Venezuelans escape to Spain and ask to return old favour

- Published

"Caracas became like Galicia under Franco when I was a boy, when there was rationing"

Once, Spaniards fleeing repression and poverty in Francisco Franco's dictatorship found themselves building new lives in Venezuela, given refuge by their cousins across the Atlantic.

Now, Venezuelans are asking them to return the favour.

A shared language and cultural heritage draw Venezuelans escaping from hardship under the socialist government of President Nicolás Maduro.

But many new arrivals say Spain's authorities are failing to recognise them as genuine refugees, forcing them into legal limbo and black economy jobs.

Venezuelans have topped the list of asylum requests in Spain for three years, but only a tiny fraction are granted refugee status: just 15 out of 12,875 last year.

The UN says that 208,333 Venezuelans were living in Spain by April this year - but August figures from Spain's labour ministry show that fewer than 40,000 are officially registered to work.

Many of the rest disappear into the black economy.

Most Venezuelans arriving at Spanish airports claim to be tourists. In reality many have sold everything just to get there.

'Not here to beg'

"Venezuela received Spaniards with no questions asked, regardless of whether they had money or papers. The least we expect is to be received in the same way," says Luis Manresa, a Venezuelan politician from the opposition party Acción Democrática.

He fled to Madrid in 2011 because, he says, he had received threats from the government and was about to be arrested on trumped-up charges.

But he says: "Venezuelans don't come here to beg; they come to work."

Volunteers in Mr Manresa's support network say 200 to 300 families arrive in Spain every week, some of whom end up being held at the airport because they lack papers - or cannot convince the police that they are planning only to visit.

From schoolteacher to cleaner

Maria Eugenia Carrillo was enthusiastic about the system of free schooling introduced by Hugo Chávez in the early 2000s. But increasing pressure by her bosses to include political content in lessons bothered her. And then there was the poverty.

"I saw my children sick and hungry, their parents looking for food among the rubbish and diseases like measles running rampant through the school," she says.

"When parents came to pick up their children they stopped asking 'what did you learn today?' and asked instead: 'What did you eat today?'"

"I always dreamed of living and dying in Venezuela."

The 52-year-old teacher says that the political pressure caused her so much stress that her fibromyalgia became more acute - until she decided she had to leave Venezuela, flying to Madrid in October 2017.

Without official papers, she has no chance of working as a teacher, and is cleaning homes for cash.

"I always dreamed of living and dying in Venezuela," she says. "I even had a beach house until a Chavista [a supporter of Venezuela's government] took a shine to it and moved in. I couldn't do anything. I was paralysed by the fear of being arrested."

William Cárdenas, a lawyer and former Venezuelan diplomat now in Madrid, says Spain's government could use an existing law designed for cases of a massive influx of displaced people from a foreign country.

But Spain says Venezuelans cannot be considered "displaced" in the same way as refugees fleeing a war zone.

Venezuela's government, meanwhile, claims that the exodus of citizens is the result of a propaganda campaign aimed at bringing down the socialist regime.

"Some of the Venezuelans who left to clean toilets abroad have become economic slaves because they were told it was necessary to leave the country," President Maduro said in August.

Caracas rationing 'like under Franco'

The irony of Spain and Venezuela's reversal in fortunes is not lost on Cándido Soengas, who escaped poverty and dictatorship in 1950s Spain by crossing the Atlantic.

Now, he has been forced to return to Spain, as living conditions unravelled in the Venezuelan capital.

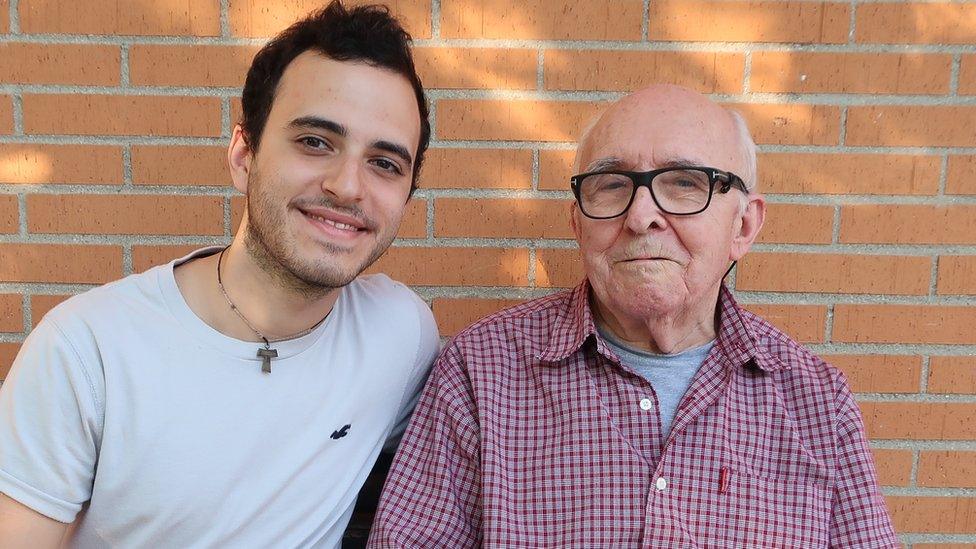

"I never expected to come back," 87-year-old Mr Soengas says in the garden of his Madrid retirement home, reminiscing on the life he and his late wife made for themselves in Caracas.

"I was happy in Venezuela. There were always people about to lend me a hand and when I brought my children up, we wanted for nothing."

"They were good times."

Mr Soengas in his younger days, celebrating a baptism with family in Venezuela

Mr Soengas took a ship to Venezuela in 1956 because he was fed up with the poverty and lack of job prospects in Galicia, in Spain's north-west. He married a fellow Galician immigrant and had a string of small business ventures in Caracas.

As a retired widower, Mr Soengas's health began to deteriorate, and he could no longer get the medicine he needed to control his epilepsy.

"Caracas became like Galicia under Franco when I was a boy, when there was rationing. I would be queuing outside a food store, and then the door closed because there was nothing left."

A year after his return, he was joined in Madrid by his grandson, Jesús Soengas, who says he feared for his life after participating in student protests against the Maduro government.

Jesús, 23, with his grandfather Cándido Soengas - both of whom have moved to Spain

"When I saw how my friends, the people that studied with me, started getting killed by the government, I decided I might be next," he says.

He is fortunate enough to hold a Spanish passport.

Jesús is combining law studies at a Madrid university with shifts as a Deliveroo bicycle courier. "Sometimes, I hardly sleep because of studies and work. But I am lucky to have the possibility of working legally."

While leaving Venezuela was emotionally very hard, his hope is that the experience of exile will one day enable him to return to help rebuild it.

"If I want to build that better country, I have to prepare myself, to study, to see different things and see how democracy works in the real world."

- Published23 September 2018

- Published25 September 2018

- Published23 September 2018

- Published12 August 2021

- Published28 August 2018

- Published25 August 2018

- Published25 August 2018

- Published5 September 2018

- Published25 August 2018

- Published22 August 2018

- Published20 August 2018