How is Dublin preparing for a possible no-deal Brexit?

- Published

Standing on top of the roof of the Dublin Port Company's headquarters, you can see lots of building work amidst all the docked ships at the River Liffey's mouth.

And while that construction is not entirely Brexit-related, management at the port says it has to be prepared for the possibility of a no-deal and any potential economic fallout.

The UK is scheduled to leave the EU on 29 March, whether or not there is a negotiated deal.

British Prime Minister Theresa May is hoping that her draft Withdrawal Agreement will get through the House of Commons, but preparations are under way in case it does not.

There is agreement across Irish society that Brexit will have an adverse effect on the country, but the worst scenario as far as the Irish government is concerned is that the UK leaves without a negotiated settlement.

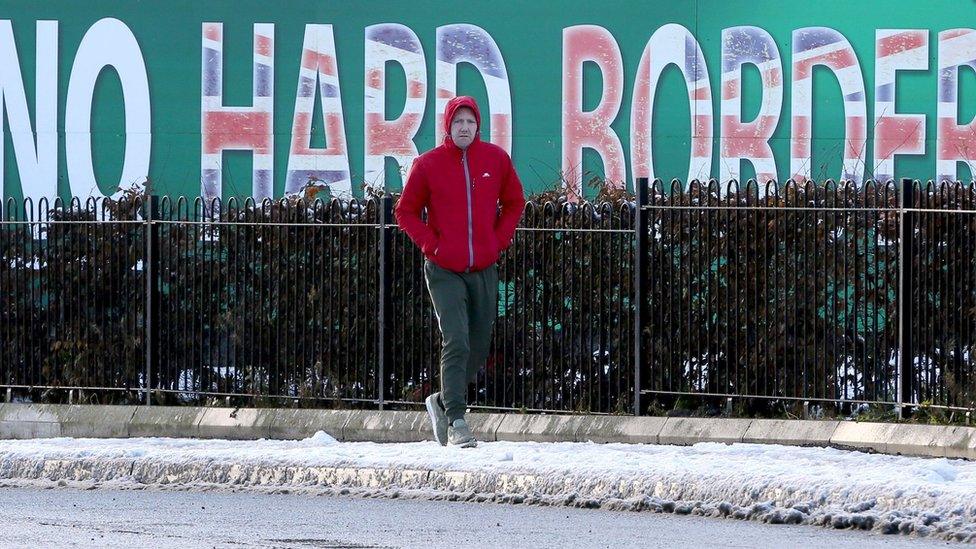

Politicians here refer to that option as a "hard" Brexit.

The International Monetary Fund forecasts that Ireland's economic growth would take a 4% hit "in the long run" if there is a "cliff-edge" break with the EU, because of the highly integrated nature of the Irish and UK economies.

And the independent Dublin-based think tank The Economic and Social Research Institute estimates that a "hard" Brexit could cost households up to €1,400 (£1,260) a year,, external because of a potential increase in food prices and possible trade tariffs.

The Irish government set out its approach to dealing with a no-deal Brexit in December

Despite no-one in authority being in a position to predict how Brexit will unfold, the Irish government has already announced plans for an extra 1,000 customs and veterinary staff to work at Dublin and Rosslare ports and at airports, as well as new money to train people in sectors likely to be badly affected.

It has organised a series of very well-attended roadshows around the country with the involvement of state agencies with the theme "Getting Ireland Brexit Ready", external for every Brexit scenario.

And there is evidence that more companies - worried about possible delays and resulting costs at Dover - are forsaking the UK land-bridge for new "Brexit-busting" super-ferries that would sail directly between Dublin and Zeebrugge and Rotterdam, bypassing uncertainty in Britain.

It is too early to say what impact they are having, but the development is seen as significant.

There is an Irish political and economic consensus on Brexit.

For political reasons there is widespread agreement that there has to be a so-called "backstop" unless and until there is a wider trade agreement to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland.

It is feared that such a border could risk a return to violence after a hard-won peace.

Parts of the Conservative Party and the DUP as a whole strongly oppose the backstop, believing it risks weakening the union between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

They also feel it may effectively trap the UK in a customs arrangement with the EU, preventing it from making its own trade deals with non-EU states.

There is also a consensus in Dublin that for economic reasons, the Republic of Ireland wants as close a relationship with the UK as possible for the sake of jobs and mutual prosperity after the UK leaves the EU.

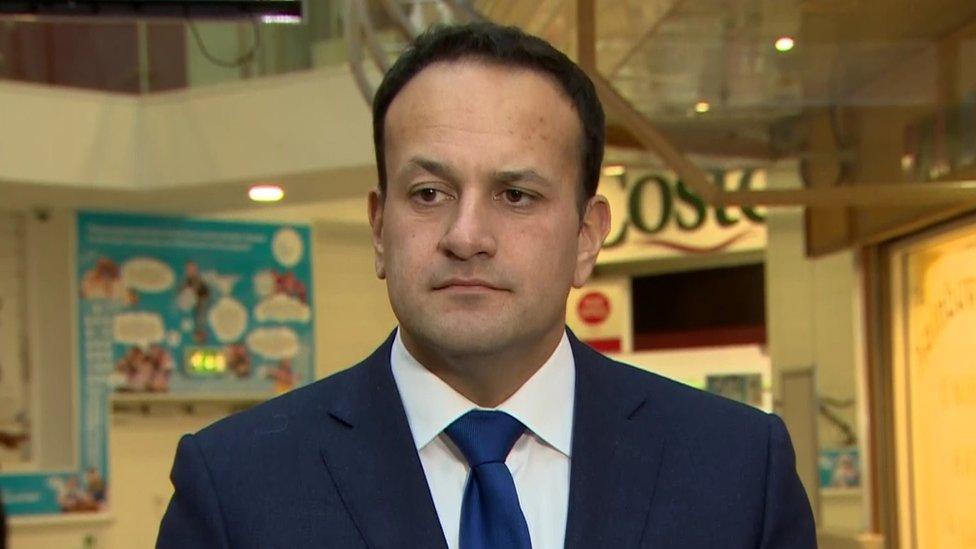

And yet, despite that consensus, the opposition parties in the Dáil (parliament), Fianna Fáil and Sinn Féin, have frequently criticised Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Leo Varadkar's Fine Gael government for not doing enough to prepare for the no-deal scenario.

There has also been an often unspoken fear that the EU might, at the last moment, try to force Ireland to relent on the backstop to allow Mrs May to get her deal to pass in Westminster.

That concern is largely based on what happened during the financial crisis, when Dublin came under enormous pressure to apply for a bailout to protect its banks.

But Irish government ministers insist that the remaining EU27 countries are at one on the issue.

European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker, the EU's chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier, and the president of the European Council, Donald Tusk, have been frequent visitors to Dublin, expressing solidarity with their Irish counterparts.

German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas reiterated that support at this week's Global Ireland conference in Dublin, appearing alongside Irish Foreign Minister Simon Coveney.

Simon Coveney (l) and Heiko Maas (r) both emphasised the importance of avoiding a hard border

While a no-deal Brexit is most definitely seen by many as a threat to the Irish state, it also offers opportunities.

The Industrial Development Authority, which is responsible for attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the country, notes that more than 55 companies have moved at least part of their operations from London to the Irish capital because of Brexit.

Those companies include Bank of America, Barclays, Citigroup and Morgan Stanley, helping to make 2018 a record year for FDI job creation.

There is a fear, though, that domestic companies - which tend to have a closer economic relationship with the UK than the multinationals - could suffer with resulting job losses, especially if the pound falls as a result of a failure to agree a deal.

That would make Irish exports less competitive and British imports cheaper, raising the prospect of some companies lobbying for possible state support.

Amid all the confusion and uncertainty about Brexit, the Irish government has consistently said that it thinks it more likely than not that a no-deal Brexit will be avoided, but stresses it necessarily has to plan for all eventualities.

Management at Dublin Port is taking the politicians at their word, and getting ready for a no-deal Brexit scenario, preparing to house more customs officials and veterinary inspection staff.

It seems certain that the cranes, trucks and construction staff at the mouth of the Liffey will be busy for some time to come.

- Published13 December 2018

- Published29 November 2017

- Published26 October 2018

- Published19 October 2018

- Published19 July 2018