Is nuclear disarmament set to self-destruct?

- Published

Are we on the cusp of a new nuclear arms race?

Never has the future of nuclear arms control seemed so uncertain.

At risk is not just the collapse of existing treaties, but a whole manner of interaction between Russia and the United States that has been crucial to maintaining stability over decades.

So what's the immediate problem?

The US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo served Russia notice.

The US is suspending its participation in the important Cold War-era disarmament agreement - the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty as of 2nd February.

Russia, the US insists, has long been in breach of this agreement. And if it does not return to compliance within six months, the US will walk away from the INF Treaty altogether.

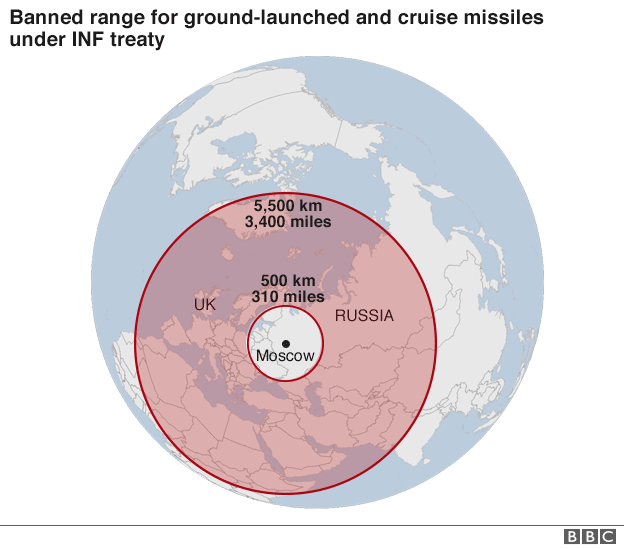

This 1987 agreement with the ex-Soviet Union removed a whole category of land-based nuclear missiles: those with ranges of between 500 and 5,500km (310 and 3,100 miles).

1989: A Soviet SS-23 missile is destroyed, under the INF treaty

Being small, highly mobile, and located relatively close to their potential targets, they were seen as highly destabilising.

In the late 1970s Soviet Russia deployed the SS-20 missile to threaten targets in Western Europe, causing alarm in many Nato capitals.

The US responded by deploying Cruise and Pershing weapons in a number of European countries. But after the agreement, all these weapons were removed and destroyed.

The Trump administration says that a new Russian missile, designated the 9M729 and known to Nato as the SSC-8, breaches the INF Treaty. Back in December, Mr Pompeo gave Russian President Vladimir Putin 60 days to return to compliance or the US would also cease to honour its terms.

Russia insists that it is abiding by the agreement, and raises concerns about Washington's own adherence to the deal.

So who is right?

The Americans say they have powerful evidence that, over several years, Russia has developed and now fielded a missile that falls within the range that is banned by the INF Treaty.

This, by the way, is not a new idea raised by the Trump administration. President Barack Obama too was concerned about what the Russians were doing.

The evidence has been put to Washington's Nato allies and they have all backed the US case. Many of them though are privately not happy to see the US itself withdraw from the treaty, preferring that more time be given to try to reach an accord with the Russians.

Moscow has arguments of its own, asserting for example that US anti-ballistic missile interceptors deployed today in Romania, but soon to Poland as well, could potentially fall into the INF agreement's terms if their warheads were changed.

But such a potential future breach is very different from what the US is charging Russia with having done.

Indeed according to some reports, unnamed US officials are claiming that Russia has already deployed around 100 of the new missiles.

So can the INF Treaty be saved?

Or, to put it another way, does either country really want to maintain the treaty? On the face of it the answer is no.

Statements from Mr Pompeo, and indeed from Nato, hold out the hope that Moscow may change its mind. But it would be a significant climb-down.

And there have been some 30 instances of contacts between US and Russian officials on this subject over recent years.

A last-minute resolution is unlikely.

If indeed Russia is in breach of the agreement, as Nato insists, then it clearly believes that developing a weapon in this category has some strategic value. And there is no hint of Russia backing down.

As far as the Americans and their allies are concerned, the ball is in Moscow's court.

It is the Russian government that has sealed the INF agreement's fate.

But there is a strong sentiment in both the Pentagon and White House that the agreement is out of date. US officials point to China's huge arsenal of intermediate-range nuclear missiles, which it has been able to develop unconstrained by any treaty. In this light, the US sees the INF deal as a brake on its own strategic capabilities in the Asia-Pacific region.

Perhaps the Europeans who are most alarmed (and most at risk) by the deployment of new Russian missiles can bring their weight to bear. But if both Washington and Moscow see good reasons for abandoning the treaty, then the other Nato countries are unlikely to pull a renewed INF agreement out of the hat.

Should it be saved?

During the Cold War years, arms control and disarmament agreements played a vital role, and not just in reducing the numbers of nuclear missiles and maintaining stability. They were the central element in the East-West dialogue. This was the domain where Washington and Moscow met across the table as equals.

Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan sign the INF treaty in December 1987

It continued after the Cold War with the new START treaty, signed during the Obama administration, setting limits on long-range strategic missiles.

If the INF Treaty unravels, then many experts fear for the future of the new START agreement, which expires in February 2021, unless the two parties agree to extend it. Will they even want to, given the state of their relations?

This is the paradox of arms control. Such agreements maybe don't matter so much in times of peace and stability; but when tensions mount they really do.

Shifting global power

The likely demise of the INF Treaty and the fate of the broader arms control edifice it represents is also a sign of the dramatic shift under way in world affairs.

The US concern about China points to this. Maybe the era of bilateral arms control, involving just Washington and Moscow, is coming to an end. China is now a significant nuclear player. Some 10 other countries beyond the US and Russia have fielded intermediate-range nuclear missiles.

The contrary view asserts that yes, the "bilateral era" is ending, but Russia and the US still have by far the largest strategic arsenals and that controlling these remains a good thing in itself. It also sets a benchmark for disarmament which should be extended to include other countries.

But with relations between Russia and the West at a low ebb, with a US president asserting the credo of "America First" and with Russia pursuing its own assertive foreign policy, it is hard to see the INF Treaty or even new START surviving.

Worse, it is hard to see US-Russian relations improving any time soon. The fact that their competition is now only one aspect of a multi-polar battle for strategic and economic dominance makes a world without arms control both more likely and more dangerous.

- Published1 February 2019

- Published26 October 2018

- Published5 December 2018

- Published24 October 2018

- Published4 December 2018

- Published24 October 2018

- Published22 October 2018