Franco exhumation: Spanish dictator's remains moved

- Published

Franco's coffin was carried out of the mausoleum

The remains of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco have been moved from a vast mausoleum to a low-key grave, 44 years after his elaborate funeral.

Thursday's long-awaited relocation fulfils a key pledge of the socialist government, which said Spain should not continue to glorify a fascist who ruled the country for nearly four decades.

His family unsuccessfully challenged the reburial in the courts.

The Franco era continues to haunt Spain, now a vibrant democracy.

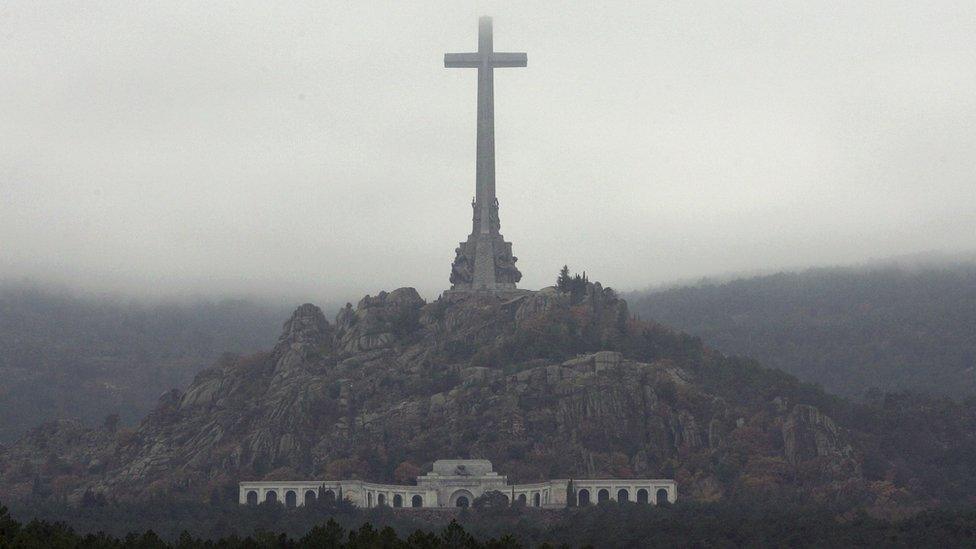

After the remains were exhumed in a private ceremony, family members carried the coffin out of the basilica of the Valley of the Fallen, a national monument carved into a mountain about 50km (30 miles) from Madrid.

Franco's remains were then loaded on to a helicopter and taken to a private family vault at a cemetery in Madrid, where they were re-buried next to his late wife.

In a television address on Thursday, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez said the exhumation was a step towards reconciliation, adding: "Modern Spain is the product of forgiveness, but it can't be the product of forgetfulness."

WATCH: Why Spain wants to exhume Franco's remains

Only a few people were allowed to attend the event, which took place under high security. They included the justice minister, an expert in forensics, a priest and 22 descendants of Francisco Franco. Media were excluded but more than 200 journalists were near the site.

A crane was needed to lift a concrete slab weighing 1,500kg that covered the coffin. In total, the exhumation and re-burial will cost about €63,000 (£54,000; $70,000).

Why is Franco being moved?

The Valley of the Fallen houses more than 30,000 dead from both sides of the 1936-39 Spanish Civil War, in which Franco's Nationalist forces defeated the Republican government.

It was partly built by political prisoners, whom Franco's regime subjected to forced labour.

Thousands of those killed by his forces were interred there without their families' consent.

The Valley of the Fallen is a shrine for the far-right

The site has been a focal point for Franco supporters and a shrine for the far right. Visitors were able to lay flowers and say prayers at the late dictator's tomb.

Prime Minister Sanchez said on Thursday the site would symbolise something different when it reopens in a few days' time, and that only victims of the civil war now lie interred there.

Visitors could lay flowers and pray at Franco's tomb

Franco was moved to the El Pardo cemetery, where various other politicians are interred. The family were not allowed to drape the national flag on his coffin but took along the same flag that covered Franco's coffin at his 1975 funeral.

Do Spanish people support this?

The burial place of Franco has been the subject of fierce debate for decades and Spaniards remain divided over whether his remains should have been moved, newspaper polls suggest.

An El Mundo poll this month said 43% supported the move, with 32.5% against and the rest undecided.

Franco supporters gathered outside the El Pardo cemetery where he was re-buried

Many descendants of Franco's victims are happy that action is finally being taken.

"The idea that people who were killed by Franco's troops are buried together with Franco, it's very absurd, and they're still glorifying him as if he were the saviour of Spain," Silvia Navarro, whose great uncle died in 1936, told the BBC.

But critics have accused the government of playing politics ahead of an election next month.

About 100 Franco supporters gathered outside the El Pardo cemetery on Thursday to protest the exhumation.

What's the Franco family's view?

Franco's grandson, Francisco Franco y Martinez-Bordiu, said he was furious with the government.

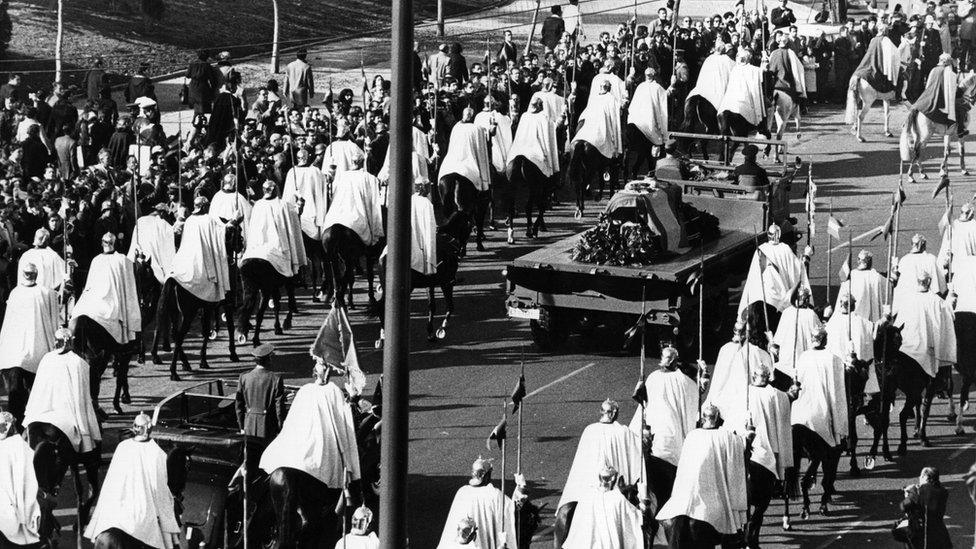

Franco's funeral was held on 23 November 1975

"I feel a great deal of rage because [the government] has used something as cowardly as digging up a corpse as propaganda, and political publicity to win a handful of votes before an election," he told Reuters news agency.

Last month, the Supreme Court rejected an appeal by Franco's family against the exhumation. It also dismissed a proposal for an alternative site.

The family, who did not want him moved at all, preferred for him to lie in a family crypt in the Almudena Cathedral - in the centre of the capital.

Grandson Francis Franco (right) carried a flag as the family arrived at the Valley of the Fallen memorial

But the government argued that the former dictator should not be placed anywhere where he could be glorified. It also said there were potential security issues with the cathedral site.

How has Spain dealt with the Franco era?

Unlike in Mussolini's Italy and Nazi Germany, defeated in World War Two, Spain's transition to democracy in 1975 was more gradual.

Though democracy is well established now, many believe the country has never faced up to its fascist past. There was an unwritten "pact of forgetting" during the transition.

An Amnesty Law adopted in 1977 prevents any criminal investigation into the Franco years. Statues of Franco were removed and many streets were renamed.

A Historical Memory Law, passed in 2007 by the socialist government at the time, recognised the war victims on both sides and provided some help for surviving victims of Franco's dictatorship and their families.

But the work to locate and rebury thousands of civil war dead has been slow and controversial.

More than 100,000 victims of the conflict, and the ferocious repression carried out afterwards, are still missing.

Francisco Franco, 1892-1975

Born in Galicia to a military family, became the youngest general in Spain in the 1920s

Following the election of the leftist Popular Front in 1936, Franco and other generals launched a revolt, which sparked a three-year civil war

Helped by Nazi Germany and Mussolini's Italy, Franco won the war in 1939 and established a dictatorship, proclaiming himself head of state - "El Caudillo"

Franco kept a tight grip on power until his death in 1975, after which Spain made a transition to democracy

- Published24 September 2019

- Published24 August 2018

- Published15 July 2018

- Published23 April 2018

- Published15 February 2016

- Published12 March 2018

- Published17 July 2016

- Published19 July 2011

- Published28 June 2011