Pedro Sánchez: The rise of Spain's battle-scarred PM

- Published

Pedro Sánchez stressed that dialogue was the only way to resolve the Catalan crisis

The vote securing the prime minister's job for Pedro Sánchez was characteristically razor-thin, for a Spanish socialist known for risk-taking and ups-and-downs.

Tricky negotiations with far-left Podemos, then with Catalan and Basque nationalists, did just enough to get Mr Sánchez over the line on 7 January: he won a confidence vote in parliament by 167 votes to 165.

He will lead Spain's first coalition government - alongside Podemos - since democracy was restored in 1978, after the long Franco dictatorship.

Yet it remains a minority government, so it will have to battle hard to get new laws passed.

He lamented the "toxic atmosphere" in Spanish politics, telling MPs he would strive for dialogue, human rights and social justice.

In speeches before the vote he faced anger from centre-right and far-right leaders, who castigated him for doing political deals with the Catalans and Basques, and questioned his commitment to fighting terrorism.

Mr Sánchez heads into a coalition with Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias

He has ambitious plans to raise the income tax level for the highest-paid Spaniards and roll back labour market reforms, dating from the previous conservative government, which made it easier to fire workers.

Academic achiever

He studied economics at Madrid's Complutense University, graduating in 1995, then completed two postgraduate courses, earning a Master's degree in EU economics from the Free University of Brussels.

Later he lectured in economics in Spain and had a spell working for the UN High Representative in Bosnia-Herzegovina. He is married and has two teenage daughters.

Born in 1972, he grew up in a well-to-do Madrid family, the son of an entrepreneur father and civil servant mother. He played in a student basketball team and is also a keen runner.

In early 2018 he was lagging in the polls as the leader of Spain's opposition, bruised by two resounding electoral defeats.

But he seized the opportunity in May 2018 to snatch power away from conservative Popular Party (PP) leader Mariano Rajoy, who was hit by a huge political funding scandal.

Mr Rajoy was ousted in a no-confidence vote - a first for Spain's post-Franco democratic era.

Then last April Mr Sánchez secured the first election victory for his Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) since 2008.

A keen runner, Mr Sánchez took part in a race near Barcelona in April 2017

His political honeymoon did not last long - the PSOE did not get a majority and in November Spain's voters went back to the polls after Catalan nationalist MPs withdrew support.

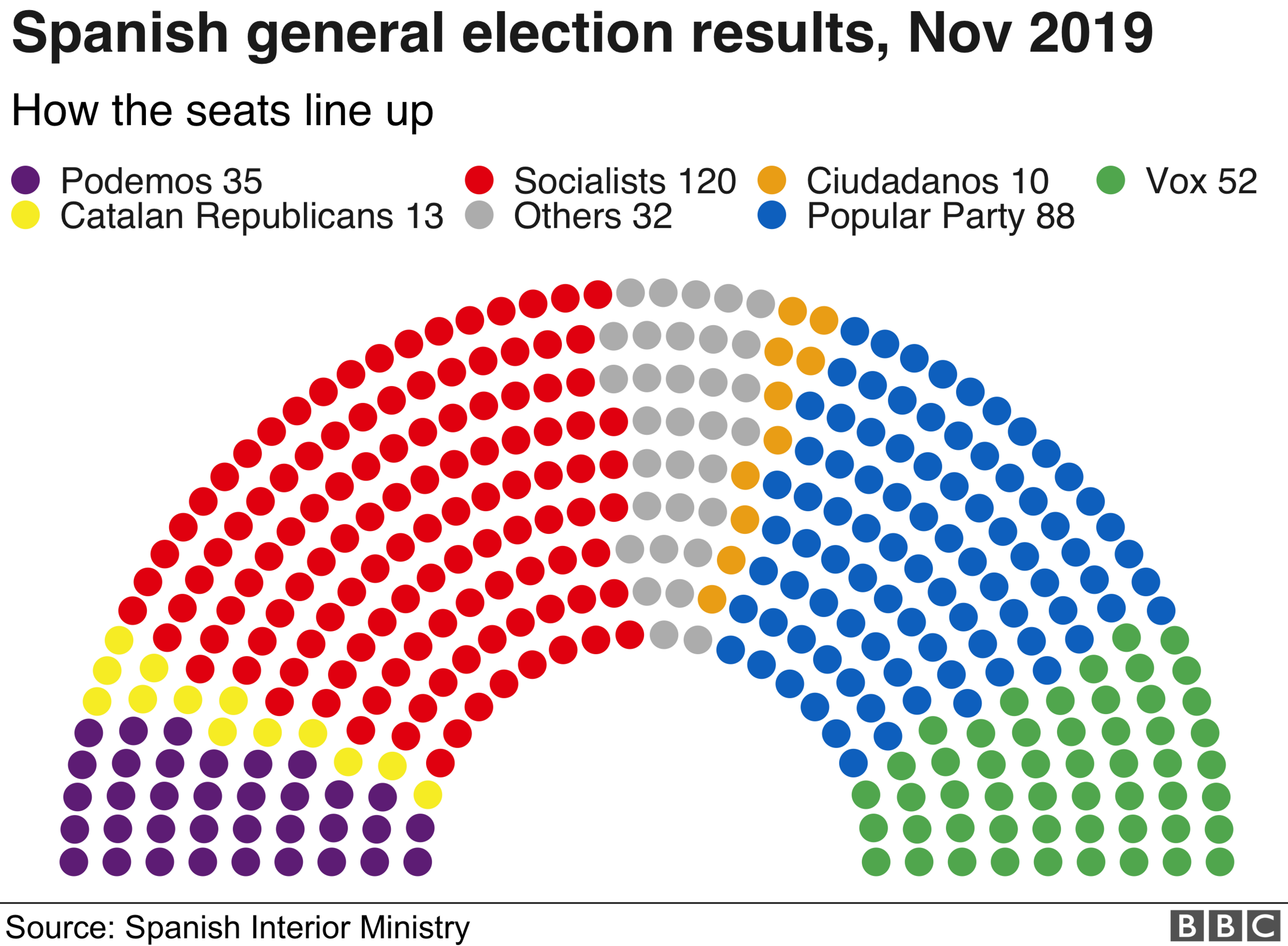

The wheeling and dealing was not over for him, however, as the PSOE came top but weakened, with three fewer seats than in April.

Again, the long-running Catalonia crisis influenced Madrid politics: key to Mr Sánchez's narrow victory in parliament was the agreement of the biggest Catalan separatist party, the ERC, to abstain.

"He has used his time in government to project an image of gravity and of being someone who is suited to the post of prime minister," says Josep Lobera, a sociologist at Madrid's Autonomous University (UAM) – who adds that being in government has boosted Mr Sánchez's standing among leftist voters.

"Regardless of whether or not he's actually managed the country effectively, he's projected that image."

After lagging behind the PP in polls when in opposition, the PSOE shot ahead in the wake of Mr Sánchez's arrival in office in 2018.

Mr Sánchez, 47, adopted eye-catching measures that appealed to his base, such as raising the minimum wage, appointing a female-dominated cabinet, and taking in the Aquarius migrant vessel after Italy had shunned it.

In October 2019 he also fulfilled a pledge to exhume the remains of the dictator Francisco Franco from his mausoleum and rebury them somewhere less divisive.

A battle for every change

By Mr Sánchez's own admission, it has been difficult for him to take on more ambitious, structural reforms, with his party short of a majority in parliament.

Plans to overhaul the education system, legalise euthanasia, change labour regulations and shake up national broadcaster RTVE were all put on hold.

But the PSOE profited from the struggles of some rival parties.

Ciudadanos, which once competed with the PSOE for the centre ground, moved to the right. But it did poorly in November, when the new far-right Vox party surged into third place.

Podemos, the Socialists' main rival on the left, has been riven by infighting. Many former Podemos voters turned to the PSOE.

All this added to Mr Sánchez's reputation as a survivor. In 2016, in a previous stint as Socialist leader, he was ousted from the post following a bitter conflict within the party.

Defying the party's old guard, he successfully ran in the 2017 primary, becoming Socialist leader for a second time.

Catalan discontent

The Catalan independence drive has overshadowed his time as prime minister.

His administration has engaged with the pro-independence government, restored a bilateral working group, and allowed jailed Catalan politicians to be moved from Madrid to prisons in their home region.

Mr Sánchez has also held meetings with Catalan president Quim Torra.

Such moves prompted PP leader Pablo Casado to call Mr Sánchez "the biggest villain in Spain's democratic history", casting him as an opportunist who was willing to negotiate the independence of Catalonia in exchange for parliamentary support.

Catalonia could yet make or break the career of Mr Sánchez.

- Published7 January 2020

- Published11 November 2019

- Published14 October 2019

- Published21 August 2023