Why Erdogan's big Turkish ambitions could come tumbling down

- Published

For the past 16 years President Erdogan has championed construction projects as an engine for Turkish growth

The crater is the size of a football pitch, dug 50m (165ft) deep into the earth. Mounds of rock line the surface. The only life here is the seagulls drinking from pools of stagnant water.

It was supposed to be the site of Istanbul's gleaming new development: a grandiose mix of apartments, malls and spas in the district of Fikirtepe.

The promotional video from 2010 showed a symbol of Turkey's newfound wealth.

The homes of at least 15,000 people were demolished to make way for it. Many paid deposits to buy into the project.

But as financial problems hit, investors pulled out – and most of the planned buildings never materialised.

All that's left is a gaping hole of bankrupt companies and broken promises.

It is symptomatic of a wider economic slump that poses the gravest threat to Recep Tayyip Erdogan in his 16 years in power.

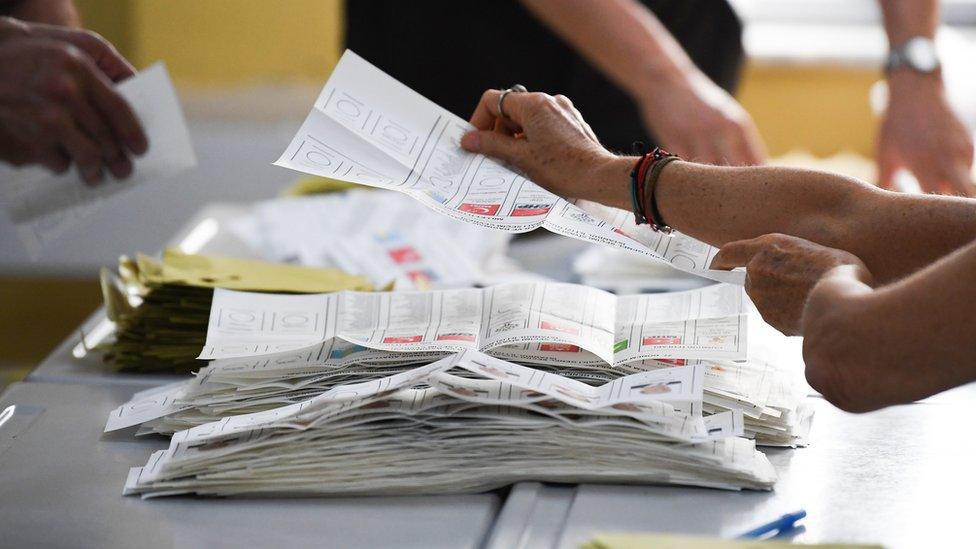

Polls before this weekend's local elections suggest his governing AK Party could lose control of the capital, Ankara – and perhaps even Istanbul.

'I feel hatred towards him'

Zeynep Duzgunoldu, aged 60, welled up with tears as she pointed to where her old home used to stand beside a fresh fig tree.

The government is ruthless. They promise to pay our rents - and then forget about us after elections. We're cheated"

"People used to call it 'the house with the beautiful kitchen'", she said, her voice cracking. "Now my rucksack is my home. I'm ashamed to ask my children for money."

Firdevs Uluocak's house is on the edge of the failed construction site and was destabilised by the digging.

There's one target for her anger: Turkey's builder-in-chief, President Erdogan.

Firdevs Uluocak feels personal anger towards the president

"I feel hatred towards him", she said. "I always voted for him - but he's ruined his people."

Over the past 16 years, Mr Erdogan has championed construction as the engine of Turkey's growth.

His so-called "mega projects" - from airports to bridges to tunnels - have transformed the country's infrastructure.

And high-rise housing developments have changed city skylines, often to the horror of architects.

One of President Erdogan's recent successes was the opening of Istanbul's new airport in October 2018

Construction moguls close to the president have won state tenders through political support.

The industry is mired in claims of corruption and cronyism.

But with inflation now at 20% and the Turkish lira having plunged by around a third, the cost of importing raw materials and servicing foreign loans has soared - and construction companies are failing.

Pana Yapi, the conglomerate running the Fikirtepe project, told the BBC "the whole country is going through an economic crisis", arguing that it too is a victim.

Cranes suspended in mid-air and half-built skyscrapers that now dot Istanbul are a sign of that crisis.

Turkey entered recession last year, shrinking 3% in the final quarter. Many fear there is worse to come.

"Turkey is heavily dependent on foreign-denominated debt and when that's harder to service, that's when you see the problems we're in", said Can Selcuki, general manager at Istanbul Economics Research.

Economist Can Selcuki thinks Turkey needs an injection of foreign capital

"We could be on the brink of a major crash. We need high sums of foreign cash", he said, "and the most likely address for that is the International Monetary Fund".

President Erdogan has argued vociferously against an IMF loan, which would come with stringent conditions.

"But the cost of not finding the capital," argued Mr Selcuki, "might be increased bankruptcies and a downward spiral."

Could slump bring down Erdogan?

The economic downturn has prompted the president to turn the argument towards other issues.

He has shown the video of the New Zealand mosque attack in rallies to galvanise his conservative, pious voters, whom he needs to turn out.

As a quick fix for the cost of food – which has soared by a third – the government has bought up vegetables from farmers. It sells them directly to consumers in public stalls, bypassing the middle-men who have inflated prices and whom the president labels "food terrorists".

At one of these stalls in the Istanbul district of Aksaray, lines were long as people waited to buy tomatoes, aubergines and spinach at half the price of supermarkets.

Vegetable stalls like this are seen by some as an electoral ploy

"The queues aren't a sign of poverty but of opportunity," said shopper Omer Cakirca, lauding the project. "Everywhere is like this. If there is something on sale, everyone will go there."

But Esref Korkmaz disagrees: "I bought cucumbers and tomatoes today - but this is just an investment for the elections," he said. "They won't remain after April. I voted for the AKP before but not again because the economic situation is bad. I'll hold my nose and back the opposition this time."

The economy propelled Recep Tayyip Erdogan to power.

It could now be his undoing.

- Published20 March 2019

- Published10 July 2018

- Published21 January 2019