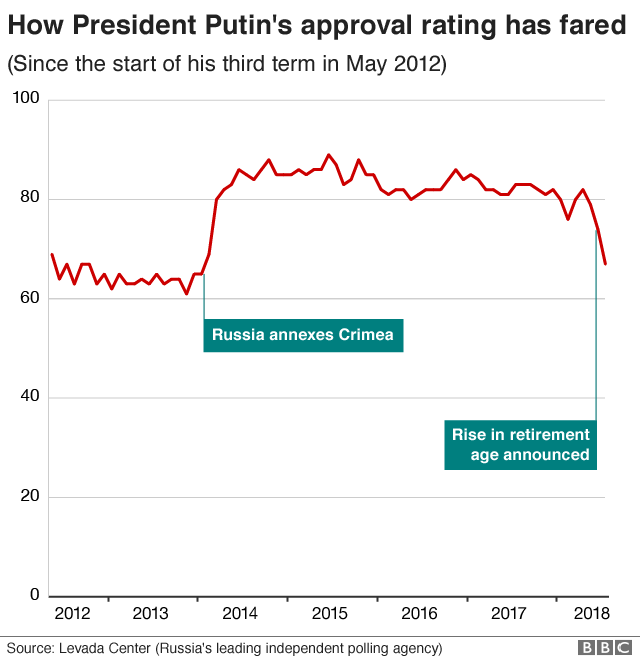

But the street protests grew and President Putin's approval rating fell, regardless. So now, as if on cue, he has ridden to the rescue - cast as Vladimir the Benevolent, stepping in to soften the blow.

Any notion that he would simply scrap the reform, or overhaul it significantly, was soon scotched.

From the start of his speech, simulcast on all state TV channels, Mr Putin went to great lengths to explain that raising the retirement age was essential.

Acknowledging that he had once promised never to take this step as president, he argued that times - and the economic environment - had changed.

'We cannot delay'

Too many pensioners and too few workers were putting an intolerable pressure on state finances. If nothing changed, the president warned, the system would first crack and then collapse.

His tone veered from kindly and sympathetic - calling viewers his "dear friends" and stressing that he shared their concern - to stern.

"We really can't delay any more," Mr Putin insisted. "That would be irresponsible."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

He cast pension reform as a matter of national security.

The president did offer some mild relief from the initial proposal for Russian women.

As Russia "cares" for its women, he said, they would have to work only five extra years before retirement at 60, instead of eight.

That can be cut further, mind you, if they have extra children - basically producing extra workers to contribute to the pension pot.

On the other hand, those mothers will probably have to stay at home to care for their bigger brood. At the moment, many grandmothers help raise children once they retire at 55. Under the new system, they would be working.

But the biggest bone of contention is male workers. Vladimir Putin left the new retirement age for men at 65, a five-year increase.

His argument is that life expectancy has leapt up under his rule, which is certainly true compared to the dire post-Soviet crisis of the 1990s.

But Russian men still only live to 67 on average. Under the new system a huge number would not survive to collect their pension. More money, then, for that "cracking" system.

Will this calm the anger?

The Kremlin says Mr Putin has intervened on this issue because of its importance, not to boost his flagging rating.

His spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, told the BBC it was a "brave step, in Putin's style" and state TV has now gone into overdrive promoting it and the pension reform.

However, supporters of opposition politician Alexei Navalny have reacted to the speech by posting fresh calls to a protest on 9 September.

Mr Navalny himself was sentenced to 30 days in custody this week, a step he argues was meant to hinder preparations for rallies against the reform across the country.

And on the streets, Russians' initial reaction has been cool.

One woman, Irina, blamed foreign policy and sanctions for the lack of cash in the pension pot.

A man called Sergei said he feared there would be no money at all by the time he reached retirement.

The risk for Russia's president, of course, is that while this unpopular move could once be pinned firmly on the government - it's now very much Vladimir Putin's proposal.

- Published5 July 2018

- Published29 August 2018